The speakers all got along. “What he said made absolutely perfect sense,” Newt Gingrich said of Rick Perry, a wonderfully considerate piece of phrasing given the mess Perry is in after his notorious list-of-two gaffe. Gingrich batted down a chance to attack Mitt Romney, “a friend who’s a great business manager” and “a good manager” and “an enormous improvement over Barack Obama.” At one point Jon Huntsman spunkily corrected Romney: “First of all, I don’t think, Mitt, you can take China to the WTO on currency-related issues.” But it was a Niles and Frasier moment, like he was reminding Romney of a rule in a board game.

CBS hosted with the National Journal, but cut away when the debate still had half an hour or so to go. This was by pre-arrangement. Nothing pressing had occurred; a rerun of NCIS went on. The debate was billed as “The Commander-in-Chief Debate,” an august sort of name. Yet the show was manhandled by the schedulers. Foreign policy may be august, still, but possibly it’s not as important to viewers as it used to be. The Commander set looked barebones next to the one for the economy debate.

Commander-in-chief. Asked about the Anwar al-Awlaki killing, Romney firmed his jaw and belted out a foreign policy credo: “An American century means the century where America leads the free world and the free world leads the entire world.” He said President Obama doesn’t understand this. At the same time, Romney said he thought Obama was right to have al-Awlaki, an American, assassinated. The connection didn’t make sense, but Romney was seizing his commander-in-chief moment, and he handled it well and at length.

Others looked for their commander-in-chief moments here and there. Herman Cain was handicapped in his attempts by a tendency to dwell on how he would consult with the people who knew things. He began working through the steps in a grouchy, halting way, as if a roomful of schoolchildren needed reminding about life’s basics on a slushy winter morning when his cold medicine was killing him. “You will know you’re makin‘ the right decision when you consider all the facts and ask them for alternatives,” he said.

Huntsman managed a beauty of an aria when the panel was asked what it would do if some nukes were hijacked. The question was not addressed to Huntsman; he had to nip in and grab it after being asked about the Euro. “The—let me just—on Pakistan for one second,” he said. A transcript notes “(clears throat).” Then: “Because it’s pretty clear.” This was followed by a bravura run of savvyness: “one man in charge in Pakistan ... negotiated with the Pakistanis before … a tough bunch … pick up the phone and call Special Operations Command in Tampa.” He told us what he would say into the phone: “I’ve got a job for SEAL, SEAL team number six. Prepare to move.”

The Romney commander moment looked pale next to Huntsman’s. Romney had made a good effort, but it was still just a statement of principles drafted so he could flex his chin. Huntsman pulled his spiel together right on the spot, like a magician whipping a balloon-animal into existence, and he sounded not just resolute but hands-on. It was an odd effect for the kid with the silver cheekbones, but he pulled it off. All Romney managed was resolute.

Beliefs. Cain said he was absolutely against torture and would abide by what the “military leaders” tell him is torture and what isn’t. He’s sure, though, that water boarding isn’t torture. Michele Bachmann said she thought waterboarding was fine. Huntsman said he was against torture, flat out, and received a good hand for it. He had a clever argument, pointing to America’s unique selling appeal to foreigners. “We have a name brand in the world,” he said. With torture, he argued, “We dilute ourselves down like a whole lot of other countries.” Ron Paul was even more against torture and received the biggest applause of a quiet night.

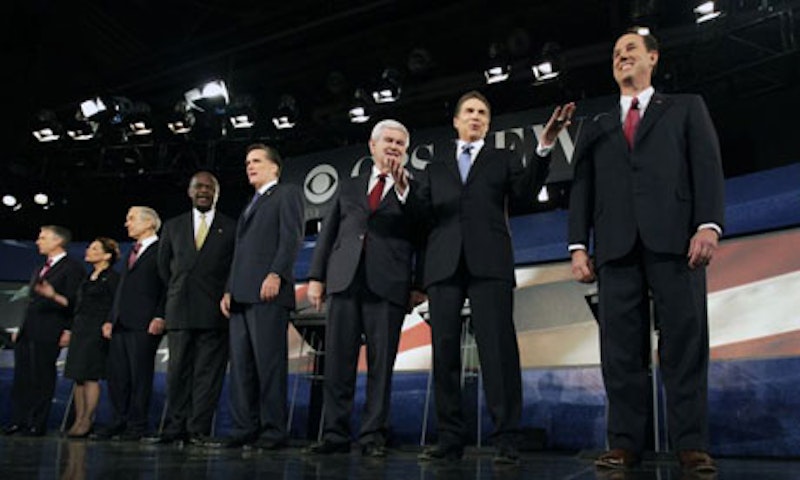

The set. It was like an out-of-focus schoolroom, with an enlarged bulletin board behind the panelists. Their podiums, seen straight on, looked like stools that the candidates held in front of them. But at least you could see where this set was located: a college auditorium (of Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C.). Visually, it’s still hard for me to place where the economy debate took place. The papers said Detroit, but to look at the setting appeared to be a light show that had half-taken solid form. It was the same sort of environment as you find on X-Factor, the familiar trans-dimensional warp place created by TV-event set design.

Perry’s moment. Rick Perry took a question about Pakistan and turned it into a chance to proclaim that he’s the candidate who will cut all foreign aid. That’s a good product feature to have, going zero on foreign aid, and at the end of his response Perry managed to wade back to the original question and say that Pakistan, for sure, would be getting no foreign aid. He said it to applause. Gingrich patted the governor on the head and then restated the man’s views but far more tersely and fluently. Gingrich even deposited a neatly wrapped piece of ironic understatement at the end: “I think that’s a pretty good idea to start at zero and sometimes stay there.” That was how he got across the threat to Pakistan’s aid.

Newt Gingrich just likes to talk. Gingrich’s debate reviews have been good and his polls are in the mid-teens. Pre-debate press speculated on whether he’d mount some sort of power drive against Romney, a grab for authority. He didn’t. Gingrich has come into his own, but for him this appears to mean holding forth and nothing but. At the South Carolina debate, he periodically sprayed generosity about him, and then went back to being the stage’s dominant mouth.

If he brushes anyone back, it’s by preening. That is, he may put on a certain remote air of intellectual inspection while taking up and considering another candidate’s idea. He may even inflect this air with a pronounced little tinge of bafflement. Gingrich’s tiny change purse of a mouth is more expressive than it has a right to be. He has a way of lifting his turtle chin so that the tendons stretch between his shoulders and mouth. Incredibly, this expression is effective. You see an accomplished, assured intellect that can unknot involved matters and slice away imaginary difficulties.

Gingrich’s flair for simulating authority allows him to shrug off stage pitfalls. Tim Pawlenty was destroyed when he tried out his “Obamneycare” crack on Fox and then flinched from using it in the next debate. On Saturday a moderator invited Gingrich to repeat what he had recently said on the radio, namely that Romney was a manager and not a change agent. Gingrich brushed him off. “I brought it up yesterday ’cause I was on a national radio show,” he said, as if the moderator had tripped over intellectual ground rules that everyone else knew about. Where Pawlenty shriveled, Gingrich made it seem like he was schooling the media.

Republicans say Gingrich was a mess back when he ran the House, that chaotic time in the mid-90s. He was a whiner, a blabbermouth, a fumbler, a mark. He had no sense and a tendency to emote during crisis, and was continually outfoxed by Bill Clinton. The GOP caucus booted him as speaker in 1998, and ever since then he has been a mouth on top of a body. This state suits him just fine. He is a performing miracle of the modern age, a virtuoso spouter of opinions ready for digestion by small audiences. The audience can be in a college auditorium or watching TV in the living room, but Gingrich is like Mick Jagger working a London club years ago.

Presidential debates have been a standard feature of elections for more than 40 years. Like any form, it can become an end in itself. Debates are supposed to identify plausible presidents. But Gingrich is easily the squad’s best debater without being anyone’s idea of a president. For now this appears to satisfy him and everyone up there with him.