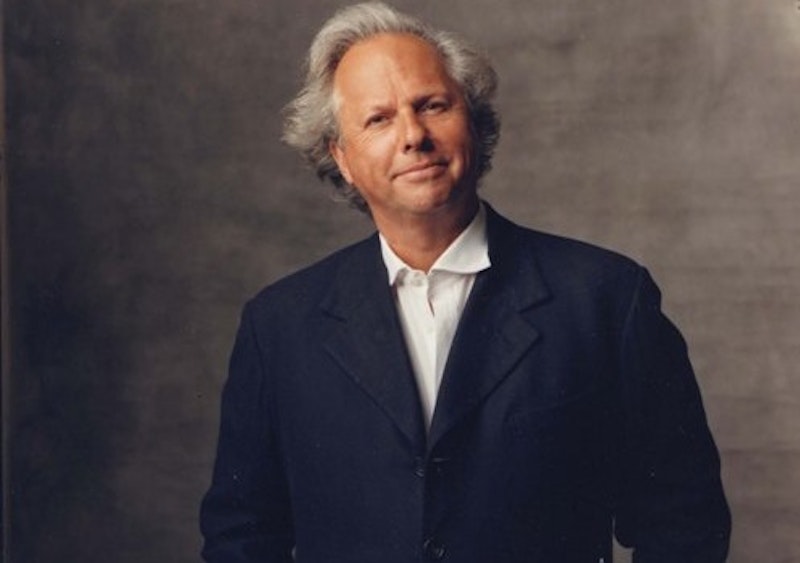

I’ve met and conversed with Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter many times over the years—in 1987, for example, when his Spy magazine was the toast of Manhattan, he was kind enough to buy me lunch and offer suggestions on my then-embryonic plans to launch a competitor to the Village Voice—and think he’s a grand fellow. Once, at a book party sponsored by VF for a writer who shall remain nameless, Carter whispered in my ear, “My God, isn’t he a bore! Let’s go somewhere and have a smoke.”

Nevertheless, Carter deserves a trip to the woodshed for his wacky, almost nonsensical, Editor’s Letter in July’s issue of his magazine, headlined “The Paper Chase.” The column begins on solid ground, rebuking all the chin-scratching and moaning in daily newspapers today about the print industry’s dismal condition, as if readers (those that are left, at least) don’t have problems aplenty themselves in maneuvering through this protracted and vicious recession. Carter says, “It’s no wonder readership is down,” which is hyperbole, of course, but his complaint is, I suppose, plausible.

The bulk of Carter’s words are devoted to praising London’s excellent broadsheet The Telegraph for its triumphant investigative series of stories about the expense report scandal in Britain’s Parliament, which has rocked that institution. Prime Minister Gordon Brown, the Labour Party’s dead duck, must’ve considered moving to the Congo after The Telegraph’s cataloguing of financial malfeasance dominated the news this spring. So, the longtime VF editor and gossip-magnet is on the mark there, too.

But it’s the window-dressing and conclusions that Carter draws from The Telegraph’s success that are, if not necessarily daft, amazingly out of touch. In a pro forma remark, Carter repeats the mantra that the “health and vigor” of newspapers is vital to the country’s well-being, if only to keep “a watchful eye on corrupt politicians and venal corporate overlords.” I’m sure that the dwindling number of employees at the Tribune Co., publisher of The Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune and Baltimore Sun, among other properties, would nod heartily at Carter’s “venal corporate overlords” dig, if they weren’t too busy looking for work elsewhere to read Vanity Fair.

And this doozy: “I would also hope you feel that the loss or even weakening of the nation’s principal daily, The New York Times, would mark an end to life as we know it.” I’ve read the Times every day for most of my life—starting at the age of seven or so—but in the past year that frequency has diminished dramatically, and frankly, I’m no worse for wear, let alone having a life-altering experience. Carter says that “youthing” down a serious daily to attract young readers isn’t the answer, and that’s certainly true. However, when he writes that, “[T]he only way you’re ever going to get the average 21-year-old to read a daily newspaper is to wait 9 years until he’s 30,” it’s clear that Carter is living in an isolated world. Put simply, if someone isn’t reading a daily at 21, he or she sure won’t develop the habit at 30; let alone the brutal fact that in 2018 daily newspapers, those that are left, will be niche, rather than mass, products.

Carter believes that dailies can solve their problems by emulating The Telegraph’s exhaustive, expensive and time-consuming investigation of the political scandal that paper uncovered. Unfortunately, at least for the media, such an explosive story can’t be conjured up with the wave of a wand: in the United States, at least, explosive stories such as Watergate, Iran-Contra and Enron, are notable exceptions to the routine reporting of day-to-day activities in the world, nation or local community.

But Carter, who doesn’t once mention that glossy magazines, including those in the Conde Nast stable that includes VF, are no longer minting money, is undeterred in dispensing pointers to beleaguered reporters and publishers. His go-get-‘em guys! slap on the back: “My suggestion to newspapers everywhere is to give the public a reason to read them again. So here’s an idea: get on a big story with widespread public appeal, devote your best resources to it, say a quiet prayer, and swing for the fences.”

It could be that Carter himself doesn’t read, whether out of self-denial or indifference, the volume of stories about the demise of print media, for if he did, he’d know that the “fences” have been moved about a mile further, and no amount of praying will ever bring them closer.

Graydon Carter's Fantasy World

Vanity Fair’s editor tells daily newspapers to stop bitching and get back to work.