Two cases advancing through the courts could render Maryland and other states throwbacks to the era of poll taxes and property rights as conditions for voting and restore rural areas’ dominance over populous urban and suburban subdivisions in awarding congressional and legislative seats. One case is Maryland-bred and technical in nature; the other originates in Texas where voter suppression efforts are aggressive and commonplace.

Ocean City, the popular Maryland beach resort, was the state’s last town to require property ownership as a condition for voting until the city was pressured and the requirement was eliminated in a special election in the early 1960s. And the so-called unit vote, which gave rural counties geographic parity with densely populated cities and counties, was also outlawed in the 60s by the Supreme Court’s “one man, one vote” ruling. That ruling is now being challenged in the very same court but with a different makeup.

The two cases arrive at a time when the method of representation—congressional and inherently legislative redistricting and the bodysnatching involved in awarding seats—is being challenged across the country for its inventive but thoroughly legal way of divvying up population to gain political advantage. Those who complain are either losers in the jigsaw of redistricting or others who demand purity in the process no matter what the outcome.

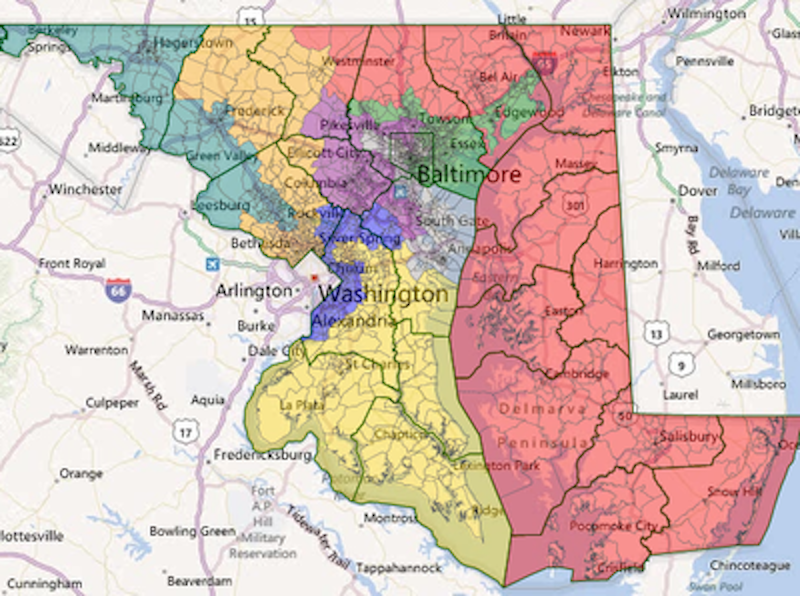

For Maryland, the cases come forward at a beneficial time for discussion—the gathering of legislators for the 2016 General Assembly session, and the initial report of Republican Gov. Larry Hogan’s study commission on redistricting which stated that Maryland’s process is a partisan farce in a two-one Democratic state while others have called the state’s congressional map among the most gerrymandered in the country. Not to mention that 26 Republican-controlled states have carried out the same partisan preemptive map-making to their benefit.

Maryland’s Democratic legislative leaders are also reported to be considering a universal voter registration system that would automatically enroll every eligible voter and would offer with it the choice of opting out. Two other states, Oregon and California, have automatic voter registration. So what one decision would give the other would take.

The Maryland court case, Shapiro vs. McManus, turns more on free speech and the right to be heard than on redistricting itself. Essentially, the Supreme Court ruled that a federal judge goofed by dismissing the lawsuit unilaterally rather than allowing it to be heard by a three-judge panel. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld the lower court decision, according to reports. So essentially the Supreme Court said the case should be re-heard.

The suit was filed by Steve Shapiro, a gadfly from Montgomery County who’s so obsessed with Maryland’s manic redistricting process that he quit his federal job to attend law school. Kennedy’s novel argument holds that redistricting, as it is applied, favors one group of voters over another because of their political views.

Under the present arrangement, Democrats hold a seven-one advantage in congressional seats in a state where Democrats outnumber Republicans by more than two-one. The configuration and physical shape of Maryland has much to do with the curious alignment of congressional districts. It makes gerrymandering’s sleight-of-hand more contorted and obvious.

The only existing guideline for congressional redistricting is population balance. Each of the nation’s 435 districts must contain approximately the same number of people, currently about 625,000. Racial gerrymandering is the only exception wherein the courts have allowed the bleaching of certain districts to pack other districts with blacks to create minority representation. The number of districts, 435, is set by law while population shifts are considered every 10 years. Some states gain representation while others lose.

To illustrate the population disparity, there are seven states with a single member of Congress: Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont and Wyoming. By contrast, California has the most members of Congress with 53 and, interestingly, Texas is second with 32.

The Texas case is more far-reaching and insidious. It’s a continuation of the state’s efforts to undermine minority and other classes of voters. It would draw congressional district boundaries based solely on registered voters and not—as is now the case under the “one man, one vote” ruling—on overall population.

Texas has been among the most aggressive states in attempting to suppress voting. Texas, too, has been involved in a number of challenges over redistricting, most notably when Rep. Tom Delay, the convicted House minority leader, dominated the process. The DeLay plan was rejected by the courts. And on another occasion, more than 50 Texas Democratic lawmakers fled the state rather than vote on an outrageously gerrymandered Republican plan.

This case would eliminate from the 10-year head-count on which congressional districts are drawn those who are least likely to be registered voters—minorities, undocumented aliens, the poor, the elderly and the young, those most likely to live in populated urban areas. The last attempt by Texas to abuse voting rights occurred when the state not only required photo IDs but also limited their availability to locations that were so inconvenient that the marginally affected were unlikely to obtain them.

The Texas case was filed by two rural residents who claim their areas contain far more eligible voters than some urban areas, according to reports, and therefore their votes are diluted. But House districts are based solely on population and their proposal would exclude children and others who are ineligible to vote. Moreover, many federal aid formulas are based on population within congressional districts and that alone could have a devastating effect on districts and population centers across the country.

But the singular effect of the Texas claim would be to eliminate the “one man, one vote” principle and restore the repudiated unit rule. Percentages of votes would replace actual people and give greater representation to rural areas, which tend to be Republican, than to urban or suburban areas, which are likely Democrat.

In Maryland, for example, Garrett County, at the western margin of the state adjoining Pennsylvania, might have a higher percentage of registered voters than, say, Baltimore City, which has at least 10 times the population of Garrett County. (A classic application of the unit rule, combined with a quaint custom called “local courtesy,” occurred in the Maryland General Assembly in 1963 when the state’s nine Eastern Shore counties exempted themselves from the public accommodations law.)

In Baltimore there are roughly 355,000 registered voters (324,000 Democrats and 31,000 Republicans) out of a total population of 619,000—a notch more than 50 percent. Under the Texas formula, nearly 50 percent of the city’s population would not be considered in the formulation of the state’s congressional districts, costing the city power in Congress, representation in Annapolis and hundreds of millions in formulaic aid funds—exactly what conservatives want.

There are many reasons in urban areas why people don’t register to vote—undocumented aliens, newly released convicts, avoiding jury duty (potential jurors’ names are picked from voter rolls) and dodging civic engagement for one reason or another. This case could be one more.