Despicable as Alger Hiss was, I have to admire the way he brazened it out to the end, leaving us with just that tiny pinhole of doubt about his guilt. I'm always on the lookout for solid, persuasive arguments in Alger's defense. I keep abreast of new books on the Hissiana shelf but they’re a pathetic lot. The last one of any note came out a couple of years ago, and it's derivative, cliché-ridden dross by an old lady who very much wants you to know she met Alger, didn’t care for him, but now thinks he was hard done by—because of Nixon! (America’s Dreyfus: the Case Nixon Rigged, by Joan Brady.)

There's also a tidy, well-maintained website called The Alger Hiss Story, and it's an order of magnitude better than any pro-Alger book. Alas, it's evasive and madly biased, recycling every slur against Whittaker Chambers and Richard Nixon, as well as rehashing all the 1950s pinwheel theories about the Woodstock typewriter, and how the Hiss Case was a conspiracy to discredit the shining legacy of the New Deal.

I remain open to persuasion, but I need to see a better brief. I imagine it would include a fresh and exciting story about what Whittaker Chambers was really up to in the 1930s, when he was supposedly an underground Stalinist operative in New York, Baltimore, and DC. (Chambers' vague, sonorous version in Witness, later expanded upon by Allen Weinstein and Sam Tanenhaus, leaves too many questions unanswered.)

The re-telling ought to concede that Hiss moved in pro-Red circles, along with Harry Dexter White, Lawrence Duggan and many, many others; while arguing that Alger was small potatoes in the grand scheme of things, nowhere near the subversive level of a Harry Hopkins or Henry Wallace. (The White House and FBI were aware of Hiss' doings by 1940, but weren't particularly bothered.) The story might argue that Alger was a sacrificial victim who got thrown out of the troika as distraction.

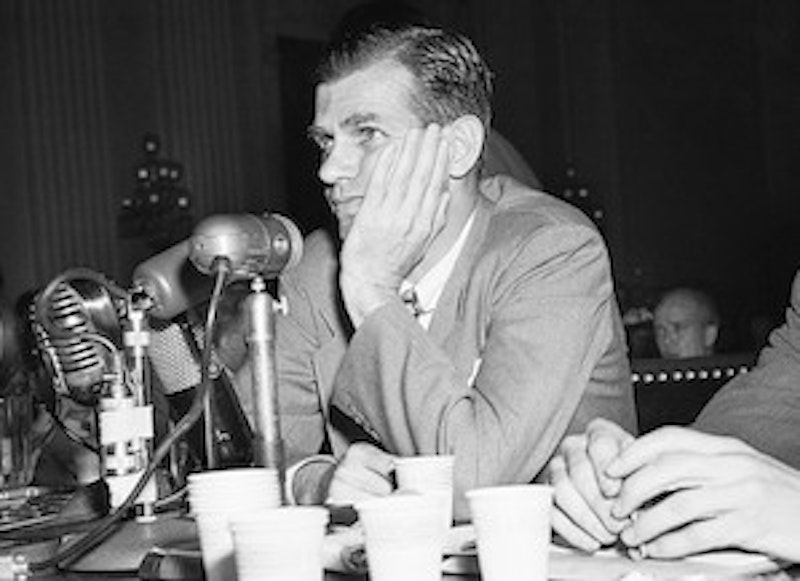

He was expendable, an egotistical nitwit who could screw up a two-car funeral. Instead of lying low and going Pshaw! when Chambers' accusations became public, Alger insisted on testifying to HUAC and confronting Chambers. There was no need for this. He hadn’t been subpoenaed; he had a posh private-sector job as head of the Carnegie Endowment, and looked far more credible than the shifty-looking Chambers, who seemed to change his story at every turn. But then, bless us all, Alger went and shot himself in the other foot by suing Chambers for defamation, setting in train the whole process of discovery and court trials. Had the erudite Hiss never heard of Oscar Wilde? Perhaps not. Per Chambers, Alger was distinctly unliterary.

This, I think, would be an effective apologia for Alger Hiss, though I don't think I could sell it to hard-core Hissies. I've run into a number of them in my life, and have usually enjoyed talking to them. They're getting thin on the ground now, dying off. Some were actual Commies back in the 1940s and 50s, others were red-diaper babies who learned the pro-Hiss catechism at their mother's breast. Their double-speak is always the same: Hiss was slandered, Hiss was framed, Hiss was a victim of Nixon, the FBI and witch hunts! But they admire him greatly as a political martyr, because, you know—wink-wink—he was one of us. You never see Adlai Stevenson fans playing this game; Hissies are almost always doctrinaire Old Lefties.

In 1990 I briefly shared a semi-private room in St. Vincent's Hospital with a huge 70-year-old redhead named Elinor Ferry. I don't remember how the Hiss-Chambers case came up in conversation, but ineluctably it appeared, like King Charles' head. Elinor was off and running: "He was innocent, you know. The FBI framed him! I've seen all the files. I did research for his appeal."

Years later I verified this last bit. Our Elinor, who died a few years later, devoted much of her adult life to "vindicating" Hiss. She'd collected, read, boxed up every shred of available testimony, FOIA files, court transcripts, and personal interviews. A beatific look came upon her face as she bragged about the boxes and boxes of documents she'd collected over the years. She spoke as though she believed there was a crucial scrap of evidence still out there... hard, definitive proof that the FBI contrived evidence which when revealed would prove Hiss an innocent man.

It now occurs to me that Alger himself was still very much alive at this point, a few minutes' walk from our hospital room, in fact. Surely, if there were any smoking-gun letter or forged evidence that would prove his innocence, Alger would already know about it. He didn't need this big old redhead fossicking around.

Elinor was typical of most Hissies I've known, in her unending devotion to Alger, in her political affiliations (she was married to the publisher of The Nation at one point), and in her cognitive dissonance. Hiss had to be innocent of being a Red spy, because he was a good guy, a hard-core Lefty: ergo, a victim of a right-wing Red Hunt. Hissies have this little mind-trick whereby they shift the focus of the issue from Alger being a Commie spy to the likelihood that the FBI and prosecution framed him. As though that really mattered. I mean, if you stumble into being the defendant in a high-profile case, shouldn’t you sort of expect the prosecution to stack and jigger the evidence?

Decades ago the Hissies liked to misdirect you by talking about the Woodstock typewriter, the machine that Hiss and his wife supposedly used to copy State Department communiqués. They’d tell you, "The typewriter was a fake, the FBI had it manufactured, the Hiss people proved this later on by building a fake typewriter themselves..." Which may or may not be true, but it's beside the point. What convicted Hiss was document comparison, not the physical existence of this or that typewriter.

In later years the Hissies grasped at thinner and thinner straws, such as getting an old KGB general to say he couldn't find any Alger Hiss stuff in his files. Finally there's the old standby technique of ignoring the facts altogether and saying Alger was just a nice old man, why would anyone be mean to him? Alger's son, the writer Tony Hiss, has pretty much built a career doing this.

It would be really swell if a bunch of secrets just tumbled out of a ceiling someday, and it turned out that Hiss wasn't a Commie spy after all, he was just what he always came across as—a dim prig with a broomstick up his ass. The sort of brown-noser who does well at Harvard Law, clerks for the senescent Oliver Wendell Holmes, and then moves on to a series of sinecures with the State Department, the UN, and private foundations. This is certainly the picture you get from Hiss himself. In the mid-50s, after prison, he wrote an apologia called In the Court of Public Opinion, and it’s dreadful, a bloodless legal brief arguing that the evidence in his case was insufficient. People came to the book expecting a story of heartbreak, anger and confusion, something like: "I guess I've known some Communists over the years, and some were good people; but I wasn't one myself, and I don't know why anyone would want to tar me with that brush."

Instead he gave us legal quibbles and close-up photos of typewriter keys. Here he had legions of supporters, active and potential, and he let them all down by acting like a guilty, weasely, lawyer.