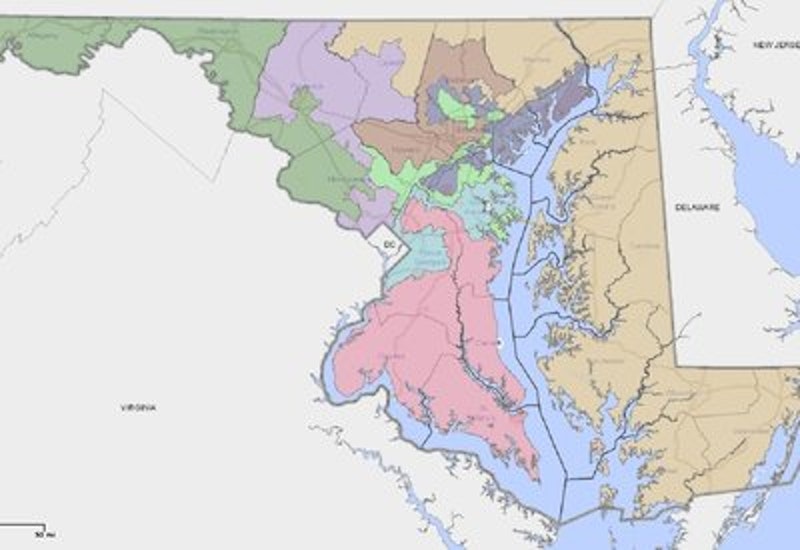

The gods bumbled when they designed Maryland. Many states come in neat, compact geometrical packages of squares and rectangles, but Maryland is a weirdly misshapen jigsaw of odd angles and jagged edges with a large flush of water separating its eastern shore and western mainland. Most of its population is clustered in five jurisdictions along I-95. The rest is geography. And because people choose where to live doesn’t mean they’re misplaced. To subdivide the state fairly and evenly is nearly impossible because of its Picassoesque shape; to have the courts try it is an invasive ac.

The redrawing of congressional and legislative district lines is a tetchy but vengeful business. A few squiggles on the map here, or the shift of a couple of precincts there, can make or break a political career. At its most cynical, redistricting often pits incumbent against incumbent with the surety that one must go.

When the General Assembly attempted to redraw congressional and legislative boundaries in the mid-1960s under the Supreme Court’s “one-man, one-vote” dictate, a fistfight almost broke out on the floor of the Senate. Sen. Frederick C. Malkus (D), the crusty Eastern Shoreman, accused Marvin Mandel (D), then House speaker and later governor, of “trying to protect the Jews in Baltimore.” Mandel, told of the inflammatory remark, promptly stepped off the House rostrum and marched over the Senate chamber. Mandel, who boxed flyweight in college, threatened to pummel Malkus, who outclassed Mandel measurably in height and weight. No punches were thrown. (The “one-man, one-vote” ruling abolished the old “unit rule’ in Maryland wherein each county had its own senator. Malkus’ Eastern Shore lost six of its nine senators.)

In the early 1960s, Maryland was awarded an eighth member of Congress because of growth in the state’s population. The ministers of influence in Annapolis were flummoxed over how to deal with the adjustment. So instead of carving out a new district, they created the extraordinary position of “congressman at-large.” The new position was won in the 1962 election by Carlton R. Sickles (D), of Prince George’s County, who, in effect, represented the entire state instead of a single district but without the portfolio of a U.S. senator. The office was later absorbed into the congressional map as the Eighth Congressional District, and, after many mutations, Western Maryland became the Sixth District, which is currently in dispute in the courts.

More recently, following the 2000 census, Gov. Parris Glendening (D) used the reapportionment maps to punish errant legislators and political enemies. Under the law, if the redrawn maps stray too far off kilter, the Maryland Court of Appeals will step in and edit them to its satisfaction. And that’s exactly what happened when Glendening attempted to reapportion several lawmakers from the east end of Baltimore County, and a few others, out of office. The court sniped back and Glendening’s adversaries won reelection under the court’s revised plan. (Unlike congressional redistricting, its local twin, legislative reapportionment, has certain criteria that must be met.)

So, drawing legislative boundaries to accommodate nearly six million people of all colors, socio-economic classes, geographic distribution and competing political parties is no easy assignment, even in the age of algorithms. Redistricting is like re-shaping with a balloon—squeeze it one place and it bulges in another.

That’s why the Supreme Court has often sidestepped the issue despite frequent appeals, though in two rulings it upended the process dramatically. In the “one-man, one-vote” ruling, the court decreed congressional districts must achieve population balance, really the only guideline that must be met. And in another, it agreed to step in when there was an egregious attempt to disenfranchise black voters.

Whoever is elected governor of Maryland next year—incumbent Republican Larry Hogan or one of eight (and counting) Democrats—can either thank or blame the U.S. Supreme Court following the 2020 census for intruding in the partisan process of drawing legislative district lines all over again. Or, the court might decide to take another pass. There’s no easy prescription. Many Congressional districts resemble runaway inkblots, and to try and depoliticize the political process is the worst thinkable solution.

The issue before the court this time is whether gerrymandering district maps to favor one political party violates the Constitution. The court chose a case from Wisconsin where a lower court ruled that the state’s Republican leadership advanced a redistricting plan that was so blatantly partisan that it violated the First Amendment and equal rights protections.

On a parallel track, the Maryland case moving through the courts argues that the redistricting map that followed the 2010 census was based on party registration and voting history. The map was designed specifically to defeat Roscoe Bartlett in Maryland’s Sixth District to assure that seven of the state’s eight districts would remain in Democratic control. Bartlett was defeated by Rep. John Delaney (D). Maryland’s Democratic leaders at the time, former Gov. Martin O’Malley, Senate President Thomas V. Mike Miller and House Speaker Michael Busch, were recently deposed after being denied executive privilege.

During the recent General Assembly session, Hogan had proposed legislation that would have created a non-partisan commission to draw legislative district maps. But Democrats have steadfastly maintained that they would go along with the idea only if every other state adopts the same approach, which, practically, is the only way it would work fairly. Democrats countered with a plan of their own—a regional five-state agreement to appoint non-partisan commissions. There were no other neighborly takers.

Republicans have the most to lose if the Supreme Court decides to end gerrymandering, which has dictated the rules of political engagement for nearly 200 years. Today, Republicans control 33 governorships and 32 legislatures and, through those twin power centers, are responsible for GOP control (and gridlock) of Congress, whose members rely on state lawmakers to draw friendly districts.

The word gerrymander was first used in 1812. Gov. Eldridge Gerry, of Massachusetts, signed a bill to empower his Democratic-Republican Party. When mapped out, one district in Boston was said to resemble the shape of a mythological salamander (probably the derivation of a Baltimore federal judge’s description of Maryland’s Third District, called the most gerrymandered in the country, as a “broken-winged pterodactyl.”)

Today’s methods of grabbing and maintaining power are just as blatant but more sophisticated, encouraged by how the two major political parties have evolved, mainly along racial lines. The two words often associated with redistricting are “cracking” and “packing”—in one case breaking up and scattering concentrations of voters, and in the other, lumping together similar voters. The most obvious application is the bleaching of districts to create predominately white and black districts. This has been carried out, in many cases, with the winking connivance of black leaders to assure safe black seats (at the same time they guarantee unchallenged white seats.)

Reforms often blow up because of unintended consequences. Consider campaign finance reform, one of the noblest of good intentions following the Watergate scandal. It unintentionally gave birth to political action committees (PACs.) By the time the Supreme Court reinterpreted the law under the misleading name of Citizens United, smokestacks became people and the law, as it now stands, has totally corrupted the political system with dark money.

Term limits is another good intention gone astray and away. Term limits was a key plank in Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America” that was supposed to remake the political system. But when those candidates who signed on to the contract were elected and got to Washington, they liked their jobs so much that they ignored the contract and their pledge and they stayed.

So be wary of any hope for reform of the redistricting process because it will only make a bad system even worse in the long run because there is no easy formulaic solution. And be especially wary of this Supreme Court which is more political than most and is sensitive to the elected officials who nominate and approve federal judicial appointments.