In 2014, when New York Times editor Sarah Jeong’s racist twitter posts surfaced, the paper unleashed a masterful display of rhetoric to justify not letting her go. No such luck for her colleague, Quinn Norton, who didn’t have the same professional and cultural cachet and immediately got the axe for some comparably awful tweets. Like most newspaper-cum-media platforms, the Times appeared to have drifted squarely into damage control, Twitter mob appeasement, and political fan service as a survival tactic. And it seemed to be working. Keeping Jeong on staff was part of it.

I was shocked they defended her. But that’s only because I hadn’t been paying attention. Having lived in the UK for years, I’d grown out of touch with how noxious US public discourse had become. I’d begun to assimilate different cultural sensibilities, which, even in the metastasizing identity politics of Obama’s second term, would’ve regarded Jeong’s open racism as unacceptable for someone at a major newspaper. Immersed in the hybrid expat mindset, no longer fully American but not quite English, I often felt bewildered by the social turmoil back home.

I asked an older UK journalist friend what he thought of the Jeong incident and the look he gave me seemed exhausted, amused, and ambivalent in equal measure. “She’s a flash in the pan,” he said. “Truly. Don’t let her occupy space in your head.” As if to say she was just another awful bullshit artist getting fleeting notoriety, another American media embarrassment. Looking back, I see how he was right. I also see how he was terribly wrong. Purveyors of scandal and outrage across the political-media spectrum would only get louder, more desperate, and more opportunistic with the Trump administration.

Jeong’s comments about white people only being fit to live underground, comparing white people to dogs, and crowing about how much she enjoyed being cruel to old white men are now barely memorable. And complaints about the Times indulging in blinkered activist journalism seem quaint, given the revisionist 1619 Project and Nikole Hannah-Jones’ declaration that she considers all journalism to be activism. After the tumult of the Trump years, we might be forgiven for feeling a little culturally desensitized and that we seem to have entered what Bret Easton Ellis, in his memoir, White, calls “post-Empire”:

If Empire was about the heroic American figure—solid, rooted in tradition, tactile and analog—then post-Empire was about people who were understood to be ephemeral right away; digital disposability doesn’t concern them—they’re rooted in traditions created by social media, which is solely about exhibition and surface, and they don’t follow a now dated path of artistic and cultural development. They’re about hypnotizing our attention for only as long as their loud bid can last, which is why they don’t adhere to conventional media pieties.

The lust for notoriety and press; the need to continuously generate shock, outrage, or approval; the commodification of human experience as clickbait continues because commentators, professional experts, politicians, and pundits really don’t have any reason to act better. This is their post-Empire mesocosmos, the media ecosystem in which they court attention at all costs. And they’ll do whatever it takes, capitalize on any tragedy, in order to be seen.

I was thinking about this and about the term, “flash in the pan,” yesterday while I browsed the inevitable “hot takes” on the resurgence of the Taliban. The sudden fall of Kabul is horrific, the full dimensions of which we haven’t yet begun to comprehend. It’s also a betrayal of the Afghan people and of those who gave their lives in a 20-year mission discarded overnight by an administration more interested in optics than anything else. What it shouldn’t be is an opportunity for more spin and ghoulish opportunism, but even the US government seems to be in a post-Empire fugue.

Anthony Blinken’s subsequent attempts at damage control would be funny if they weren’t an insult to human intelligence. But reality doesn’t matter. Human life doesn’t matter. Only “exhibition and surface” matters. And it’s from within that moral vacuum that we’ll witness the Taliban’s depravity when they drop their current façade and return to the usual parade of repression, torture, and decapitation.

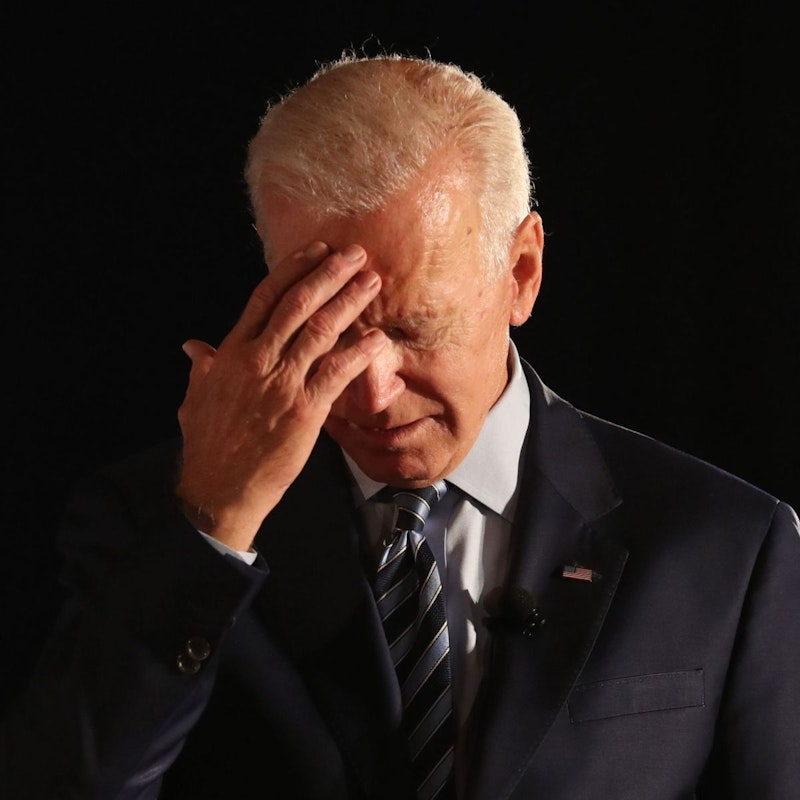

It makes little difference that Trump would probably have bolloxed the situation or that it was a losing scenario from the beginning. It makes little difference that Biden inherited the Afghanistan debacle from his predecessors or that shoddy intel contributed to a string of bad decisions. Even Biden doing nothing would’ve been preferable. As George Packer puts it in The Atlantic: “The Biden administration failed to heed the warnings on Afghanistan, failed to act with urgency—and its failure has left tens of thousands of Afghans to a terrible fate. This betrayal will live in infamy. The burden of shame falls on President Joe Biden.”

Packer is correct. The Biden administration’s desire to use the drawdown as a flamboyant public relations event only reminds the world how far the United States has strayed from the path of sound foreign policy into hollow reactivity and pretension, mistaking good press for politics.