Rap and R&B have circled each other warily. Over time, the two forms have started to steal each other’s moves. While serious fans of either genre often despair, fearing the dilution of core values, they should actually be rejoicing: through constant interaction and mutual cannibalization, they exist in a constant state of reevaluation—and, consequently, innovation.

One of the important dividing lines between rap and R&B has traditionally been vocal delivery. Rappers rap; singers sing. But there is also a storied history of rappers singing. In the early 1990s, the gangster rap pioneered and codified by Dr. Dre’s The Chronic made room for mellifluous rapping—from the likes of Snoop Dogg—and luxurious sung hooks, though there was a clear divide: rapper as main event, singer as sidekick who keeps everything laid back. On their 1995 debut, Cleveland’s Bone Thugs ‘n’ Harmony rapped in a singing style, but it was knotty rather than smooth, with tightly-packed bursts of syllables poking through the speak-sing. At the peak of his powers, Lil’ Wayne did whatever he wanted with his voice, though he is usually described as a croaker, not a crooner.

On R&B’s side, 70s artists like Isaac Hayes, James Brown, and Gil Scott-Heron often included spoken-word sections in their albums—Hayes, for example, put several “Ike’s Raps” on his record Black Moses. R. Kelly is happy to speak, sing, or both, aslong as he is flirting, emoting, or both. P.M. Dawn started out in the 90s mixing rapping and singing, before mostly leaving hip-hop behind, and Lauryn Hill did double duty for the Fugees and her solo album. TLC occasionally slipped into rap.

Since Kanye West’s 2008 album 808s & Heartbreaks, on which he abandoned his detailed and wildly successful soul-rap to sing over spare synthesizer productions, the nature of the wall between rapping and singing has changed. It used to be a real, if porous, boundary, with a few people brave enough to poke around a little on the other side before returning to their comfort zone. After 808s, it started to seem artificial, or old fashioned. (Though it still tries to assert itself—think of the Nicki Minaj incident from 2012, when a DJ referred to the Nicki Minaj track “Starships” as “bullshit” not “real hip-hop shit,” partially because it involved singing.)

What’s interesting about post-808s rappers such as Drake and Ty$, who now exist permanently in the middle ground between rapping and singing, is that they are aware they’re onto something. Their albums have become increasingly ambitious, as if innovation in one area is infectious, inspiring these artists to experiment across the board.

Drake, the highest profile exemplar of this trend, sang a lot more on his second major-label full-length, Take Care, than on his first, Thank Me Later. But that wasn’t the only difference—Take Care pushed almost 20 minutes longer than Thank Me Later, and included a couple of long songs with mid-track segues or interludes, which have been used—probably overused—by singers (including Justin Timberlake and Janelle Monae) to signal the depth of their artistry. Drake also collaborated with or sampled hip young outsider musicians like Jamie XX, the Weeknd, and Jai Paul.

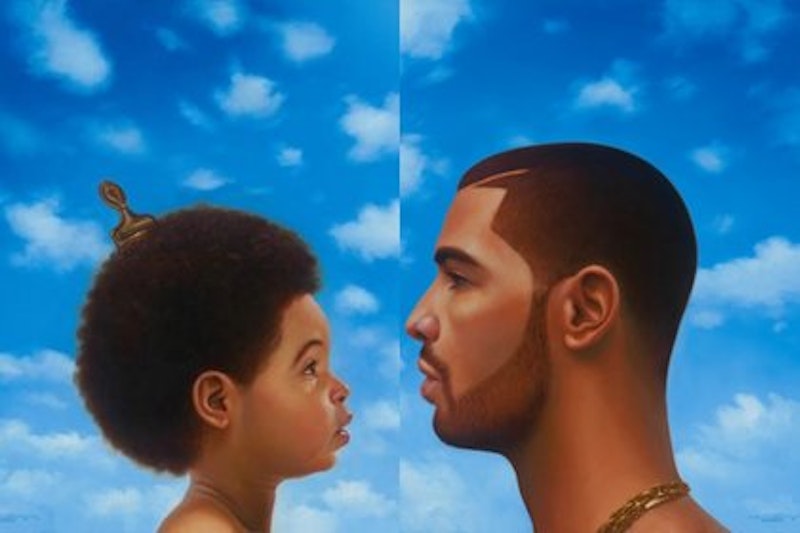

On his new album, Nothing Was The Same, Drake is at his most riveting when moving between rapping and singing. (This is not to imply that when he just sings or just raps, he lacks charisma: “Hold On I’m Going Home,” from the new album, can stand with any of this year’s abundance of ‘80s-influenced R&B productions; “Too Much,” which features fierce rapping over a squeaky, hard-headed beat, bristles with heft and economy.) In “Furthest Thing,” Drake lists places he’s “somewhere between,” and though he doesn’t mention “rapper” and “singer,” he does include “psychotic and iconic,” which someone will surely turn into a lucrative bumper sticker.

Drake’s songs have become increasingly hard to categorize. As a basic beat begins on “Furthest Thing,” his speaking morphs into singing almost accidentally, and then morphs again—soon he’s chanting a mantra, “I still be drinkin’ on the low, mobbin’ on the low/… the furthest thing from perfect like everyone I know.” The second verse starts with singing, then returns to rap, and the song changes too—now it sounds like it’s a hit from the early 2000s, built around piano and sped-up soul-vocals. Drake delivers 16 bars, and things end; it’s a disorienting series of dodges and discards, maybe the trickiest track of his career.

He makes similar moves on “Wu-Tang Forever” and “Connect.” In “Connect” he reverses the order and raps his way into singing: “swanging, eyes closed just swanging/… don’t assume ‘cause I don’t respect assumptions babe.” Most rappers would emphasize the drawled-out cool of “swanging” and articulate the danger inherent in making assumptions. Most singers raise their energy for a chorus, belting it out or adding some vocal embellishments. But Drake sings low and even, stealthily landing an under-stated expression of power.

The west-coaster Ty Dolla Sign is also sing-rapping, and his work has become more and more ambitious. Sure, he remains single-mindedly priapic and firmly grounded in the minimalist approach of the ratchet scene that he’s a part of. But Beach House 2 is filled with self-conscious artistry and unusual moves. Ty Dolla rarely used to push a song past four minutes; now there are slow, almost beat-less stews, and he’s got his own mid-song segues to bring to the table. He displays a new willingness to step back from the streamlined pulse, ready to revel in the stark restraint of the music.

In an interview with The Fader, Ty Dolla noted that once he had success with an early track, “Toot It And Boot It,” which he put together in “five minutes,” “[t]hat let me know that I should do more party shit. I just had to dumb everything down.” But for the most part, his productions on Beach House 2 are not songs you would party to. What he really likes is low and slow, a three-minute track extended as far as it can go without losing all its shape.

Though they don’t sound alike, Ty Dolla’s music is made of the same ingredients as Drake’s: a palette of synthesizers, a few overdubbed backing vocals, streams of thin drum sounds. (Ty usually has finger snaps in his beats, a classic ratchet move that Drake doesn’t care for.) Every line is sing-song rapped.

Like many ratchet artists, Ty Dolla often works around simple repeating synthesizer motifs—the flagship ratchet song, Tyga’s “Rack City,” became ubiquitous a few years ago on little more than a bass lick. There is some of that here, as in “Paranoid,” which was produced by DJ Mustard, who was also behind “Rack City.”

But the songs that Ty produced himself are less interested in momentum, more in stretching sound out over space. “Float”flows over an airy, cooed sample not too far from the Jai Paul sample used by Drake on “Dreams Money Can Buy.” “1st Night” includes faded doo-wop call-and-response and some singing over nothing except steadily fluctuating streams of percussion. At one point, there are intrusions of what could be a guitar or a guy singing through a talk box; later, Ty feels confident enough to unleash a jarring high note. A string instrument pops up in the middle as the track switches gears. The second half may be emptier than the first, with the beat occasionally dropping out at the same moment that a second vocal line enters.

As Ty told The Fader, “I’m doing more hip-hop shit than hip-hop dudes, I’m just singing on it.” You could say a similar thing about Drake—doing more R&B than the R&B dudes, just rapping on it. Rap eats R&B, and vice versa. The boundaries shift, and both genres get better. These artists may be, as Drake suggests, “the furthest thing from perfect.”