Roughly, I support every secessionist movement anywhere. O hear my voice, people of the world! Independence for the Catalonians and Kurds, the Quebecois and the Flemings, the Scots and Chechens, Tibetans and Rohingyas, the Texans and the Northern Californians!

It’s obvious to some people that nation-states should be as large as possible, and the movement of history as they understand it demands bigger and bigger countries, Europe-sized countries, perhaps eventually a world-sized country. But I’m afraid you're going to need an argument.

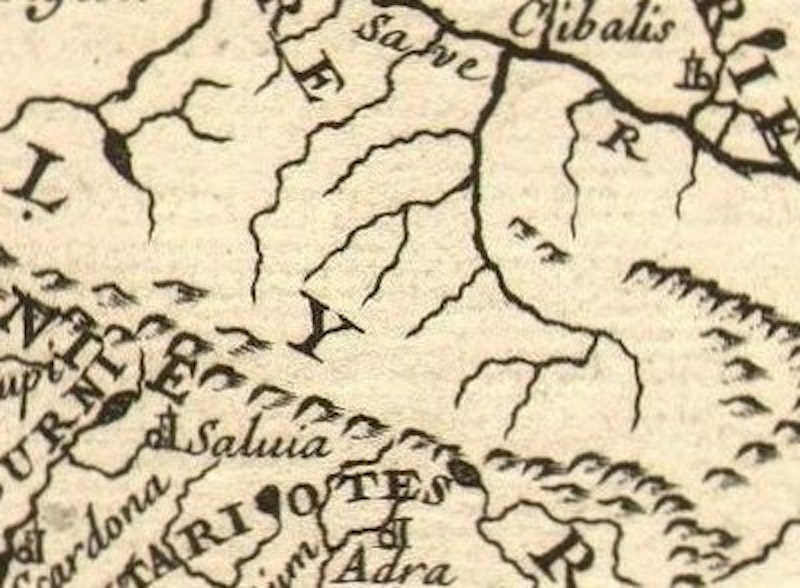

The nation-state idea is a mess. The concept is that people naturally fall into “nations,” perhaps characterized by common language, ethnicity, region, religious beliefs, or more amorphously a “culture.” Because of a shared set of values, these groups are natural political units that should each be organized internally as a separate state. It's often held that Europe was first clearly conceived this way by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, though it took a long time for some of the nation-states, such as Germany and Italy, to coalesce fully. Then the European powers, often ham-handedly, carved up the world on this model.

Really, the whole idea is a mess on every possible level, but what’s most conspicuous is its extreme ill fit to reality. Many nation-states imagine themselves to be unified culturally or linguistically, usually under the auspices of some dominant group. They take measures to simulate or coerce this sort of unity, repressing minority cultures or engaging in ethnic cleansing. To produce a unified national identity, they try to silence or expunge their own diverse elements. Watch Trump try that now. “America” is not some sort of natural cultural or even geographical unit, try as we might to produce one by saluting the flag.

This yields a situation in which Catalonia or Kurdistan are in one sense appealing to values that all the member states of the EU or UN recognize, abstractly: the right of “a people” to self-determination, and the naturalness of the nation-state formation as the expression of that. But all the member states also have a stake in pretending that the existing nation-states are inviolable. No government can endorse in any general way the legitimacy of secession movements in other states. But no government can explain clearly why it should be opposed on principle, because the appeal for autonomy rests on the same ideology that, for example, the U.S. does, or it rests on the basic conception of the nation-state.

There are, I admit, advantages to large-scale political units. People can move around without border guards and fences, sometimes. Large units may be more resilient economically in some ways, less subject to local problems or disasters. Sometimes, a situation with many small states is a situation of almost continual warfare, as in the Warring States period in China or in the wars that followed the Westphalian peace in Europe. On a very good day, a large state encompassing many distinct groups might succeed in producing some sort of unity among those groups, whereas if they each hunker down in their own state, they are likely to remain ignorant of and hostile toward one another. Of course, the actual historical record of nation-states integrating conflict-ridden populations is a mixed bag at very best.

And I see why, emerging from the world wars, which in some ways emerged from the conflict of the relatively little states of Europe, many people would associate large political units, and the EU in particular, with peace. And sometimes, for comprehensible reasons, the Cold War, which pitted two huge polities against one another and sought to split the world into just two forces, is compared favorably to those disasters. I’d ask you to take seriously that the two forces took military mobilization to unprecedented heights, and that they came very close on a number of occasions to destroying the entire world.

There are, as well, bad reasons to secede, for example so that you can continue to practice chattel slavery or religious persecution. Small nations can be brutal, oppressive and backward. But mega-states can also go wrong and, for example, mobilize into unprecedentedly huge killing machines, as in the forced collectivization of agriculture under Stalin or the Great Leap Forward of Mao. The United States and the Soviet Union strolled many countries all over the world into their war.

And whether it goes right or wrong, a large nation state is far away from responsiveness to any one of its people, or any small group of its people. The mechanisms of economic power operated by the EU, for example, are far away from the average student or worker in Athens. Size itself, beyond a certain point, is anti-democratic in the sense that each person's vote, or more widely each person's influence, is reduced proportionately. In a worse case, entire minority groups can be oppressed implacably, even in a system resting on democratic voting procedures. In the worst case, a gigantic, crushing, incurable bureaucracy bestrides a whole continent; against it, each person or group can only despair. I'm thinking about China, but also about America.

In such mega-states, the resources of whole regions flow toward the elite that controls state power. Money and power coalesce and assert control of whole hemispheres. There ensues a world oligopoly in the face of which any particular person or minority group or protest movement is puny and helpless. I think this is the narrative of the rise and expansion of the nation-state, and of the multi-national configurations that have emerged in the last century.

A “Balkanized” world of smaller nation states has been or would be a mess as well, and I’m opposed to borders as well as states, so it seems odd that I'd want more of them. But I think that the best shot we have of surviving is not ever-greater consolidation of power and resources, which will bring in their train ever-more systematic oppressions and ever-more wide-scale disasters. We need to keep politics more complex than that, more various, more local, more reflective of our differences as well as our commonalities.

Not that we're really going to get a choice in the matter, any more than the Kurds or the Catalans are getting.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell.