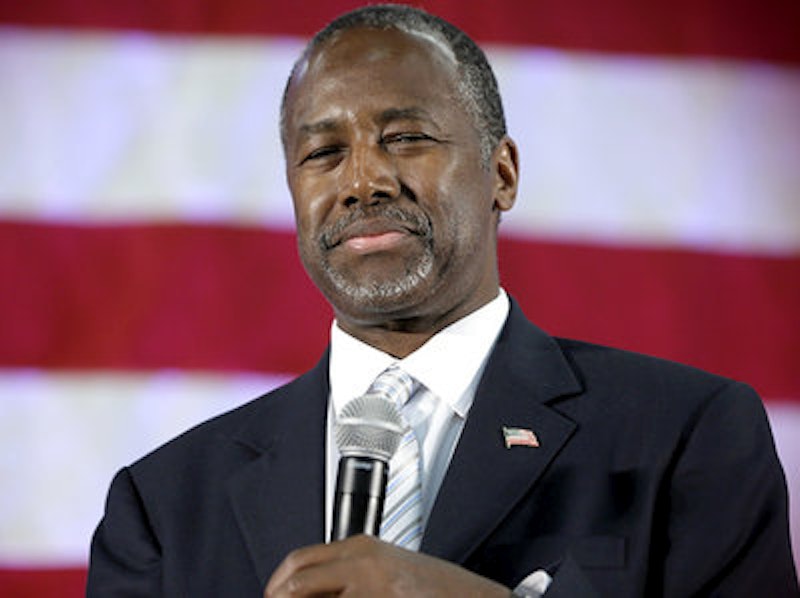

The first moment I laid eyes on Dr. Ben Carson he was mid-sentence, eyes wide and voice ringing clearly. He was at the podium in a packed Johns Hopkins University lecture hall where he was quickly winning over the crowd with a unique combination of science lecture and motivational speech.

This singular public memory of Carson is not a negative one. I still vividly remember a moment in which he explained, with total recall, the exact muscle, nerve pathway, and brain nuclei involved in the process of touching a neutral object as it becomes actually perceived. After he’d finished his two-minute description, the crowd erupted into roaring applause. All that remained was for Carson to begin levitating.

Carson didn’t do that, but it didn’t make him any less miraculous to the audience. Ostensibly Carson was there to discuss his life, a rise from poverty to celebrated neurosurgeon, and his side gig as a non-fiction writer. I don’t remember that part of his talk. After the initial intellectual magic trick, nothing else mattered. At 19, I was optimally geared to identify verifiable facts and balance a course load of disparate subjects with unhealthy vigor. Why should I have cared who Ben Carson was outside of his professional title? That he knew scientifically verified facts down to an astounding level of detail was enough.

After leaving the hall, I didn’t keep track of the doctor’s career. More than 10 years passed, and I was surprised to learn that he’d retired from neurosurgery and was running for president. That he’s running as a Republican doesn’t bother me. They say a lot of things during electioneering time which appear to be crazy, ill advised, or heartless but are ultimately delivered with a twinkle in their eye. On this front Carson hasn’t disappointed.

It’s not surprising that Donald Trump speaks like a boardroom bully. Jeb Bush is a chip off the unassuming but formidable Bush block. Carson had a tactful and deeply diplomatic public persona, he was a man who perhaps would speak about desires for reform, most likely medical, in some vague but substantive way. In the early stages, I found that my ideal of what Carson the candidate would think and act like was quickly challenged. Consider this October 2015 National Press Club transcript excerpt:

So what is it going to take to save our country? Courage. It’s going to take courage by all of us, including the press. And we have to begin to think about those who come behind us. Because what would have happened to us if those who preceded us were little chicken livers? What if they weren’t willing to take risk? What if on D-Day our soldiers invading the beaches of Normandy had seen their colleagues being cut down, 100 bodies laying in the sand, 1,000 bodies laying in the sand? What if they had been frightened and turned back? Well I guarantee you, they were frightened. But they didn’t turn back. They stepped over the bodies of their colleagues, knowing in many cases that they would never see their homeland or their loved ones again. And they stormed those Axis troops. And they took that beach, and they died. Why did they do that? They didn’t do it for themselves, they did it for you, and they did it for me.

This quote is not surprising or revealing. Every candidate has, at some point, fancied themselves a keen interpreter of the historical significance and re-teller of the gravitas of WWII. It’s been stated in many speeches that the country is something that deserves saving, though logically that perception hinges on the always volatile glass half full argument. Perhaps because of this volatility, preventing departures by candidates into too far left or too far right sides of rhetorical patriotism is most efficiently viewed as a bipartisan concern. Carson’s train of thought does not end with what would seem to be leading to a solemn moment of bipartisan silence.

And now it’s our turn. And what are we willing to do for our children and for our grandchildren? Are we willing to stand up? Or are we afraid that somebody is going to call us a nasty name, or that we’re going to get an IRS audit, or that somebody is going to mess with our job? You know, we have a lot less to lose than they did. And the people who were always telling me, ‘Hang in there, don’t let them get to you,’ believe me, do not worry about it, because the stakes are much too high.

—National Press Club transcript, October 2015.

Conjuring glory from the past is such standard protocol for presidential candidates that it’s a mild form of revisionism that is not pathological or damning. Nostalgia has at times served as a compelling and positive mandate to improve the future for the unfortunate who have survived armed conflict but remained scarred or did not profit from the conflict financially. In the manner of Machiavelli or perhaps more fittingly, the Marquis de Sade, Carson acknowledges that power can ultimately only serve as a reference to itself. This jives with the sentiment of tyrannical rule which views power as a paranoid preoccupation, the lessening of which can only results in its unthinkable and unbearable ceding; a sort of looming traumatic knowledge that the only thing worse than power is no power.

Outside of espousing personal philosophy, Carson’s words function brilliantly in speaking to both higher income and lower income Republicans. For the upper income bracket, evading taxes is a right, and so should be maintaining your livelihood through any means necessary. For the lower income bracket, he’s hinted at that deporting immigrant workers might remove unfair competition for low wage jobs. My problem with an early assessment of Carson the political candidate was not that I found his point of view on a past war immediate grounds for discrediting him. My concern is that his speaking about WWII as a reference point for how to view the optimum environment in which the average citizen proves their worth is a bit like someone enthusiastically stating that they understand how to dismantle and reassemble a sports car but don’t understand how a motor scooter works.

Maybe it was just rhetorical chest-beating that Carson felt he needed to show off in public. Surely he didn’t view daily life through the lens of a repeating cycle of crisis and heroic action. He was, after all, referencing a foreign event. I didn’t have to look far for his comments on domestic crisis. Following the October shooting at Umpqua Community College in Oregon, he expressed his view of what he would’ve done to the perpetrator had he been there as it unfolded. "Not only would I probably not cooperate with him, I would not just stand there and let him shoot me… I would say, 'Hey guys, everybody attack him. He may shoot me, but he can't get us all.'”

These comments uncannily echo and expand upon those made by the mayor of Inglis, Florida, the town that was the site of the 1000th mass murder since the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary. To me, Carson’s comments function at best to view him as having lived the part of the hero through books and movies second-hand or worse to cast extreme doubt over whether the man is a compassionate individual. His thoughts are on almost the same wavelength as those of another man who considered himself as infallible in acting at the moment of crisis, General Mireau of Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory. The character which Mireau was based on was a real man and though he may have valued his own life he didn’t value the lives of those he was supposed to guide safely to progress and victory. How do we know that? Because he demanded that his men march into certain death so that, should they unexpectedly succeed, he’d earn a promotion.

The Mireau paradigm is chilling, but it’s not difficult to logically accept. When you aren’t in a conflict yourself it’s easy to take the casualties as collateral damage. The typical protocol for politicians is to mask this ugly but true aspect of contextualizing unnatural death for the public. Carson seems to wholeheartedly embrace his uncensored and foul line of reasoning which places him in a league with despotic rulers more than it does reasonable men who’d attempt to protect citizens by entertaining negotiation or even retreat.

Acknowledging that you’d throw other men into a fire to prove your point is going too far. Carson is deluded by a sense of authority that borders on psychopathy. Many Americans want to see him in office, which is hard to understand. I know that for Ben Carson it’s clear that another person’s trauma, dead or alive, is only useful to him as a plank in his political platform.