In 1975, John Demjanjuk was just another American immigrant who'd worked hard at the local Ford plant for years and had been an upstanding member of the Ukrainian-American community in Seven Hills, a Cleveland suburb. He had a loving wife, three children, and a settled life, but then his name appeared on a list that suggested he wasn’t the man his fellow Ohioans thought he was. One thing led to another, and Demjanjuk was eventually shipped abroad and put on trial for gruesome crimes against humanity. His story is the subject of the newly-released five-part Netflix series, The Devil Next Door.

The list contained the names of Ukrainians who'd collaborated with the Nazis. Ivan Demjanjuk (he changed his name to John in the U.S.) was serving in the Soviet army during World War II in 1942 when Nazi soldiers captured him and was allegedly sent to work in Treblinka, a German death camp in Poland. That's where he allegedly earned the moniker "Ivan the Terrible" after supposedly committing countless acts of physical mutilation and abuse against imprisoned Jews.

The tone’s set from the first scene, archival footage of Demjanjuk, a grandfather, attending church services with his family. He's the neighborhood guy who might shovel your driveway if you were sick. The viewer's left to reconcile two conflicting images, as if snow appeared to be falling on a summer day. You think you're looking at a content immigrant, but Ivan the Terrible was, as a narrator puts it, "One of the cruelest people who ever existed on the planet earth" when he operated the gas chambers at Treblinka, where he was known to push children into gas chambers and slice off the breasts of Jewish women with his sword.

The U.S. revoked Demjanjuk's citizenship in 1985, and deported him to Israel to be tried for war crimes. Throughout his ordeal, he steadfastly claimed it was a case of mistaken identity. The defendant's devoted children appear on camera regularly to reinforce this assertion. Directors Yossi Bloch and Daniel Sivan pile evidence on top of evidence that this solid family man had a previous Satanic incarnation that he'd left behind in Europe, and then they introduce a nugget of doubt (such as the fact that much of the incriminating evidence came from Russia, which may have had ulterior motives) that pushes you back to square one. This back-and-forth approach is typified in an extended piece of archival footage of the trial in Israel when a Treblinka survivor looks Demjanjuk in the eyes and calls him "the Devil," but then the defense produces the same witness's written, first-hand account of his fellow prisoners having revolted and killed Ivan the Terrible.

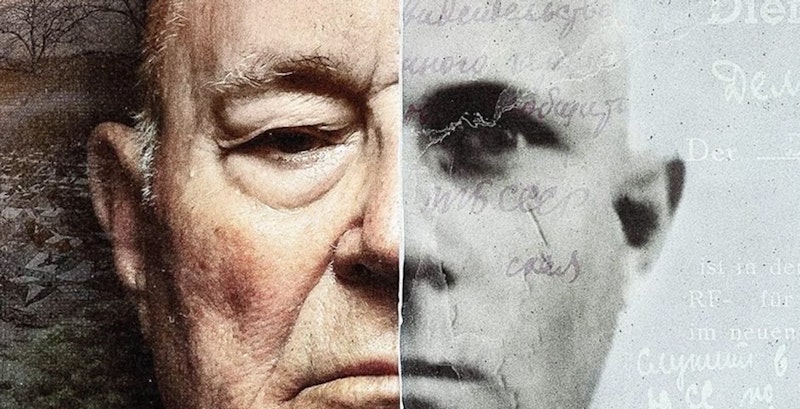

The photo of a man who's alleged to be a young Ivan the Terrible appears repeatedly throughout the film, and it certainly looks a lot like a younger John Demjanjuk. The widow's peak, the hair color, and the shape of the skull and jaw all look familiar. One expert witness at the trial says it has to be a photo of Demjanjuk, and you're ready to decide he's guilty, but then the defense's expert refutes her assertion so you back up once again.

Flamboyant Israeli defense attorney Yoram Sheftel, who appears at length in both archival footage and footage shot by the filmmakers, plays a central role in this film, which was a wise casting choice. Sheftel's steadfast denial of Demjanjuk's guilt provides a counterpoint to the exhaustive, often technical, slew of incriminating evidence the viewer's asked to process. This was a trial where testimony over the authenticity of the ink and paper on countless documents could drag on for hours.

Sheftel's contrarian conviction (he uses a Yiddish expression for "troublemaker" to describe himself) that Demjanjuk was wrongly accused was in direct and inflammatory opposition to the zeitgeist in Israel at the time. Emotions were at a fever pitch in a nation not entirely convinced that anyone who'd eagerly defend this brute wasn't guilty of a crime himself. It was the biggest Nazi-related trial since Adolf Eichmann was convicted in 1962, and it was looking likely to be the last of those trials.

Perhaps many Israelis saw that Sheftel wasn't merely acting out of a sense of professional duty in representing a pariah, but was actually enjoying himself. That made him into a national pariah, a risk that he was comfortable with, at least until an enraged fellow citizen threw acid in his face. The filmmakers say a lot with a shot of Sheftel slipping purple velvet shoes over his multi-colored polka dot socks.

Giving away the major details about what happened to Demjanjuk in Israel, and elsewhere, would rob the viewer unfamiliar with his story of some satisfying twists-and-turns storytelling. If you remember it (it was all over the news), you may wish the filmmakers had done, as some of their contemporary documentary directors have, their own independent investigation that might’ve provided some bombshells for extra punch.

Although the lack of new revelations may disappoint, the series presents an engaging cast of characters and a riveting story line that benefits from extensive archival footage of the televised trial. The Devil Next Door explores a number of important themes with skill, including Hannah Arendt's thoughts on "the banality of evil." Another, which may get buried under the weight of the underlying drama, is how loyal families can be to one of their own who's been accused of even the most despicable crimes. Demjanjuk was blessed in that regard. His wife, children, and especially son-in-law fought like badgers for him. In the end, that’s all he was left with.