War is hell on the military’s health, but not always because of guns and explosives. Ever since the first American troops went to battle in World War I, the federal government and tobacco industry have been in cahoots to create new generations of smokers. And now government is trying to undo the damage by forcing cigarette companies to run $30 million in cautionary ads to scare people into quitting the sot weed.

Whatever the level of government, and how much contrition, government wants to thank you for smoking. The tobacco industry has always been a huge profit center for government and continues to produce revenue even though it has forced paybacks through massive lawsuits and penalties. The partnership continues.

You’ve seen it on television and in films, so it must be true: The first items surviving soldiers were handed during World War II on returning from the front lines were a cup of coffee and a pack of cigarettes, dubious pacifiers for living through the shell-shock of grenade and mortar fire. And since then, tobacco companies have prospered, and an entire generation of plaintiffs’ lawyers enriched by suing them in return.

Oncologists who treat chest-related cancers say that smoking and its related illnesses spike during wartime, though many diseases don’t appear until decades later. And there’s no question that government has been an enabler. Anyone who wants to witness addiction first hand should visit a cancer treatment center and see a patient hurry to light up a smoke after three hours of radiation and chemo.

At the onset of the Korean War, for example, Navy recruits at boot camps were entertained regularly at Saturday night “smokers” where they were presented with free cartons of cigarettes and Zippo lighters. Cigarettes were available at PXs—discount and tax-free Post Exchange stores on shore and aboard ships—at 70 cents a carton. Many who entered the military as non-smokers were soon hooked, mainly through peer pressure, complete boredom or the studly look of a man in uniform wrapped in a nimbus of smoke.

But the practice actually began during World War I, when cigarette manufacturers started targeting military personnel by going so far, with government cooperation, as including cigarettes with the troops’ rations. During the war in Vietnam, the smoking of marijuana was an addictive recreational pastime as well as a mind-numbing diversion from the horrors of jungle warfare. Cigarette companies still distribute free cigarettes to troops who are deployed to such outposts as Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia.

Studies show that most people who begin smoking while in the military become lifelong smokers and cost the government billions in health care spending. The Veterans’ Administration is now experimenting with marijuana as an antidote to post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to combat the high suicide rate, trading one illness for the prospect of another.

And as if the left hand is oblivious to the motions of the right, the Food and Drug Administration has created a special in-house committee to make certain that effective smoking cessation anodynes receive speedy treatment through the FDA’s testing and approval process.

During the 1950s and 60s, civilians got the partnership’s come-on treatment, too. Every airline meal tray included a sample pack of four or five cigarettes on the government-regulated carriers. And cigarette manufacturers’ representatives distributed sample packs of their products on street corners in major cities, allowed by government, of course. Today, smoking is strictly déclassé, defined by underclass education and economics.

Fifty years ago, 42.4 percent of Americans smoked. In 2014, the latest figures posted, that number was down to 17.8 percent and dropping—mainly because of anti-smoking laws, focus on educating young people, loss of glamour and high taxes, which boost the cost of a pack of cigarettes to well beyond $6 in many states. Tobacco taxes are both a health aid and a revenue raiser but they’re paid disproportionately by the poor as the social group most likely to smoke.

The nation’s average state tax per package of cigarettes is $1.72. New York has the highest per pack state tax at $4.35, while the lowest is Virginia at 30 cents. Maryland’s $2 a pack is 15th among the 50 states. It could be argued that taxes on tobacco are a diminishing return because as consumption declines so does revenue. But to compensate, states continue to raise taxes, in a competing roundelay of loss and gain.

In 2014, the states collected $17 billion from cigarette taxes, while the federal government collected $13 billion. High tobacco taxes have also spawned a thriving underground culture of cigarette smuggling. It’s estimated, for example, that 50 percent of the cigarettes in New York are smuggled from another location. Maryland’s stretch of I-95 is a frequent stop-and-search trap for cigarette smugglers.

Here is the text of the full-page advertisement that appeared in selected newspapers, more of a negotiated declaration than a mea culpa:

“A Federal Court has ordered R.J. Reynolds Tobacco, Philip Morris USA, Altria, and Lorillard to make this statement about the health effects of smoking.

“Smoking kills, on average, 1,200 Americans. Every day.

“More people die every year from smoking than from murder, AIDS, suicide, drugs, car crashes, and alcohol, combined.

“Smoking causes heart disease, emphysema, acute myeloid leukemia, and cancer of the mouth, esophagus, larynx, lung, stomach, kidney, bladder, and pancreas.

“Smoking also causes reduced fertility, low birth weight in newborns, and cancer of the cervix.”

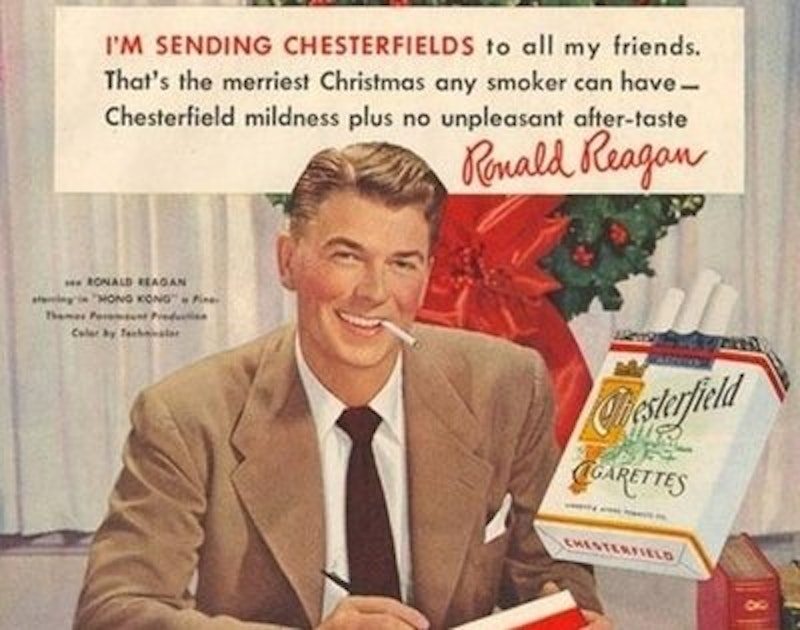

By comparison, here’s a sampling of the texts from cigarette advertisements from the 1950s-1960s, demonstrating innocence or naivete long before the anti-smoking crusade began:

Lucky Strike—“20,679 physicians say Luckies are less irritating.”

Pall Mall—“Guard against throat scratch”

Camels—“Rosalind Russell [a film and TV star of the era] says L&M Filters are just what the doctor ordered”

Lucky Strike—“There’s never a rough puff in a Lucky”

Camels—“More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette”

Marlboro—[A photo of an adorable baby in a diaper saying], “Gee, Mommy, you sure enjoy your Marlboro” [and the baby, again, in a companion ad], “Gee, Dad, you always get the best of everything… even Marlboro!”

Today, many states are entering the business of legalized, or medical, marijuana. Though pot will be available in many forms—brownies, cookies, oils, elixirs, etc.—its primary form will, nonetheless, still be weed, whose appearance resembles the spice, oregano. (Medical marijuana went on sale in Maryland on Dec. 1, as two of the state’s 10 licensees received their first shipments.)

This, in itself, has the potential of creating an entire new class of smokers. And once again, government, under pressure from recreational users as well as medicinal believers, is the enabler and beneficial partner. Tax-averse governments are constantly searching for new revenue sources by another name. But there isn’t an ashtray in sight. Smokers are society’s pariahs.