In the 1980s, around the time we graduated from college, a roommate of mine received a jury-duty summons, to which he insouciantly said he wouldn’t respond. I undertook a prank, photocopying the court system’s letterhead onto blank paper, on which I then typed an ominous letter demanding his presence, and mailed that to him. He thought it was real, until he got to the paragraph telling him to bring a toothbrush and extra clothing. The fake document was funny, and undoubtedly illegal.

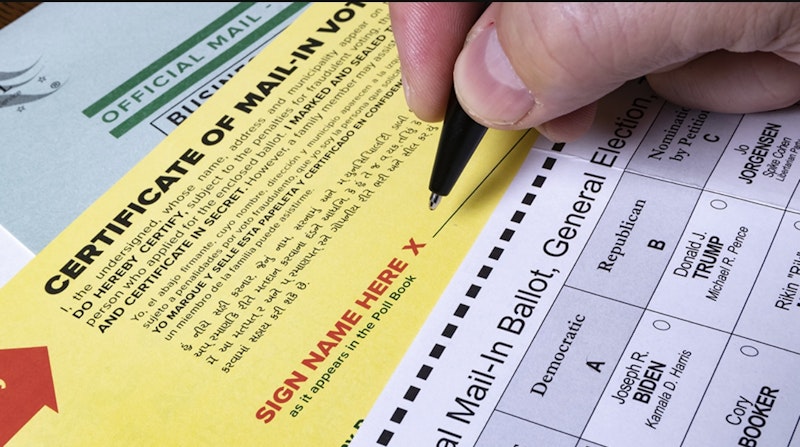

That joke came to mind as I contemplated authenticity and its lack in current-day political controversies, including what the National Archives politely calls “unofficial Certificates of Ascertainment and Vote (“Certificates”) received by the Office of the Federal Register in connection with the 2020 presidential election, not accepted as evidence of official State action, including unofficial Certificates submitted by alternate electors.” That is, these were fake papers presented by fake electors seeking to show that Donald Trump had won electoral votes he hadn’t won.

The “alternate” electoral certificates were as phony as my prank letter, but Republican reverence for the rule of law has weakened dramatically, and not just among Trump supporters. I recently watched a debate audience howl when Chris Christie said we should stop normalizing the conduct Trump showed in seeking to reverse the 2020 election result. And Nikki Haley—in whom I occasionally think I see signs of greatness, despite my many disappointments—raised her hand to affirm that she’d support Trump if he’s the nominee and convicted of criminal charges. As for Christie, he said he’d order U.S. Attorneys to prosecute street crime in troubled cities, though that step has no evident basis in federal law.

Providing valid documents has been a focus of mine lately. I’ve started on paperwork to apply, for myself and my son, for citizenship of Austria, based on my father’s persecution there in the Nazi era. The process requires providing what documents you can about the persecuted ancestor; if you have an ancestor’s Opferausweis, a postwar “victim card,” that’s a particularly strong support. You also must document your identity and connection to the victim; that includes getting my and my son’s birth certificates “apostilled,” or authenticated for international use, by city and state authorities. As a criminal or terrorist background would be disqualifying in my dual-citizenship effort, I’m also required to get an FBI background check, including a fingerprint check, and the resulting report will needa federal apostille.

As a copyeditor and fact-checker, I’ve an eye for detail, though this is much more evident in dealing with things on paper or a screen than in the physical world. Once, in the early-1990s, I was supposed to meet my uncle at his Manhattan apartment and, having a key, let myself in to wait for him. His future second-wife was a pianist, and some of her possessions had been placed in the apartment. I read magazines for a couple of hours in the living room, and then my uncle arrived and said, “What do you think?” My reply was, “About what?” There was a baby-grand piano a few feet from me, but I hadn’t noticed it.

We all have shortfalls in assessing or recognizing reality. Still, I’m struck that a large majority in the Republican Party—about 70 percent, according to polls—believe the 2020 presidential election was stolen, a view that’s survived not only dozens of court cases in which it was rejected (including by Republican and Trump-appointed jurists), and its disavowal by the Attorney General and the White House Counsel during the Trump administration, but also evidence, in recordings of Steve Bannonand Roger Stone, that a scheme to “stop the steal” was in the works before the election happened.

Back in the early-1980s, I found a dubious role model in Watergate felon G. Gordon Liddy, whose tough-guy persona struck a chord with my adolescent aspirations. Among his talents was a knack for phony credentials. As he boasted in his autobiography Will, he used his position as a political appointee at the Treasury Department to create an impressive-looking badge—meant for use by undercover CIA officers—that he could flash if anyone asked whether he had a permit to carry a gun.

On a recent flight back from Italy, I watched White House Plumbers, an absorbing comedic take on Watergate. In one memorable scene, Liddy and E. Howard Hunt present proposalsfor various covert—and illegal—operations to Attorney General John Mitchell, using posters and an easel. In real life, as recounted by Garrett Graff, author of Watergate: A New History, an aide’s recollection of that easel, borrowed by Liddy from co-workers at a Nixon campaign office, ended up implicating the Attorney General and showing that high levels of the Nixon administration were involved in dirty tricks.

—Kenneth Silber is author of In DeWitt’s Footsteps: Seeing History on the Erie Canal, and posts at Post.News.