Gates has a compelling point — largely because the shortage of Americans holding or pursuing advanced degrees in fields like computer science defies conventional market explanations. The average annual salary in the field is more than $100,000. Meanwhile, we have a robust supply of high-IQ baristas and college graduates with jobs that a generation ago would not even have required a high-school diploma.

Students respond more profoundly to cultural imperatives than to market forces. In the United States, students are insulated from the commercial market's demand for their knowledge and skills. That market lies a long way off — often too far to see. But they are not insulated one bit from the worldview promoted by their teachers, textbooks, and entertainment. From those sources, students pick up attitudes, motivations, and a lively sense of what life is about. School has always been as much about learning the ropes as it is about learning the rotes. We do, however, have some new ropes, and they aren't very science-friendly. Rather, they lead students who look upon the difficulties of pursuing science to ask, "Why bother?"

A century ago, Max Weber wrote of "Science as a Vocation," and, indeed, students need to feel something like a calling for science to surmount the numerous obstacles on the way to an advanced degree.

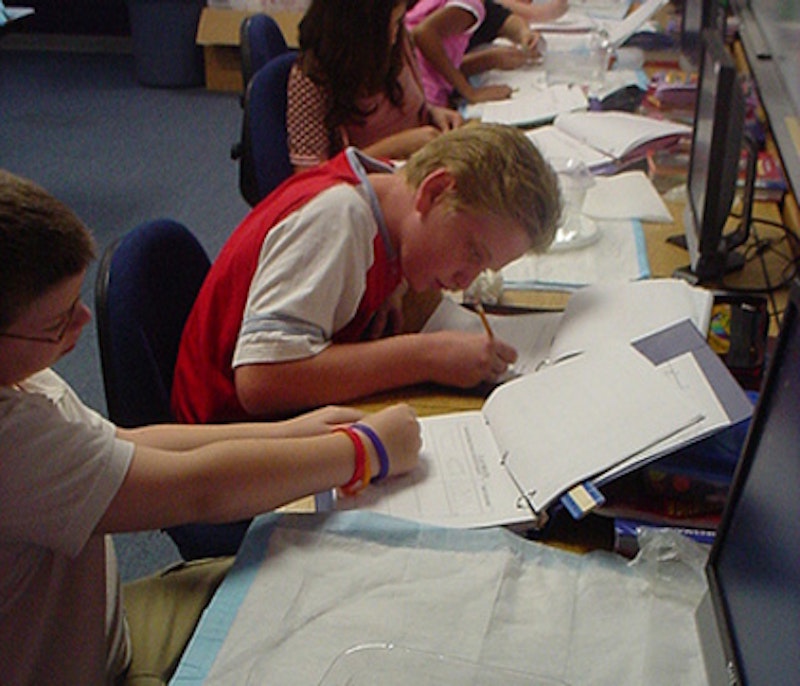

At least on the emotional level, contemporary American education sides with the obstacles. It begins by treating children as psychologically fragile beings who will fail to learn — and worse, fail to develop as "whole persons" — if not constantly praised. The self-esteem movement may have its merits, but preparing students for arduous intellectual ascents aren't among them. What the movement most commonly yields is a surfeit of college freshmen who "feel good" about themselves for no discernible reason and who grossly overrate their meager attainments.

A society that worries itself about which chromosomes scientists have isn't a society that takes science education seriously. In 1900 the mathematician David Hilbert famously drew up a list of 23 unsolved problems in mathematics; 18 have now been solved. Hilbert has also bequeathed us a way of thinking about mathematics and the sciences as a to-do list of intellectual challenges. Notably, Hilbert didn't write down problem No. 24: "Make sure half the preceding 23 problems are solved by female mathematicians."