I’m taking all the Trump-Sanders match-ups with a grain of salt right now—it’s February after all, although the angst of #NeverTrumpers like Max Boot (who says he’ll pick the “poison” of Sanders over Trump; he’s a charity columnist for the “Give the Elites a Bigger Say” Washington Post) is entertaining—but do think Bernie’s politically dodgy remarks about Castro and Cuba might dog him throughout the campaign. Maybe not, it could be, like so many other “news” events, a two- or three-day story, but when the Democratic frontrunner said, “When Fidel Castro came into office,” my ears perked up. One of my sons, a Sanders supporter, told me that no one under 45 (if they vote) “cares about Castro,” and that could be, but I’m sure older Democrats did a double-take, and as for Florida, it’s hard to see how Sanders could win there. That’s a problem for Democrats: if Trump can’t take Florida, he’ll lose.

Not surprisingly, The Wall Street Journal editorialized on Tuesday: “Cuba has gone from being one of the more advanced countries in the region in the mid-1950s to one of the most impoverished, and the reason is its economic socialism and political tyranny. The issue for voters today is what it says about Mr. Sanders that, even after so many years of cruel evidence, he still feels compelled to insist there is a silver lining in the Cuban revolution.”

Anyway, all of this reminded me of a man who was my teacher for the fifth and sixth grades in Huntington, New York. Howard Shapiro (name changed to spare his descendants any embarrassment), who was probably about 35 at the time (1966-67), wasn’t a typical public school teacher, for better and worse. Were he alive, he’d be a vociferous Bernie graybeard, the Senator’s comments on Israel notwithstanding. The fact that I even remember his name is testament that he wasn’t one of those dull, suburban clock-watchers who led most of my classes. (That’s not a knock on Huntington’s public schools decades ago; my four brothers and I received a quality education.)

Mr. Shapiro was a bear of a man, overweight with a Mitch Miller-like goatee, and wore a black suit and black tie every day, sort of like an undertaker. Each morning he had a quart of milk on his desk, the remedy for an ulcer condition. On occasion, he’d send one of the boys down to the cafeteria for a pint if he needed reinforcement. Academically, Mr. Shapiro wasn’t a slouch; he was proficient in what was then called the “new math,” science, English and history, but if any of his students were so inspired by him that the course of their lives were altered dramatically, I’d be very surprised. He was a smart man who, along the way, got sidetracked. I suspect he led a life of disappointment.

What separated Mr. Shapiro from the rest of the pack was his personality, which might be charming one day, but then vicious the next. Today, I’m sure he’d be popping anti-depressants instead of gulping milk, but the man had a presence. For example, in November of 1966, the day after the midterm elections, the class settled in at 8:30 and Mr. Shapiro gravely announced, after The Pledge of Allegiance, “This is a day of infamy for the United States. An actor will be governor of California!” A New Deal Democrat, the thought of Ronald Reagan in office turned his already-tortured stomach. On that day in ’66, he was in a very foul mood and so distressed that he allowed the 30 or so students to read or talk quietly until after lunch, when, ostensibly, he was better able to cope.

On the other hand, when payday hit every other Friday, he’d often surprise the students with bags of gum drops, chocolate-covered peanuts and raisins, jelly beans and Tootsie Rolls, distributed evenly on each desk when we’d come back from afternoon recess, about an hour before the 3:00 bell rang. And sometimes he’d talk about the Holocaust, not in an especially melodramatic way, but explaining how, as a Jew, his extended family had suffered, and, as this was on Long Island, he’d solicit stories from the many students who were also Jewish and had parents/grandparents/relatives who were incarcerated or murdered. And on one occasion, Mr. Shapiro was very compassionate: the boys were in gym class and Benjie, one of the few black kids under his charge, forgot the combination to his locker and was quietly crying as he fiddled with it, naked after taking a shower. Someone had the presence of mind to call Mr. Shapiro and he soon appeared, chastised the fools who were giving Benjie the business, and restored order.

Turning to his twisted side, Mr. Shapiro was also an armchair shrink. One time he suspended a discussion about John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and embarked upon a ghoulish exercise called “Good and Welfare.” The object was for students to open up and discuss what they liked or disliked about their peers. Needless to say, those who weren’t exactly circumspect unloaded their grievances and friendships were ruptured. Ironically, Mr. Shapiro was the biggest loser of the day, when, after a blunt (and not too bright) girl asked him why his dandruff was so acute, he abruptly ended the ill-conceived “game,” and gave his charges the silent treatment for the rest of the week.

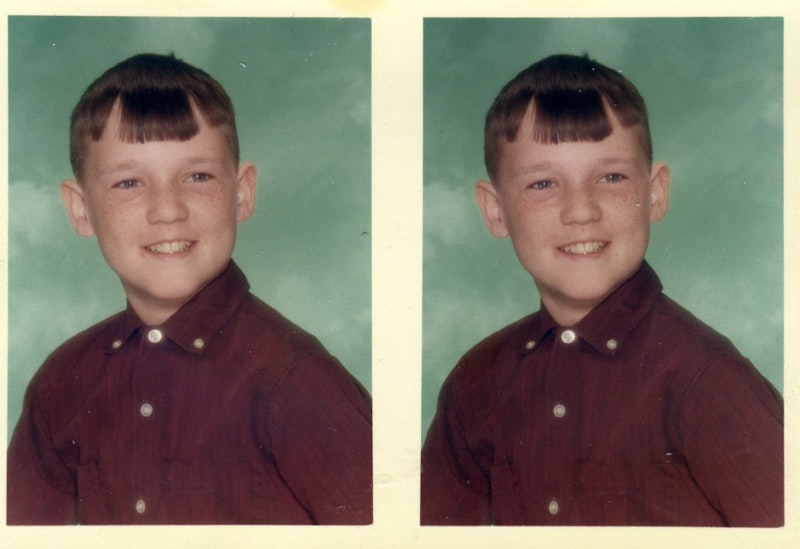

Personally, I got along fine with Mr. Shapiro, and got a kick out of his many idiosyncrasies. It helped that I received good grades and that he knew the family, since one of my brothers was in his class five years earlier. But in the spring of ’67, I was the victim of his cruelty, which no one was spared from (the unflattering picture of me above is from sixth grade). The class was set to stage West Side Story for general assembly, and Mr. Shapiro decided I was perfect to sing—sing!—“Maria” and “Tonight,” pairing me with a sweet girl named Kate Baum. This seemed odd (and horribly embarrassing) since I’ve always had an awful voice and wasn’t keen to demonstrate that fact in front of my friends, let alone the whole school.

I begged off, but the practical joker teacher, doing a Don Rickles, persisted, enlisting the rest of the kids, who were only too happy to egg him on. “Yeah, Rusty, we all want you for the part,” was the sniggering refrain. I refused, the role went to Bruce Humm, a terrific guy, and Mr. Shapiro made fun of me for two straight weeks. I’m sure he forgot about the incident shortly after.

As it happened, I ran into him a few years later at the local A&P, and he was garrulous, full of cheer and we chatted for 10 minutes or so about current events. It was a lot of fun, and though the “Maria” fiasco was in the back of my mind, it didn’t seem so important. Bernie Sanders’ qualified support of Fidel, I suppose, led me to this short reverie of an unusual man from my childhood, a tormented person who probably would’ve been happier had he stuck with the bongos and poetry readings rather than acquiescing to the safety of a career as a grade school teacher.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955