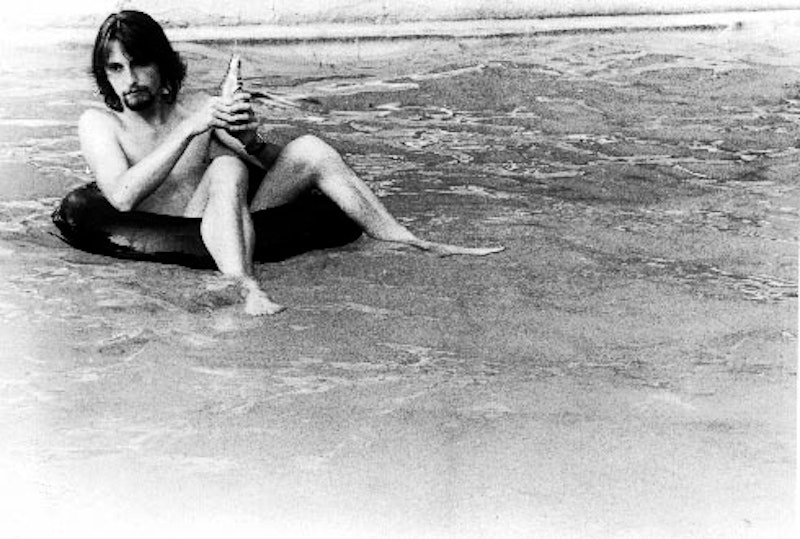

Joachim Blunck—known simply as JB to friends and colleagues—and I met in the mid-1970s while we were students at Johns Hopkins University. JB was the founding art director at Baltimore’s free weekly City Paper and was spirited away by the Village Voice, then owned by Rupert Murdoch, four years later. He then became a key cog in Murdoch’s News Corporation operations, most notably in Fox’s early television shows. Ever restless, he moved from Manhattan to Los Angeles in 1995, where he contentedly remains in the Westchester neighborhood, working on small-budget films, keeping tabs on the media industry’s current tumult, and is ready to pounce when opportunity strikes. The following interview was conducted by email last week.

Splice Today: You've been a media/entertainment professional since graduating from JHU in 1976. How can you sum up what's changed from the 70s to today in your business? What's better, what's worse?

Joachim Blunck: More, better, faster. When we were in school, I still had a black and white TV with only broadcast channels, a rotary dial home phone, read the newspaper every day, and did my schoolwork with a yellow pad and typewriter. To see a movie we went to a movie theater. Thirty-five or so years later, my daughter Kaley, who's a college junior at UCSC, has a large flat screen television with satellite reception, an AppleTV, a DVD player, a web-enabled iPhone, and gets news, entertainment and does her schoolwork on a web-connected MacBook—and she uses them all simultaneously. She goes to the movies, too, probably texting until the lights dim. There's more of everything, available to everyone, all the time.

Endless choices, and regrettably, endless junk. The misconception, though, is that everything is junk, which isn't true. The amount of interesting, high-quality material has grown as well. I've always maintained that everything adheres to what I call the one percent rule—that one percent of anything in any discipline is innovative and of real quality. Plumbers, mechanics, literature, art, television, movies—they all have their "bests" which we tend to seek out and emulate. It's in the emulation that things start to fall apart. So, a really great TV idea begets dozens of imitators, whether it's a procedural crime drama, or a reality competition. So it seems like there's nothing but junk, but if you look closely there are lots of people doing very good work.

On the downside, the entrenched media has screwed the pooch with regards to societal imperatives like a strong fourth estate. They abdicated classified advertising to craigslist, not understanding that the community bonding of classifieds is a major driver of circulation, and, with rare exception (one percent rule) were slow to embrace the web. This generation doesn't read newspapers, or even newspaper websites, for information. Television really hasn't stepped up to fill the void in an intelligent way. Reasonable political discourse is splintered into overly specialized forums that ignore each other.

I did a lecture recently at Hopkins to a class of media studies students. Just one read the newspaper, and he only did it when he visited his parents. They didn't watch any news channels regularly. But, they could hold forth on Housewives of New Jersey and The Real World in great detail. Johns Hopkins media studies students—presumably part of the one percent. Ugh.

ST: What are you currently working on?

JB: Pitching show ideas, writing spec scripts, doing meetings. We do lots of meetings out here. Like many producers, I'm trying to position myself for the world as it emerges from the recession. I've also been working with some longtime partners on low-budget documentaries. Last year our film The Seventh Python made the festival rounds. Now we're working on biopic about early 60s pop singer Chris Montez. I have an interesting iron in the fire that may bear fruit in the next month, but I don't want to jinx it. I'll keep you posted.

ST: During your lengthy career did you have one or two specific mentors/rabbis that helped you along?

JB: There was one in particular. At the Voice and later Murdoch Magazines I was close to a fellow named John Evans. When I arrived at the Voice, he was the Associate Publisher in charge of classifieds. He was an eccentric, brilliant and unforgettable Welshman who came to the US on a 40' sailboat from Gibraltar a few years before. We hit it off and he quickly introduced me to the higher ups at News Corp and guided my career up until Rupert Murdoch bought what would become Fox.

At that point, knowing my interest in movies and television, he helped facilitate my transfer. We worked closely during Murdoch's magazine expansion in the early 80s, and our mutual fondness for sailing brought us very close together. I embraced his non-lateral way of thinking and his very effective management style. He would go on to be a major player for Murdoch on the print and information technology side of things. He died suddenly in 2004. I ran across some video lately of a 1987 trip we took in the Caribbean on Zorra, an 80' sailboat that belonged to a boatbuilding friend of ours. It was very emotional seeing that again, and reminded me of how important he was to me.

ST: You left Baltimore's City Paper for the Village Voice in 1981. What was it like going from a ramshackle start-up to what was then an engine of weekly newspapers in the United States?

JB: Talk about letdown. The rap on the Voice at that time was that while it was certainly top of the alternative press heap, it had become a bloated, self-indulgent, self-important, aging liberal rant rag. It was all that, but it was still the Voice.

Within a month of getting there, the publisher who hired me as Production Director was canned, replaced by Marty Singerman, a longtime Murdoch confidant. He wouldn't even entertain a meeting with me. My first instinct—this coupled with the letdown of the reality of the Voice—was to leave. I was offered the Art Director slot at the Soho Weekly News. With one foot out the door, John Evans pulled me back, sat me down with Marty (who would become in many ways as important to me as John), and solidified my career there. It was Marty who a few months later introduced me to Murdoch.

At the Voice I was more an observer to the editorial process, and a cynical critic of the myopic self-importance of the writers. They made people like our (City Paper) colleague J.D. Considine look like lost puppies. These writers took themselves way too seriously, and copy editing was kept to punctuation and basic grammar. I did a bit of art direction there, and there was always a need to trim stories to fit—maybe have room for a headline (!) and a picture. Once I was laying out a Joe Conason column that was too long, and asked him to do a little cutting. The writers' reaction was always to look for jump space, but as head of production I minimized that for both aesthetic and practical reasons. Conason finally relented, trimming it to fit on the page with a headline. No picture, but off the column went to press.

It wasn't my place to mix in, but later I couldn't resist pushing his buttons. I told him that after reading his piece I thought it could have shrunk quite a bit more, without losing the thrusts of his arguments. He took the bait and asked me to show him. I crossed out all the adjectives, and its length dropped by more than a third. It was on point, crisp, and an arguably better read. He wasn't amused. I wouldn't be doing any more editing until I got to television, where tight, clever, economical writing rules.

ST: You worked for Rupert Murdoch for a number of years, with A Current Affair, Good Day New York and the FX Channel. How much interaction did you have with Murdoch and how much autonomy did he give you and your colleagues? What led to you severing ties with News Corp and do you regret it now?

JB: In my early days at News Corp it was still a relatively small company on the executive side. One of my many hats was to work at the corporate offices on a variety of things for Murdoch. I had my share of meetings and interaction, and got a good fly-on-the-wall view. It was during that time that I gained enough trust to be thrown into Fox with a couple Aussie journalists, and basically set loose to do whatever had to be done.

A Current Affair was the answer to Murdoch's request for an evening news show. Murdoch had considerable interest in our progress—he regularly spoke to us, and was present at a couple early, formative meetings—but the interpretation and execution was left to us. Peter Brennan was the editorial heart and soul of the show; I worked the visual style and got it to air. Sound familiar? We were housed at the Fox NY station, the former Metromedia WNEW. There was no help—we were Murdoch interlopers. I remember putting together equipment and people, spending what would become millions of dollars without regard for the internal accounting systems. The show went from concept to air in less than eight weeks. If anyone ever asked "by whose authority," I just said "Rupert." That was fun.

Later at Good Day I would be running the whole shebang. We took a dead-as-a-doornail idea and turned it into a lasting, successful franchise. It took three months to pull the show from eighth to second place in New York. Murdoch called occasionally (usually at three a.m. from a jet somewhere) to ask how things were going, but he never interfered. If he had a concern, he'd let me explain my position and nearly always said, "Well good then. Carry on." I think if my ratings were bad it would have been an entirely different matter.

Murdoch's phone calls could come at very opportune times as well. In 1989 I produced the first Fox New Year's Eve Broadcast live from Times Square. It was an amalgam of street bits, taped comedy, live music, and was hosted by Penn & Teller from the roof of the Marriott overlooking the crowd. The production was switched from a cramped trailer at the base of the building that holds the famous ball. Remember, this is live television, no delay, something rarely done at the network. They sent along a nervous senior executive to "chaperone" me. Anyway, we had Southside Johnny performing at a Manhattan club party, the feed incorporated into the show. As he took the stage, the picture going out live, he shouts into the microphone, "We're gonna party like a motherfucker!" and starts playing.

The exec, sitting next to me in the broadcast trailer, starts dialing furiously on his cell phone (the old Moto brick). Of course, there was no signal, and he starts buzzing in my ear to do something. I ignored him and the show went on. He fumed. Just after midnight, Penn & Teller do the classic rope/knot magic trick, but they do it with a live snake. They tie the snake in a knot, and then seemingly cut it in half with a pair of scissors, awkwardly hacking at it (it was a very juicy sausage). All the while the Fox exec is imploring me to cut away. No chance. Finally, after another remote routine, Penn & Teller strip to their underwear in the 20-degree weather. It's great television. The exec is apoplectic. The show ends, he starts yelling. Everyone in the trailer is staring at him as he goes off on me. The private landline phone in the trailer rings. It's for me. I interrupt the exec and answer. "Hi Rupert … oh thanks, glad you enjoyed it … yes, that was funny … okay … thanks, I really appreciate the call. Bye." Silence. The Fox exec took off into the night. I was back the next year to do it all again, with Penn & Teller.

The FX startup went the same way. Tons of autonomy, lots of money flowing, and occasional support in the form of a call or a visit. You always knew Murdoch was watching, because his comments and observations were uncannily on point. I don't know how he had the time.

In my time at News Corp I was never afraid for my job, and always felt supported. I left after moving to Los Angeles. New York was an oasis in the television system, and our distance from Hollywood and proximity to Murdoch made things easy. As long as we succeeded and delivered, we were left alone. In LA, everyone gets into your business and looks for ways to either piss on or co-opt your work. It wasn't fun anymore, and I had my fill.

In hindsight, I certainly could have made things work. My career since has not had the rush of those years. Some regrets, and maybe I'd do it differently now, but I'm happy with life. Kids do that for you [in addition to Kaley, JB has a son, Zach, 16]—my focus changed.

ST: When A Current Affair started its buzz-meter was off the charts in New York, with personalities like Steve Dunleavy and others landing in the gossip columns and just a lot of excitement around the show. I imagine it was a rush to be a major domo on the show, if exhausting. What was the atmosphere like? Maybe like an extended coke/meth high or something different? And how do you look back on those Fox shows today? I see that you did the "Color Correction" for the film Outfoxed.

JB: Not drugs, but an awful lot of liquor. We had a phone extension installed in the bar across from the office. We were reinventing storytelling for television. No one had ever seen anything like it, and we were too naive to say no to anything that was suggested. We were renegades with a healthy sense of humor. It was very much the same outlaw mentality that we had at City Paper.

People often think back to ACA as tawdry and salacious, when in fact it was just good tabloid reporting with a twinkle in our eyes. If you got the joke, fine, if you didn't, at least you were entertained. In our first month we got a positive review in The New York Times! The reviewer got it. For the most part, so did the audience, and the rising ratings just fueled our daring.

Aside from the preppie murder, Jim and Tammy Faye, and all the other big stories that we led with simply because no one else did (that changed, didn't it?), the one I remember with a laugh was the Peter Holm story. Holm was a dumb hunk of a Swede who was being divorced by Joan Collins. He sued for palimony in LA Court. We put together, in a day, a show (live to air at the time) that was a mock telethon to raise money for Holm. Our studio had been used for years for the Jerry Lewis Telethon when it came from New York, so in the rafters were phones, tables, chairs, risers, decorations, all the stuff you needed to do a telethon. We set up the studio with mock phone banks populated with celebrity lookalikes (and Cindy Adams), did a backdrop with a tote board that looked like a big thermometer (The Peter Meter), recorded tape packages with New Yorkers and what they would donate (a slum apartment, food from the trash, etc), ran a text zipper on the screen with amounts people were giving (all fake—Joan Carson $1000 … Joanna Carson $10,000), and had the telethon portions of the broadcast hosted by one of our reporters in a tux.

Maury Povich, of course, would not lower himself to our descending levels, and hosted the "show" from his usual set. The show did include an actual package about the trial, but the capper was a satellite interview with Holm as he left court that day. He, of course, could hear our show in his earpiece between Q&A sessions with Maury. While a viewer would have seen the obvious satire, hearing the show interspersed with Maury’s conversation seemed to give a different impression. After the show was over I got a call in the control room from our producer in LA. Holm wanted to know how much money we'd raised.

ACA, Good Day, the FX shows and everything else all had the same sensibility. I had the time of my life. Of course, we begat a tectonic change in news. There are no more tabloid news magazines. Everything is just tabloid, and without the consideration and execution that we invented. News is now salacious and tawdry, and increasingly stupid.

Not much of a story with Outfoxed. I do color work on occasion to bridge between producing assignments. It was a four-day gig. The producers of Outfoxed made some good points, but on the whole they were as misinformed as everyone else.

ST: Do you follow the continuing acquisitions, plotting, subterfuge, etc. of Murdoch today, and do you think, as is commonly thought in some quarters, that he's an evil media force? Or, rather, an old-fashioned entrepreneur?

JB: Success breeds detractors. Murdoch succeeds. He is fearless and incredibly smart. It was always an eye-opener seeing him run a room. He listens, considers, decides, and more often that not, provides the initial idea that fuels the machine. In media, he's the last of the old-time journos.

Politics aside (and I think Fox News is awful), his moves in publishing were always copied, whether it was changing the game with the unions or using technology to further coverage and production. He's leading the charge to save what's left of real reportage. The Wall Street Journal and Harper Collins will be among the first on the iPad. Murdoch understands more than anyone that newspapers represent power, and that he and the rest of the industry failed to understand the impact of the Web. Unfortunately, his people screwed up MySpace. My impression is that the touchpad moves are being encouraged directly by him. Will it all work? Dunno.

ST: You left Manhattan in the 90s for Los Angeles. I remember at one point you had a serious bicycle accident: did that affect your desire for a change of scenery? And, though I doubt it, have you become a bicycle rights activist?

JB: The bike accident did help drive me to get out of Good Day and expand my horizons. Despite the success, I was getting bored. FX was next. In my career I've tended to move from startup to startup, trying not to repeat myself, adding to my experience. Not good for a settled career path, but a great ride.

And no, not a bike activist. I still ride—the beach here is great for that—and I use a motorcycle to get around LA most of the time. Death wish? Nah, I just like the implicit freedom of two-wheeled transportation. I've always wandered. I'm not sure what I've been looking for.

ST: One time you told me—this was in the late 90s—while we were talking in Malibu, that Hollywood was a dead end for people over 40. Do you still feel that way?

JB: What was Hunter Thompson's music industry quote that was bastardized to TV? It's true.

If you haven't made an impact by 40 or so, it's very hard to keep up the game as an independent. TV execs like their ideas coming from either young people, or people that they've worked with successfully time and again. I never established myself in film, and my sprint-from-here-to-there career has not given me a strong base. I tend to innovate my way forward—I'm still here, and I'm still trying to do new things.

I've sensed a bit of give in the system in some ways. There is a distinct need for experienced people to guide the up-and-comers. It happens, but it requires that the old timers check their ambition, and the young turks open their ears. I've worked with some very talented young producers, and the experience has been rewarding.

ST: When I describe you to friends, I've always said that you were consistently a few years ahead of the rest of the media pack. For example, when you helped me out by designing New York Press in '88, you made the decision that the weekly should be produced on desk-top Macs, which no other weekly was doing at the time. Do you still feel you've got a pulse on what's going on in the industry or have you taken a step back to relax more, spend time with your kids, etc. You once told me, "Some people work to live, I live to work."

JB: I still live to work, but the kids have tempered my ambition for the better. Like I said, I tend to innovate my way forward. The trick has been finding environments that let me do my thing, and on the whole, I have. Several years ago I moved Bunim-Murray Productions (The Real World, etc.) away from industry-standard Avid production systems, to one being developed by Apple. I ran the largest beta test, and developed the workflow for what is now the de facto new standard: Apple's Final Cut Pro. Cool stuff.

I went on to work with the nascent capabilities of Flash Media Server, and developed several interfaces that are found in bits and pieces around the web. I've done my share of website work, MMOGs, commerce. The future still includes TV, but not necessarily TV sets as we know them now. There are technologies coming down the pipe that will cause yet another shift in our enjoyment of media. I'm still plugging away and trying to ride that wave.

ST: Do you think all aggregation websites are going to prosper or will some fall by the wayside? What websites do you check in on every day? And what's been your own online experience?

JB: More and more people are their own aggregators. Despite the enormous number of choices, I think people have a tendency to find comfort in a small array of sites that they learn about through friends. I look at everything I can and find the overall lack of real innovation depressing. The missed opportunities are everywhere.

I think if you can look beyond the pornographic crap, ChatRoulette is a marvelous idea: it plays to our worst fears and desires—what if it could be harnessed in a useful way? People of Walmart is a hoot. Personally, my daily tabs hold a mixer of old-school news, technology, video, cars and bikes, weird sites, and a couple of blogs.

ST: What do you think the media/entertainment industry will look like in five years?

JB: I think the industry in general has the whole web thing inside out. TV people hate web people; web people think TV people are dinosaurs. But that doesn't matter in the end.

Big corporations are run by people who are risk averse, so there is a distinct lack of risk-taking unless it's driven by emerging technology whose long lead-time to the market makes adoption inevitability. Satellite distribution drove cable and forced a change in viewer habits. DVD technology forced major changes in production economics. TV on the web is forcing a complete reconsideration of the presentation and advertising model that's existed for 50 years. The technologies are not driven by storytellers, they are driven by technocrats. The creative side plays catch-up and does its best to adapt the new technologies to our caveman legacy as storytellers. The business people just want it fast and cheap.

The only consistent truth is that people like video in all forms. Chat, texting, news, gossip, information, all eventually feed into it. The company that can cohesively bind all the pieces of the puzzle and make them relevant to daily life will win in the end. No one does that yet.

I have plenty of ideas, if anyone is willing to listen. Ha!