This past academic year has been rife with discussion of sexual assault, especially on campus. I’m cautiously optimistic that we’ve turned a corner, that victims of sexual violence are more likely to be believed and see justice than ever before. Of course, that can only happen if we—feminist writers like myself—don’t blow it.

It’s likely that the biggest rape-on-campus story of this past year is one that didn’t happen. In the now-infamous debunked and retracted story published in Rolling Stone, a junior named Jackie claimed to have been brutally gang-raped in a fraternity hazing ritual at the University of Virginia. After questions raised by journalists like Worth’s Richard Bradley and Reason’s Robby Soave, deeper research done by the Washington Post, a police investigation by local authorities, and a report by the Columbia School of Journalism, Jackie’s story was found to be not true. The story’s author, Sabrina Rubin Erdely, failed in her due diligence as a reporter, to the point of being accused of fabricating quotes. In addition, the Columbia report also accused Rolling Stone’s editorial staff and fact-checking department of neglect. I’d compare their level of neglect to leaving a puppy in a locked car in the Miami sun.

A story as explosive as Jackie’s was bound to go viral, especially in the feminist corner of the Internet. Bradley was dead-on in his description of the article as being loaded with “[confirmation] biases… this story nourishes a lot of them: biases against fraternities, against men, against the South… pre-existing beliefs about the prevalence—indeed, the existence—of rape culture; extant suspicions about the hostility of university bureaucracies to sexual assault complaints that can produce unflattering publicity.”

In the months following the unraveling of Jackie’s story, it’s been interesting to observe a certain level of bias, and even denial, in the realms of feminist commentary. Not just in regard to Jackie’s story, but also in other high profile cases of campus assault.

There is, I believe, legitimate concern that the fallout from Erdely’s bad reporting will result in future rape victims being met with greater scrutiny. That said, the extreme measure of blind belief demanded by feminist commentators like Zerlina Maxwell is absurd. At The Washington Post, Maxwell writes, “We should believe, as a matter of default, what an accuser says. Ultimately, the costs of wrongly disbelieving a survivor far outweigh the costs of calling someone a rapist.” While Maxwell goes on to say this shouldn’t be applied to the legal system, she forgets that healthy skepticism is a necessary part of journalism. Jessica Valenti makes a similar argument in The Guardian, accusing Rolling Stone's staff of victim-blaming, when they were actually trying to deflect blame onto Jackie for their own irresponsibility.

Once it was established that the crime never took place, the usual discussion of “victim-blaming” should’ve stopped. In fact, I think feminists need to take ownership of the discussion of women who make false rape accusations and research the phenomenon rather than their current talking point of shrugging it off. Most of what I’ve been able to find on the topic tends to take me into the world of men’s rights activism, and I wouldn’t describe much of what goes on there as legitimate human rights activism so much as anti-feminist contrarianism. From the minuscule amount that we know about Jackie, and from what I learned about Crystal Mangum (the woman behind the Duke Lacrosse scandal), I wouldn’t describe women who make false rape accusations as mentally healthy. In the age of social media, one false accusation, that might have been a local anomaly a decade ago, can now travel the world in a day. This digital paper trail can create the perception that false accusations are more common than they actually are. Feminist writers need to brace themselves for that eventuality.

As Rolling Stone’s campus rape story was coming undone, Columbia University student Emma Sulkowicz was emerging as a willing patron saint of campus rape victims. She alleged she was raped by friend and fellow student, Paul Nungesser, in her sophomore year, who was not held responsible by Columbia’s disciplinary board. She made it her senior project to carry her mattress everywhere, symbolizing the burden that victims carry with them. She said she’d carry her mattress until graduation, or until her alleged rapist was expelled—whichever came first.

In all of the feminist cheerleading that surrounded her case, the rights of the accused were overlooked. He wasn’t held accountable by Columbia, and when Sulkowicz filed police charges, they were dropped due to lack of evidence. Unlike Jackie’s case, Sulkowicz’s looked more like typical acquaintance rape, mired in the he said/she said muck. There were no witnesses, and no physical evidence because the first reports weren’t made until about two months after the alleged attack. I’m actually amazed, from a legal standpoint, that Sulkowicz was allowed to embark on the project for full credit. So was Nungesser, who told his version to Cathy Young at the Daily Beast, and has gone on to sue the school for endorsing a campaign of harassment against him.

Over at Jezebel, the response was to shoot the messenger. In Young’s previous work, she’s been critical of how anti-rape activists use data and defensive of those accused of sexual assault. So Erin Gloria Ryan described her as “reliably rape-skeptical,” treated Sulkowicz’s accusations like absolute facts, and neglected the fact that Nungesser has the right publicly defend himself when he has been publicly accused of rape. At Raw Story, Amanda Marcotte described Young’s article as an “evidence-free insinuation-fest.” Despite her citations, I came away wondering if Marcotte and I read the same article.

Personally, I think that Sulkowicz’s accusations have some credibility. It has more to do with the fact that he’s been accused of assault by two other women and one man. One of the women, who is choosing to remain anonymous, did manage to get Columbia to hold Nungesser responsible for groping her (this was overturned on appeal, largely because she was already finished with school, and couldn’t take time away from work to respond). Only Sulkowicz has accused him of rape, but for me, this is enough to show that Nungesser doesn’t seem very good at respecting people’s personal space. And that’s all the belief I feel I can give her.

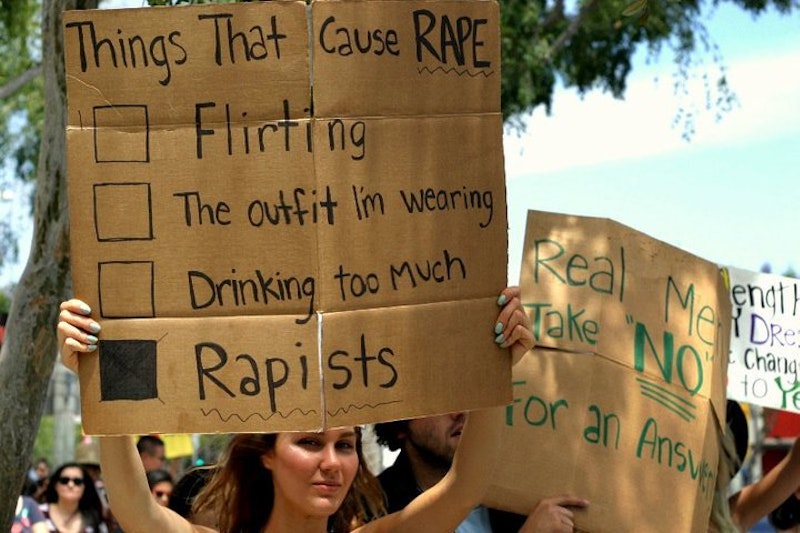

If I think that the commentary around feminist discussion of rape on campus is flawed, it’s because the discussion has become dumbed-down and short-sighted. In the growing movement for rape victims to be believed, they treat the demand for proof like an intrusion. I think the blasé attitude surrounding legal protocols is actually creating disinformation. Too many people don’t know what to do when they’ve been assaulted, and still too many don’t feel safe to go to the hospital or the police when they do. I also think the emphasis on the rape of women on campus should be broadened to include the rape of every person in every place.

In a recent debate at Brown University, independent feminist and anarchist Wendy McElroy presented an interesting takedown of everything that’s wrong with the conversation about rape on campus. In answer to the evening’s question of how colleges handle sexual assault she said, “It’s a criminal offence, go to the police. Rape is a crime! It’s not an infraction of college policy. They’re trained to investigate and process it, and they usually, often, maybe… they do a piss poor job. I don’t argue with that. But I think they do a better job than bureaucrats [and] academics… If students want to make a difference, in the justice with which rape victims with are treated, then they should be protesting at police departments and outside courtrooms. If you did that, and you changed the efficiency and the attitudes with which law enforcement approached rape, then you would be helping just yourselves. You’d be helping every woman in America. Every woman would be in your debt.”