“Oh well,” the narrator says, and also “I hope so, too” and “Quite right” and “No, not really” and “It seems rather hard to say.” These wan rejoinders run through Doris Lessing’s “The Day Stalin Died” and provide the story with its final line: “‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I suppose we will.’” The narrator—literary protocol forbids calling her Lessing, but find a difference between the two ladies—dispenses her polite, half-interested remarks at the same kind of moment that everyone does: that is, when the foolishness of others starts to crowd in. “Mummy is coming, too,” her cousin says, and the narrator knows family drama lies ahead. “Oh well,” she says. Mummy, officious, says to the narrator, “I hope this man of yours is going to do Jessie justice.” She means the photographer the narrator recommended. The narrator has made very plain to us that this recommendation was offered under duress; Jessie’s mum had refused to listen when told that the narrator knew little about finding a photographer. “I hope so too,” the narrator says. Or there’s Comrade Jean, the pious stalwart of the Communist Party. “We will have to pledge ourselves to be worthy of him,” she says, meaning Joseph Stalin. The narrator: “I suppose we will.”

The story: a writer in London is stuck for the afternoon with relatives from out of town, and it’s the afternoon that the world learns Stalin just died. Lessing, or the narrator, has spent years as a Communist. But this day she’s saddled with cousin Jessie, a good-looking but rather fraught girl who’s getting no younger, and Jessie’s mother, who has a “big, heavy-jowled, sorrowful face.” The girl and her mother, broken-down members of the gentry, live in a boarding house and “carry on permanent guerrilla warfare with the lower orders.” And why not, the narrator says, since the women’s lives “are dreary in the extreme.” On the other hand, for a while now Communism has struck the narrator as being an even bigger loss than her relatives. Before her afternoon with Jessie and mum, the writer has to spend lunch enduring a lecture from Comrade Jean, the topic being the writer’s unfortunate tendency to heed reports of awful doings in the Soviet Union.

“The Day Stalin Died,” when viewed as an example of literary fiction’s show-not-tell tendency, adds up to an unstated, sideways portrait of a state of mind. The central belief of your life has remained central to you but has lost most of its supports. What is it like when you then experience a world-historic event that’s tied to this relic faith, an event that you really ought to find momentous and tragic? Well, as things turn out, it’s kind of underwhelming, says (no, shows) “The Day Stalin Died.” It isn’t the death of Stalin the woman must absorb. It’s how little the death matters to her. See how deadly “suppose” is in the story’s closer.

Lessing wrote the story hard upon the event, and her autobiography reports that party headquarters didn’t like what she had to say. Three years later she finally left the Communists, and six years after that she produced The Golden Notebook, a mammoth novel charting the passage into and out of breakdown of a Lessing stand-in who has fully taken Soviet Communism’s measure. “The Day Stalin Died” is about a Lessing that doesn’t feel much about the death of her faith’s leader. The Golden Notebook is about someone who comes unpinned because she can no longer believe in the dream that Stalin represented, this dream being the belief that mankind was building its millennium when actually thugs and fanatics were torturing a population. Lined up this way, the two works make it tempting to think that the narrator of “The Day Stalin Died” is simply numb, as when emotion is so great that feeling must be postponed.

But she doesn’t seem numb. Her tendency toward the acerbic is lively. With lifted eyebrow, she lays out for us the antics of Jessie, Jessie’s mother, and the winsome pair of young men condemned to try photographing Jessie. Comrade Jean is guyed as well. This dutiful creature recommends that the narrator spend more time with working-class people to cure herself of wrongthink (or, as the narrator dryly paraphrases, to “mix continually with the working class” so that her writing “would gradually become a real weapon in the class struggle”). Comrade Jean, you schmuck. The narrator already talks with the working class, for whatever good that’ll do the party line.

Going about her business on that crowded afternoon, the narrator chats with a taxi driver and a news vendor (“an old acquaintance”) and gets an earful about the first fellow’s daughter problems and the second man’s views regarding the healthy life and the late Stalin. Too many committee meetings, too much time looking over reports, says the news vendor. “That’s why I like this job,” he says, “there’s plenty of fresh air.” Or look at the cabbie who once laughed at poor cousin Jessie after their battle over her fare. “That’s a real old-fashioned type, that one,” Lessing recalls him saying. “They don’t make them like that these days.” This encounter demonstrates a particular point. It’s not so much that the working class has won, more that the old order is dilapidated. Still, here comes equality, and does Comrade Jean know it? No, she’s too high-minded to see what’s up.

Reflecting on “The Death of Stalin,” Margaret Drabble writes, “as this story illustrates, correctness does not fit easily with the messiness of human behaviour.” It’s the lesson ideologues must always learn: humanity is people and people go off in all directions. (The point keeps being forgotten, which is one reason it’s been repeated so many times.) Lessing had a galactically wide focus: the global scale of Marxism looks small next to her novels about cosmic history. But along with this focus she also had a downhome, hello-stranger approach to humanity’s local representatives. She was quite comfortable with taking us one by one while trying to chart what lay behind the species, behind reality, behind everything else.

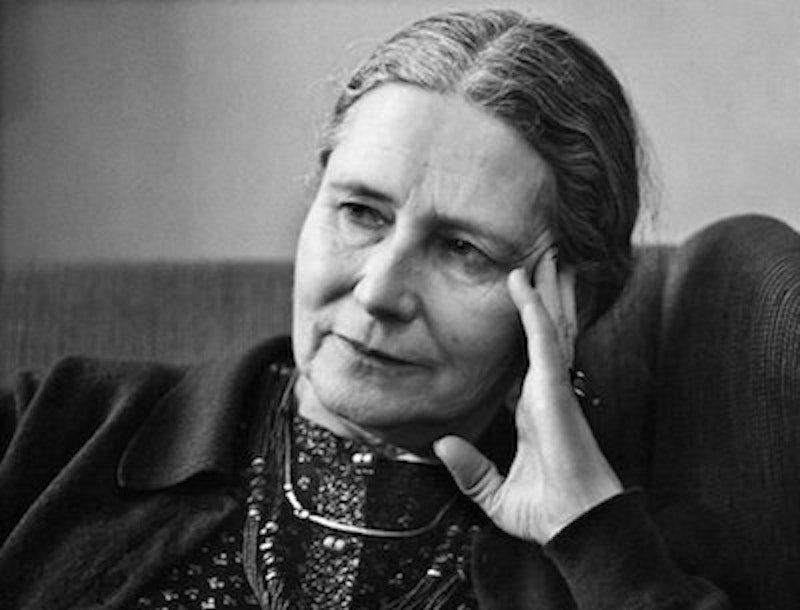

As a writer and a person, Lessing makes one think that somebody bought the rights to Margaret Thatcher and made her a novelist, a left-winger, sort of a mystic, and you know, likable. Check out a photo of Lessing and you’ll see she had the Gaze of Power. If she looked at a wall, the wall got out of the way, as did (at various points in her intellectual life) capitalism and false consciousness, the ego and its miniature stage set, and the human view of our universe as a place where we are and nobody else happens to be. While shoving about our assumptions in her brisk way, Lessing always stayed the same person, and to read her is to enjoy her company, if also to marvel at it. No matter how big the doings, she wants us, the people at hand, to get the lowdown, which she rattles off in her loping, sensible-heels prose. She speaks person-to-person, and her person possesses the intelligence and brio to try sorting through the giant questions we all have hanging about us. She’s also honest enough to admit when the going has gotten tough and her answers are tilting over.

Of course, she was a fool about Communism. She says as much in her autobiography, recalling the young days of cigarettes and party newspapers and hashing out home-made political analysis. The Lessing of the autobiography says that now she knows Stalin was worse than Hitler, “a thousand times worse.” She knows that she fell for dreadful lies, and that she felt clever while doing so. She wonders if she’d have said yes to mass murder if fate had made her a smart, eager activist in Russia or China instead of Britain’s imperial boondocks. Here I butt in to stress that the girl proclaimed herself a Communist when she wasn’t yet 24, and that up close, in the realm of people, she found that Communism was largely a matter of hanging out with stimulating friends while opposing Southern Rhodesia’s racist oppression of Africans. On the other hand, 1939 is a hell of a year to start believing in Stalin.

In theory, the young Lessing took leave of her husband and two children because the world needed her help in reaching its Marxist transformation. Really, I expect she just wanted the life she wanted. She married at 19, thereby breaking out of her existence as the self-educated daughter of a farming couple in the bush.Then she shattered her existence as a young housewife in town, leaving husband and family to be a bohemian and thinker, sitting on floors and taking lovers. She did this by becoming a Communist and seizing a mission in life, but that delusion would last only so long. Finally, she was a woman in London with a typewriter, a flat, and a published book, and she noticed cracks were spreading across her personal sky. Reality, otherwise known as Communism, couldn’t hold together. She’d have to break through again.

Before she did so, Lessing wrote “The Day Stalin Died.” I opened with a list of the story’s wan rejoinders. Let’s say that “Stalin” catches Lessing on a bad day. Relatives and world-historic disenchantment can put a crimp in one’s mouth. Still, we have her thoughts on cousin Jessie: “‘It doesn’t matter in the slightest anyway,’ said Jessie, who always speaks in short, breathless, battling sentences, as from an unassuageably painful inner integrity that she doesn’t expect anyone else to understand.” I find that sympathetic as well as penetrating, and managing to be either is a feat while you’re irritated, let alone absorbing an immense moral and intellectual fiasco.

“The Day Stalin Died” is a day when Lessing, or the narrator, senses how far Communism now lies behind her because the death of its alleged great man leaves her with so little to feel. It’s also the day when her cousin tries to sit for photographs and makes a hash of it. The cousin’s misadventure occasions the most noise, but we see the narrator reading about Stalin in the newspaper and feeling peeved because the photographer’s rather vocal assistant is looking over her shoulder (“Obviously outlived his usefulness at the end of the war, wouldn’t you think?” “It seems rather hard to say”). Somewhere behind all this, small as a square of newspaper print, lies Stalin’s death.

The fuss about Jessie’s photograph is a single episode in one of the crushing dramas lived by the British middle class. Jessie’s mum thinks that a picture will ger her girl a TV contract the next time one of their fellow boarders is visited by his brother, who’s a producer. Jessie, meanwhile is rotting alive and entering the second half of her 20s, and she wishes fiercely that her mother would leave her alone. “I would like you to catch her expression,” mum tells the photographer. “It’s just a little look of hers.” In response, “Jessie clenched her fists at her.”

Perhaps the look in question is the fierceness, the “breathless integrity of indifference,” that Lessing describes in this trapped being. If so, the photographer is subjected to the look in spades. We don’t know, because the shoot takes place offstage. But it ends quickly and unhappily; apparently the girl has blown up this latest of her mother’s intrusions. Good-byes are said. “Jessie turned to the two men and thrust out her hand at them. ‘I’m very sorry,’ she said with her fierce virgin sincerity. ‘I’m really terribly sorry.’” She goes back to the boarding house and a lifetime with mum. “We descended into the street,” the narrator says. “We shook each other’s hands. We kissed each other’s cheeks. We thanked each other. Aunt Emma and Cousin Jessie waved at a taxi. I got on a bus.”

The narrator goes on to her destiny; if this resembles Lessing’s, it includes big doings done on her terms. For tonight she receives a phone call from Comrade Jean and commiserates in her reluctant way: “‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I suppose we will.’” She’s wondering about the foolishness of us all, us humans. That attitude has a bit of crust, considering she joined the Communists after the Nazi-Soviet Pact. She’d hardly see two of her kids again, and the reason she gave for leaving them was a mirage already shown to be a mirage. But it had served its purpose, and she’d just have to come to terms with the rest. In the meantime, Stalin was dead.

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3