The high school students enter the room and begin the process of turning off electronic devices as they look over the handouts on their desks. I’m giving my second of three presentations on the civil rights movement.

An African-American boy gives another black boy a fake forearm shiver and calls him “nigger.” I cringe at the sound of the vilest word in the English language, but say nothing. A white visiting scholar, I assume, is expected to stay on task. To understand events of the 1960s, I enumerate a list of what it was like when that decade began. Thirty-cents-a-gallon gasoline. Three channels on TV. A week’s worth of cafeteria lunches for $1.25. No gizmos brought to school fancier than a yo-yo.

Outside the window of the Indianapolis-area high school, two uniformed officers stand next to patrol cars. They wear bulletproof vests. Didn’t have that back then, either. I tell the students that my home state of Virginia didn’t desegregate schools until the fall of 1965, when I was in high school. Prior to that, black kids were bused to a school across the street from the Morocco Hotel and its “For Colored Guests” sign in flickering neon.

In my hometown, people of color lived on A St. by the railroad tracks or on Baltimore St. adjacent to the black cemetery. There was no African-American upper or middle class. No factory foremen. No service reps. No delivery truck drivers.

On my first visit to the high school, I'd told the kids about last year’s opening of “Jubilee in the Rear View Mirror,” my two-act play set in 1964 at the height of the civil rights movement. To reflect the segregation of the play’s period, the Evansville audience was divided into separate White and Colored sections. Patrons were assigned to one or the other randomly, not by race. I had interviewed around 50 men and women who went South during the 1960s to desegregate schools and businesses and sign up black voters. (I was told that a common question asked by voting registrars to folks of color was, “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?”) What I learned became background for the play.

The students watched two DVDs we created for the play’s educational pre-show—oral histories of African-Americans in Evansville and Greenwood, MS, who talk about living under segregation until the movement took root. For a long time, this was all the backstory I shared with classes of kids regarding my interest in the civil rights movement. Then one day, a young lady raised her hand. “There’s more to it, isn’t there?” she said. “Yes,” I replied. “So, give already,” she said. “I’m too ashamed,” I replied. A totally inadequate response, I recognized. So now I tell it all when I visit a school.

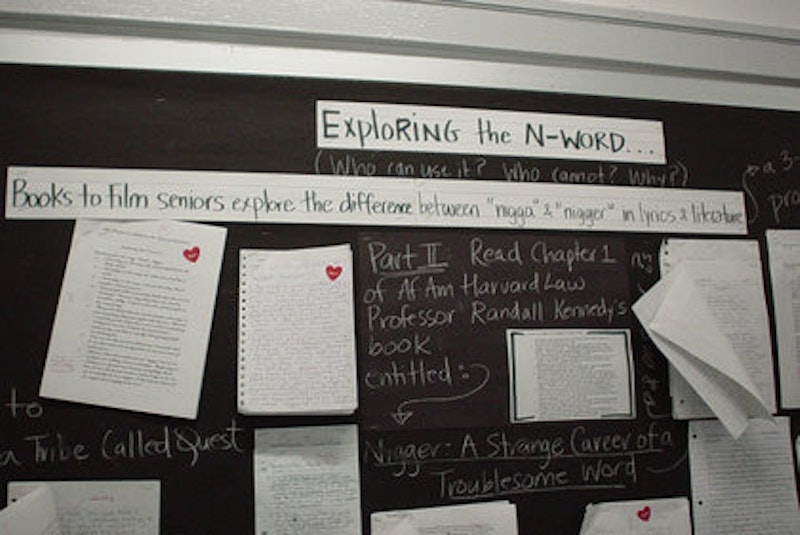

During my first visit to the Indianapolis high school, the teacher had encouraged her students to write down questions for me. Several asked how I feel about the word “nigger.” I was glad. Now the visiting scholar can be on task. The slur has been in the news lately. Its usage is at the core of the bullying imbroglio involving the NFL’s Miami Dolphins. Professional basketball player Matt Barnes recently typed the racial epithet on his Twitter account before deleting it.

“It’s like saying ‘Bro.’ That’s just how we address people now,” Barnes explained. I tell the students “nigger” has long been used by white racists to reinforce the stereotype that persons of color are lazy and stupid. The film 12 Years A Slave contains scene after scene of brutish slavemasters unleashing the epithet on cowering African-American plantation workers who have no choice but to take it. I tell the students they have the civil rights movement to thank for blacks having the right to a quality education, equal opportunities to secure housing and make a buck.

One girl shrugs her shoulders and says her mother greets her every morning with “How’s my little N-word doing today?” Another black girl tells me she has changed her mind about the N-word. “It’s wrong to speak it. I’m not going to do that anymore.” I commend her for having the gumption to articulate a point of view that some of her friends might not share. Later in the day, I see the same girl in the hall. In loud fashion, she drops the N-word. The boy next to her laughs. “It’s like saying ‘Bro.’ That’s just how we address people now.”

—Garret Mathews is the retired metro columnist for the Evansville, IN Courier & Press. A book of columns can be accessed at NewspaperWriter. His email address is garretmath@gmail.com