There was a woman at the nursing home where I used to work who spent the bulk of her time in bed. Her other activities included defecating and urinating in her diaper, eating, sleeping, and receiving a bath every other day. If human life is measured in what we do, then these activities struck me as a life not worth living. She had advanced dementia, and imagining her frail body in my mind, frozen in permanent horror from muscle contracture, was enough to make me secretly appeal to any authority, earthly or otherwise, for her death. I often wondered why she couldn’t be prescribed a drug that would end her suffering.

I’d think of her even off the clock, but seeing her and tending to her needs was far worse. When assigned on her wing I’d make sure to visit her first to have the unpleasantness out of the way. Rules required that residents who were bound to their beds and immobile must be turned every two hours to prevent bed sores. I’d first inspect her diaper for waste, then, if it was clean, I’d turn her to her right or left side (she was frozen in the fetal position, there were only two options). Upon completion I’d exit the room like fleeing a haunted house.

When she was conscious, she’d vocalize a repeated and rhythmic groan that struck my ears like a deep pain for which there was no remedy; a pain that emanated from her soul. She was suffering unspeakable horror, or so I believed. But only in retrospect did I realize that it was not her suffering that I wanted to end, but my own.

Proponents of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide argue that those who suffer from terminal illness, and have less than six months to live, should have the choice to opt for “medical aid in dying.” This practice allows a doctor to prescribe a substance that the patient would have to choose to ingest. The patient then dies in their sleep.

Proponents go to great lengths to explain that this process is not “physician-assisted suicide” or “euthanasia.” But when a physician provides a substance that they know will terminate life, they’re facilitating suicide. They might as well offer a loaded gun. It’s important not to obscure killing with comfortable euphemisms. The two words I most often heard from residents in the nursing home were “I’m sorry.” These words were most commonly spoken whenever a resident needed something (diaper change, food, water, the occasional trip to the toilet for those who retained some degree of mobility) that they couldn’t provide for themselves. The guilt and shame they’d express may come as a surprise, but I suspect most of us will understand that we are compelled to justify our existence.

In our society one of the metrics by which we judge the value of a human life is measured by what we can produce, and when illness or injury occur, we begin to consider ourselves burdens on others. This can lead us to dark psychological states, including the thought that it’d be better if we’d simply die, and as such cease causing trouble for others. But we’re all burdens on someone, all the time and throughout our entire lives, so the point is moot. Elders in need of care must be freed from their suicidal ideation, not have it catered to by those who are indifferent to their lives, or incentivized by their death, even for those who suffer terminal illness. Once the choice is offered for a person to have the option to end their own life with the help of a physician, it can create murky and potentially dangerous dynamics where the choice could become an obligation.

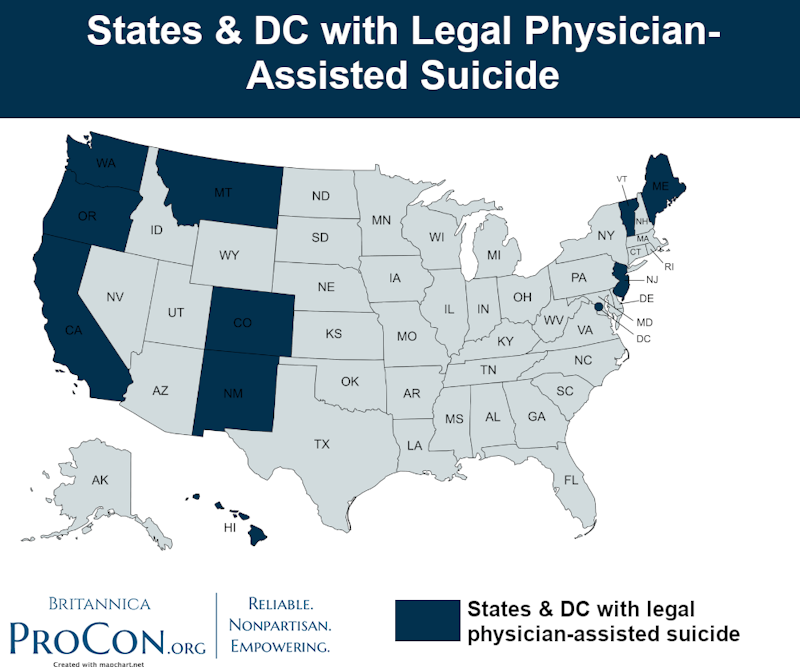

And this leads to one of my chief concerns—what of future generations? In George Orwell’s Animal Farm, there’s the character Boxer. He plays a chief role in building up the farm and especially the construction of the windmill. One of his constant refrains is, “I will work harder,” and he does. He works until his body is broken, and then he expects to be put to pasture to enjoy his final years with pride in all he has accomplished. But instead he’s sent to the glue factory and murdered. This comparison might seem hyperbolic. But consider that 11 states have already authorized euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide, and several more states have bills in various legislatures. Americans ought to consider this issue carefully and not allow the euphemisms to blind them to reality. There will be consequences for our descendants.

—This essay was inspired by the What’s Left? podcast episode “The Work of Choice.”