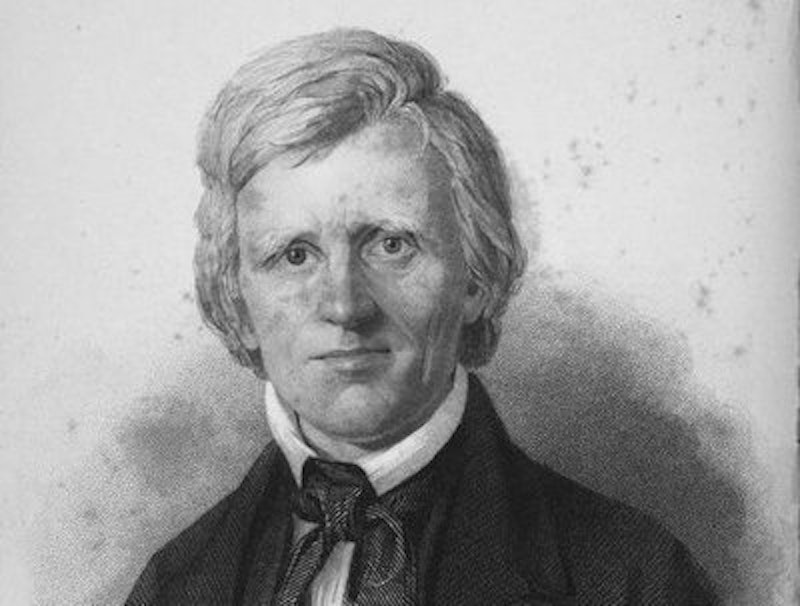

I know you've been wondering, so I'll tell you: the most radical American of the 19th century was an abolitionist newspaper editor from New Hampshire: Nathaniel Peabody Rogers. It's unlikely that you ever heard of him, though Thoreau wrote an admiring essay about him. But I think we still need his politics in the worst way.

Rogers started in the 1830s from a simple insight, but one that almost nobody applies consistently: people cannot own people. Like many of the most radical abolitionists—William Lloyd Garrison, for example, or Lucretia Mott—he regarded slavery not merely as an evil institution, but as the symbol of evil. Or, he regarded much human evil as a transformation of slavery: treating people like inanimate objects, annexing their lives or energies to projects not their own.

No one in America—and almost no one in the world, for that matter—referred to himself as an anarchist in 1840. But Rogers completely opposed the existence of government, which he held to rest in every case on force and coercion rather than consent. He held that the political state was a form of slavery, its true purpose the self-aggrandizement of its leaders. He regarded the characteristic function of government as warmaking.

Like Garrison, he was an absolute pacifist or “non-resistant” by the end of the 1830s. And like Garrison he saw that pacifism entails anti-statism, because the state rests on violence. I'm going to speculate that even Martin Luther King realized that commitment to non-violence is completely incompatible with accepting the existence of the political state. But he had other goals that required a compromise with power.

"Political action is of one spirit and intent with military," wrote Rogers in 1843. "The weapons of both are violence, and the instrumentalities of both, bloodshed and murder. What is government, after which all political action is aiming, but an armed battery? What is its voice, but the report of cannon - its sanctions, but the bayonet and the halter?"

Rogers started, as well, as an ecstatic political Christian, and like many radical Protestants, he read the Sermon on the Mount as demanding non-violence and universal equality of all people. But by the mid-1840s he’d grown extremely skeptical of religious institutions and referred to himself as an “infidel.” And perhaps he was moving off the pacifism as well by the time of his death in 1846. He kept hinting that slave masters ought to be hanged.

By that time too, or before, Rogers was a feminist, an environmentalist, and an anti-capitalist. He was almost alone in America in asserting that animals—even rats, for example—have “real rights.” It's often said that even white abolitionists retained many racist attitudes, but Rogers flatly attacked “color-phobia” and even laced into the whole idea of whiteness. "They feel free to enslave a man if he is not white as a diaper."

Thoreau admired Rogers' radical politics, which Thoreau emulated, but what he praised in his essay above all was Rogers' writing, which is at once plain-spoken and incandescent with outrage. "To speak of his composition. It is a genuine Yankee style, without fiction—real guessing and calculating to some purpose: free, brave, and original writing." As Rogers' friend John Pierpont said, the last thing you wonder after you read one of his newspaper articles is “Now, what did all that mean?”

And Thoreau also admired and emulated Rogers's nature writing: there are several passages in Thoreau that closely echo earlier writings of Rogers. For example, both of them often compared human beings under governments to horses and cattle being “broken.”

Rogers: “Good farmers are learning that there is a better way to treat their cattle than by blows. They are leaving off the practice of breaking steers and colts, for the reason that it is cruel: undeserved by the horse and unworthy of the employer, and because a whole horse or ox is better than a broken one. Political action is unfit even for brute animals. Is it fitter for man? A politician is but a man driver, a human teamster. His business is to control men by the whip and the goad. His occupation would be unlawful and inexpedient toward even the cattle.”

Rogers never composed a Walden, or any sort of book; all his writing was for newspapers, often quite short, produced on tight deadlines. And though his friends published a collection of his newspaper writing in two tiny editions after his death, he's never been reprinted since then.

One thing to realize about the politics of Rogers, or Thoreau, Lucretia Mott or Margaret Fuller: they were not on the left, and they were not on the right. There was no left or right in American politics in 1840. These people were radical individualists and radical skeptics of state power, which makes them sound like libertarians. But they demanded a host of radical changes—starting with the end of slavery—that leftists could’ve approved, if there'd been any.

The political left, which didn’t emerge in America until the end of the 19th century, got swept over and over into totalitarian solutions, extreme applications of power to try to create a transformation of the human species. Still, right now, there’s little to world leftism but statism, no solution to anything but a government solution. This, as Rogers would say if he were here, baldly contradicts the professed values of the leftists themselves both theoretically and practically. One wonders in the end whether the basic commitment is to the underlying moral principles (equality, for example) or simply to being dominated.

Since the turn of the 20th century we've been mesmerized by the left-right spectrum, transformed by it into twin rival camps of evil idiots. Well, there’s a beautiful history of American radical politics that has nothing to do with it at all. That's the sort of politics I want.

As befits a newspaper editor, and an American, and human being, Rogers was above all an advocate of the absolute right of free speech. "If it be not safe to entrust self-government of speech to mankind," he wrote, "there had better not be any mankind. Slavery is worse than non-existence. A society involving it is worse than none. The earth had better go unpeopled than inhabited by vassals."

—Crispin Sartwell's collection of Rogers's writings, Herald of Freedom, was published earlier this year. It's available on Amazon.