The guilt hounded me like a three-year-old wanting to know “Why is the sky brown?” How do you justify fossil fuels to a child who has yet to learn the meaning of “value?” But it was that impertinent guilt that forced me to sell off my dirty stocks, and this is the story of the tanker voyage I took to get there.

I was 10 when I began to learn the lies of “value” in all its capitalistic glory. Specifically, I asked my father, “What is the stock market?” Dad, a knowledgeable and patient man, explained the world of investment to me in the best terms anyone could muster. From our The-Bulls-&-The-Bears talk, I came to understand that by posing as part-owner of a major corporation, I could become filthy rich. I was momentarily intrigued by this revelation. Then I went forth to climb my favorite tree, a snaggled old cherry in our front yard. By bedtime, the stock market fantasy had been replaced with the memory of a snakeskin caught in the forks of the tree. That was that.

But then my father played a cruel trick on me. He bought me a share of stock as a Christmas present, the certificate wrapped up in a tube of Santa paper. (I wish I’d been wise enough to see the irony of that back in 1971). I now owned one share of Ashland Oil, Inc. The certificate showed a naked man with a blanket draped across his genitals. He was seated by a table of chemistry equipment and held beakers in his hands as though he were measuring the concoction that would make our very lives run. He looked noble, as he imitated the notion of a Greek scientist.

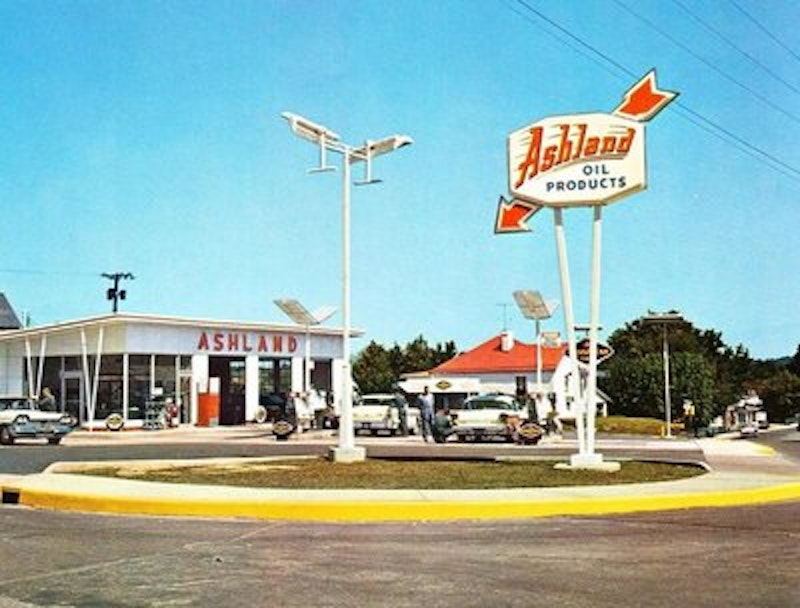

At the time, I was elated, for there was a full-service Ashland Gas Station in my neighborhood (Ashland, KY, the city namesake for the company, was just a few miles from my doorstep as well). Since I frequented the station to put air in my bike tires, I now felt like the proud owner of the air compressor—or at least the hose. I felt justified to get free Ashland Oil stickers from the mechanic, though I never told him I was one of his bosses. And, like a clockwork derrick, every three months I got a dividend check for 35 cents—for doing nothing at all. Back then, 35 cents was 35 pieces of Bazooka bubble gum. I rode my bicycle on Easy Street.

Dad had spent about $30 for the stock, and every few days, I would check its worth in the local paper. I smiled when it went up and frowned when it went down. Then I read the funnies. The innocence of childhood kept me from the oil stain of guilt.

In the mid-1970s, America entered the “Oil Crisis,” a major shortage that threatened our very way of life. In a slap of fate, it appeared that the Middle East was floating on crude. God, in all her twisted humor, had put our oil under their sand. Still, I suffered through it, as my dividend checks surged to 55 cents.

In the years that followed, I watched the price of my stock and earnings rise and fall. There were mergers and stock splits that would produce other, larger checks. I entered a stock reinvestment plan, my meager earnings going to future shares instead of bubble gum. As my diabolical father had intended, I learned what the stock market was about: from the “American Dream” to the smoke and mirrors of the thing. Guilt began to seep up from my moral earth.

It was in the late-80s that I first heard of global warming. Almost immediately I saw the logic in the science and accepted the theory as probable fact. And the guilt began to flow. I was part of the problem—even though I only owned about 1.38 shares. Every time I cashed my little check, I felt a pang of remorse for my contribution to the ruination of the planet.

By the turn of the century, I had two full shares in an oil company at a time when the industry was sinking trillions of dollars into “exploration,” drilling wells only to cap them off as future money spouts (think on the BP disaster in the Gulf of Mexico). It became clear that even when the reality of global warming caught up with us, the oil industry would still have to tap that oil to pay back over $1,000,000,000 to its stockholders. Otherwise a global economic depression the likes of which we’ve never seen would toss humanity under the smoke-belching bus. Even as CO2 emissions began pushing our planet to the brink, the oil companies argued their only option would be to eventually to use the reserves. That was the stockholders expected, demanded. And, to add value to that stock, the industry needed to keep on drilling.

The act that finally put this into perspective for me? A Russian submarine planted the national flag on the sea floor at the North Pole. Once the Arctic ice is a quaint memory, Russia will drill under what was Santa’s front porch.

Then, in the summer of 2008, something truly enlightening happened. We had another oil shortage (though somehow without the 70s images of cars sputtering on fumes as they waited in endless lines for gasoline deliveries). Prices at the pump surged to four and five dollars a gallon. I paid $4.11 a gallon at a convenience store during a trip to North Carolina, the most I’ve ever paid. Many people were stuck with their SUVs and trying to get to work to pay the bills.

The talking heads of cable TV argued over whom, if anyone, was profiting from this shortage. While the oil companies stated they were merely passing along costs, unrestrained economists demonstrated that simple multiplication, as opposed to addition, created, in the long run, higher profits for the industry (a typical smoke and mirrors trick). By then my dividends were a staggering $1.10 (55 cents a share). Hardly enough to impact families choosing between filling the tank and making their mortgage payments, I reasoned, but I still felt guilty.

Then my October dividend check came. It was for $22. If I’d kept the records and averaged out my dividends from 1972 to the summer of 2008, it would’ve come to less than $1. I suddenly had a check for 22 times that amount. To put it another way, at four dividend checks a year for 36 years, I’d received less than $144. Now I was staring, aghast, at a $22 check.

But this check represented a sliver of a sliver of the pie. There are, of course, individuals who hold thousands or tens of thousands of shares. Imagine the size of their checks. Ashland Oil is a Fortune 500 company with its fingers in over 100 different countries. It employs over 14,000 workers, and its revenue for 2012 was over $8 billion. And in some tiny way, I had helped build that empire.

Middle-class America was losing jobs and homes at the beginning of the depression (I find “recession” an insult in this case) of 2008, and Ashland stockholders were getting checks for tens of thousands of dollars or more.

Why? No explanation came with the check, so I searched the company website. It informed me that these were bonus checks for faithful stockholders. I called bullshit. The timing couldn’t have been more damning. When I cashed my $22 “bonus check” at my little neighborhood bank, I felt the guilt dagger plunge into my heart. After the teller cheerily handed me a crisp $20 bill and two ones, I added three more ones and put it all in a basket on the lobby table. The bank was collecting for breast cancer research, and I knew this was the only way I could enjoy my windfall, though I did snag one of the pink icing-covered doughnuts arranged around the basket.

In May 2016, I finally shed my skin. I sold my two shares for $210.48, after fees. During my 44 years as an independent stockholder, I made over $400 from an investment of about $30 (not adjusted for inflation). Not too shabby, but I have no feeling that I ever earned any of it. Shortly after I sold my shares, I read in The Guardian that The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was divesting itself of its entire $187 million dollar stake in British Petroleum as part of a move from fossil fuels.

I like to think, in some global vibe of the moment, that my little act of divestment had encouraged others. Certainly, I’m but a drop in the oil-soaked ocean, but then an ocean of such drops would dilute the disasters ahead.