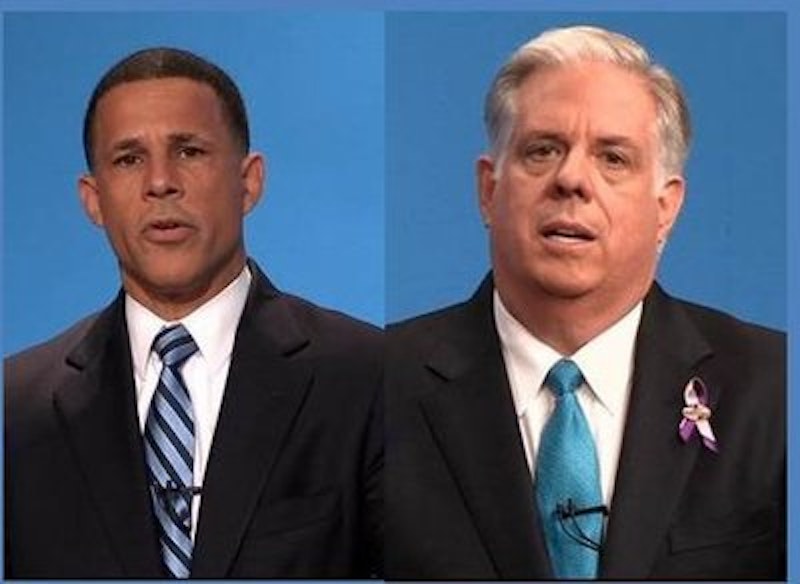

During the first of three scheduled debates, Brown issued a stunning manifesto: “There will be no new taxes in a Brown-Ulman Administration.” The damage was not the statement itself. The destructive force was that the voting public knows the pathetic utterance is baloney. The question now is whether Brown will repeat the claim in the remaining two debates—Monday, Oct. 13 and Saturday, Oct. 18—or back off. Either way he’s screwed.

A recent Washington Post survey found that taxes are the singular most important influence on Maryland voters’ minds, far ahead of education, jobs and health care. Implicit in that finding is the unavoidable conclusion that Republican candidate Larry Hogan’s relentless hammering at the O’Malley-Brown Administration’s cascade of tax increases (40, by Hogan’s count) has attached itself to the electorate’s memory circuits for future reference in the voting booth. Translation: Hogan has a far more effective campaign message than Brown.

When asked to elaborate on how he would manage the state’s uncertain finances, meet current obligations and fund future programs such as his vaunted pre-K program, Brown spoke vaguely in bureaucratese about finding savings in “vehicle fleet management,” appointing a study commission and re-asserting several times his newly found leitmotif of “we will not raise taxes.”

Brown also boasts of his involvement, as lieutenant governor, in forging public-private partnerships and his advocacy of such arrangements when, in fact, many such ventures in other states have been fiscal disasters with the states having to provide bail-outs.

For the lieutenant governor’s enlightenment, and as a handy voters’ guide for the remaining few weeks, herewith is a tutorial on government finance, some of it reprised from an earlier column on the subject, the self-plagiarism only because Brown has bumbled into making money and taxes an issue.

Two weeks ago, Comptroller Peter Franchot (D), who chairs the Board of Revenue Estimates, reported that Maryland faces another sinkhole of $405 million through lost income tax revenue because of stubborn job losses and unemployment. That comes on top of what has become a familiar refrain, another structural deficit of a couple of hundred million dollars. Structural deficits occur when revenue projections fall short of actual spending.

Brown’s attacks on Hogan’s proposed corporate tax cut notwithstanding, there probably will be some form of relief in the corporate tax rate (8.25 percent) and/or an adjustment in the taxes on limited liability corporations (LLC). Such a reduction would not only assuage the business community as well as be a visible gesture to improve Maryland’s business climate and its competitive position among surrounding states.

Hogan has proposed reducing the corporate tax rate to six percent. If Brown is elected governor, some form of corporate tax relief will be adopted even if over his objections, although after the election they would likely fade.

It is also a likely prospect that such a loss in revenue would be partially offset by the cherished dream in Annapolis of broadening taxes on services as well as the continued drive for federal approval of a state tax on all Internet sales. (Marylanders recently began paying sales taxes on Internet purchases from Amazon which has just opened a distribution center in East Baltimore.)

One way or another, the consuming public will help to pay for any corporate tax relief. That comes in addition to foreseeable increases in gas prices because of tax hikes that are now indexed to the sales tax as well as the flat tax per gallon.

The state’s share of the property tax, presently 11.2 cents per hundred, is the next big hike if Maryland wants to continue its construction program apace and still borrow money at low interest rates. Local governments rely on state money for school construction as well as subsidies to relieve pressure on local property taxes.

The state property tax is used mainly to pay off the debt on general obligation bonds which are used to finance building projects authorized by the state. That debt has increased substantially. Maryland now has the largest outstanding bond debt of any of the six Triple-A rated states in the nation.

Maryland’s bonded debt is nearly $10 billion and the state had just about reached its borrowing capacity. Continuing at the current property tax rate will make borrowing more expensive as interest rates on the debt load rise. Raising the property tax rate will increase bonding capacity as well as allow the refinancing of old bonds. The Board of Public Works—the governor, comptroller and treasurer—sets the state property tax rate annually every spring. Franchot estimates that an increase of about 7.7 cents is needed.

The three major bond rating houses, Moody’s, Fitch and Standard & Poors, receive more than $700,000 a year in fees from Maryland to help win the coveted Triple-A bond rating. The rating houses look beyond the state’s property tax rate, the traditional source of revenue to pay off bonded debt, for economic health and the ability to repay loans. To that end, they consider a variety of fiscal standards—balanced budget, outstanding debt, tax structure, reserve funds and other measures of economic good standing.

Operating the state of Maryland costs about $111 million a day, or $39 billion a year, close to $17 billion of those dollars in general state funds (mainly revenues from income and sales taxes) and the balance in special (fees, etc.) and federal funds.

The centerpiece of Brown’s campaign has been the expansion of pre-K to every eligible child in the state, the progressive cause du jour. Such a program would eventually cost nearly $300 million a year. Brown is mute on where the funds would come from.

On top of that, the biggest hit on the budget next year, no matter who is governor, will be in the area of education. It’s estimated that just to meet existing education obligations, the state will have to find an additional $700-$800 million. That figure is based on the conclusions of a new study of education funding “adequacy”—whatever that means.

None of the above includes the hundreds of millions of dollars that the administration of Gov. Martin O’Malley borrowed from special funds, such as the open space fund, to make ends meet during the economic downturn. Nor do they include the funds from O’Malley’s raid on the state pension fund, which he has pledged to repay in installments of $100 million a year.

O’Malley has repaid the money he borrowed from the state transportation fund which is required by law. (A constitutional amendment on the November ballot would create a “lock-box” on transportation funds which could only be borrowed in a formally declared emergency.)

The same Washington Post poll found that most voters believe that Brown’s agenda as governor would essentially be no different from that of his boss, O’Malley. The poll also revealed a growing disapproval of O’Malley’s job performance. Hence, what you see now is what you’d get later.

Brown’s insistence on an all-out pander of no new taxes is foolhardy politics and risky governance especially when everyone knows he’s shaving the truth. Brown’s been in the number two slot in government for nearly eight years and he should know the state’s fiscal condition better than most of us. And the one thing he no doubt learned is that tolls and fees can be raised and he can argue they’re not taxes. That’s another lesson he’d have to ignore because voters know better.