The last time I saw the Rolling Stones live was at Shea Stadium in October of 1989: one of my brothers had bought a mess of tickets and after an early dinner in Manhattan’s Chinatown we settled into pretty good seats and watched the spectacle unfold. The Stones were dreadful, as Mick Jagger pranced around the stage singing old hits like “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” with all the conviction of a bureaucrat shuffling papers until the five o’clock whistle blew. Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood, cigarettes dangling from their lips, attempted to look like menacing bad boys as they swapped guitar licks, and Charlie Watts could’ve been reading a book throughout the show for all the energy he displayed. Nonetheless, it was fun, as I caught up with my nieces, drank some beers and enjoyed an unseasonably warm night. Unlike most concerts I’d attended, the music was strictly secondary, sort of like a tape playing at a party that’s mostly drowned out by conversation. Occasionally, I’d peer at the stage and watch Mick go through the motions, but it was too depressing to pay serious attention.

I thought about this after reading John Jurgensen’s Wall Street Journal article, “When to Leave the Stage,” last Friday, an evergreen Boomer-oriented essay that posed the question of why rock ‘n’ roll icons from the 1960s, in particular, and later popular bands as well, continue to tour and release albums even though their creativity has long been exhausted. The meat of Jurgensen’s exercise is the second paragraph: “For people of influence in any walk of life, from corporate leaders to sports stars, the question of when to leave the stage is a crucial one. Do you go out at the top of your game, giving up any shot of further glory? Or do you dig in until the end, at the risk of tarnishing a distinguished career?”

But this is a tease, for Jurgensen spends nearly the entirety of the article on pop stars, with more than half the ink devoted to 69-year-old Bob Dylan, and neglects those other titans in “all walks of life.” I’ve no idea of the internal politics at the Journal today, but the author might’ve included at least a parenthetical reference to the proprietor of his newspaper, the 79-year-old Rupert Murdoch. The media tycoon is still functioning at a high level, unlike say, Sen. John McCain (74), who, unable to sacrifice the perks and notoriety of political power, embarrasses himself on a regular basis, most recently with his undignified reelection campaign in Arizona when it was expedient to renounce his previous belief in humane immigration reform. Obviously, you could say the same about Vice President Joe Biden, who’s veering into Nelson Rockefeller territory with alarming speed, and I suspect it won’t be long before he (an inveterate copycat) gives an opponent the finger, just as Rocky did in ’76, not long before died.

And the less said about Jimmy Carter the better. Same with Donald Trump, Warren Buffett, Paul McCartney, Newt Gingrich, David Gergen, Noam Chomsky, Ralph Nader, Alan Greenspan, Barbara Walters, as well as any Kennedy.

This is a rhetorical exercise, of course, a reaction to Jurgensen’s fixation on rock stars; in reality, when a person decides to hang up the spikes (Tim Wakefield?) is his or her own business.

But I’m playing along. When was the last time Robert DeNiro starred in a film (even though at 67 he churns out flick after lousy flick) that even approached one of the at least half-dozen classics that influenced an entire generation of actors? Wag the Dog was terrific, and Dustin Hoffman was every bit DeNiro’s equal in the hilarious film, but that came out 13 years ago. Consider it DeNiro’s equivalent of the Stones’ last-gasp “Shattered” or “Beast of Burden” from ’78.

Who’d have the balls to tell Meryl Streep, 61, to stop starring in fluffy movies? She’s trying to set a record for Oscar nominations and statues, and that’s her choice.

David Broder, the longtime—as in, since 1918—Washington Post reporter/columnist was dubbed “The Dean” by his colleagues years ago, but today he rarely writes anything that, if even read, makes sense of today’s vituperative political wars. Broder must realize that he’s the object of mockery not only among (barely) younger colleagues but also cruel bloggers. Maybe, going by Jurgensen’s description of Dylan’s “scatting Cookie Monster” voice as he continues to play over 100 concerts a year, any political writer who covered Barry Goldwater’s defiant acceptance speech at the GOP Convention in San Francisco more than 46 years ago, ought to retire and play with the great-grandchildren.

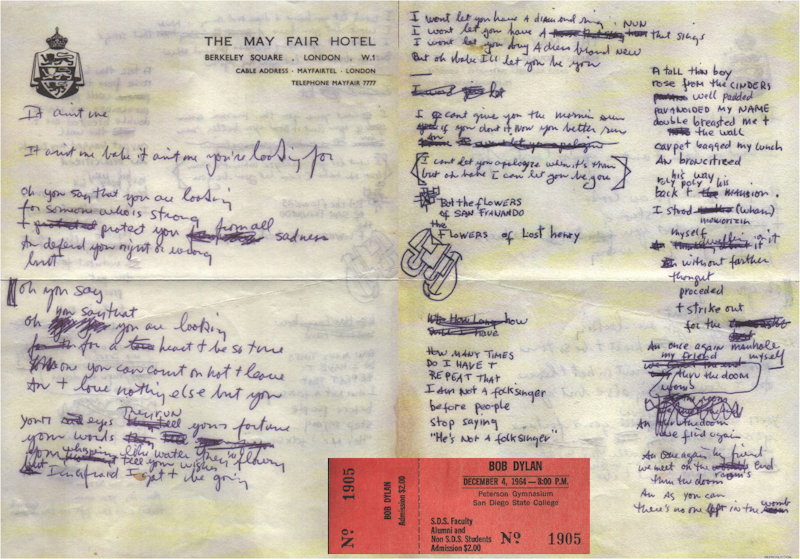

I clearly remember the debate among friends, and in the nascent rock ‘n’ roll press (Rolling Stone, Creem, Crawdaddy and the underground papers), about whether it would’ve been preferable had Dylan died—just like James Dean!—in his ’66 motorcycle crash. He would’ve gone out on top, all right, and this was a-okay with fans who just couldn’t bear 1969’s simple Nashville Skyline (and man, they had no idea of what was coming down Highway 61 in the 80s and beyond), but it always seemed pretty stupid to me. One, we’re talking about a person’s life here, and two, Dylan never believed he owed anything to his devotees.

And really, it’s not very hard to understand why accomplished individuals, even if their most notable achievements are long in the past, don’t feel like “going out on top.” There’s too much money to be made. Is that so hard to understand?

In Dylan’s case, it’s not just about the cash, but also continuing to practice his craft, which is why he plays at obscure venues and consistently (unlike the Stones) re-jiggers his 40-year-old songs. Just the other day, my older son, 18, who was blown away six years ago upon first hearing “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” and “I Want You,” suggested that we go one of Dylan’s concerts when he shows up at a bowling alley or flea market in Maryland. He wants to see Dylan up close, before the singer/songwriter croaks. I’m mildly curious myself, since I haven’t been to a Dylan show since ’78, when he was decked out in a Neil Diamond/Barry Manilow costume and performed such a strange rendition of “Tangled Up in Blue,” that it was far less compelling than a rabbi’s ramblings at a bar mitzvah.

It’s true that individuals who court the spotlight—whether in entertainment, sports finance, politics, media or even academia—are held to a higher standard about retiring when their skills are on the wane. And that’s a bargain they willingly made. Nevertheless, at the most basic level these people are just doing what millions upon millions of non-household names are: working until they no longer feel like it. Besides, regardless of what critics or fans think of them today, aging icons like Dylan and the Stones will be remembered more for, say, “Tombstone Blues” and “Gimme Shelter,” respectively, than their refusal to die young and stay pretty.