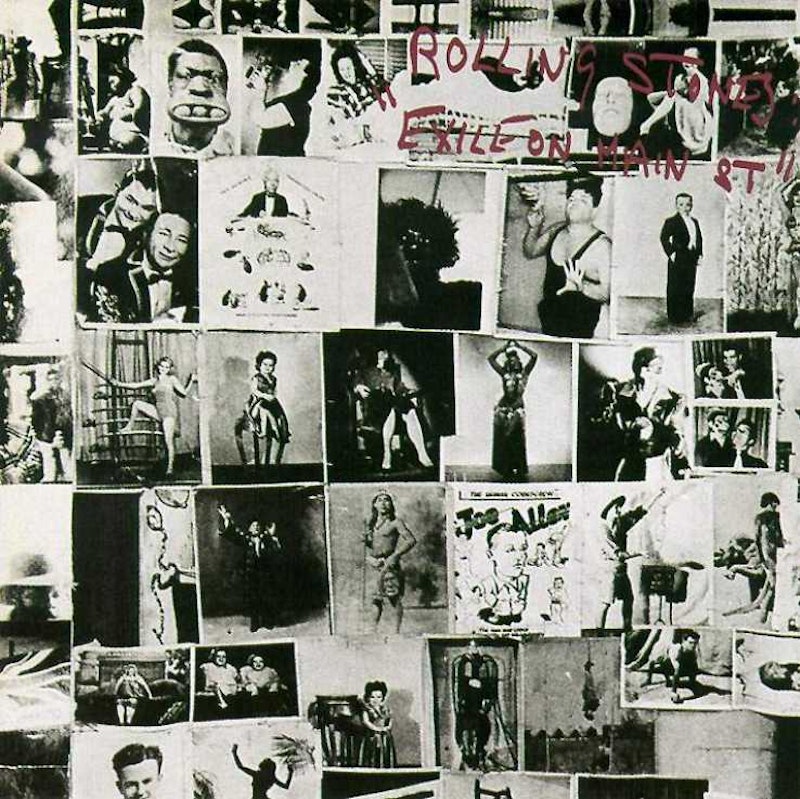

A couple of days before the release of the spiffed-up Exile on Main St., the last superlative album the Rolling Stones made before succumbing to age, boredom, vices and personal squabbles—more generous fans point to 1978’s Some Girls, a spirited comeback for the group, but aside from “Shattered” and “Beast of Burden” I was never sold—I read Ben Ratliff’s review in The New York Times and it nearly gave me hives. Ratliff’s a noted critic and author, but his take on Exile was an odd one, and left me wondering where this guy was in 1972 when the double-LP caused a glorious sensation. As it turns out, Ratliff was born in 1968, and so when he writes, in expressing his lukewarm feelings about Exile, “That era of Stones music, fantastic. [Exile], not so much,” it explained a lot.

That Ratliff, by happenstance of birth, missed out on what he calls “the creative peak” of the Stones certainly doesn’t disqualify him from writing about the band, but without that disclosure—that he’s critiquing from a historical point of view, not as someone who bought and wore out Stones records when they first came out—it gives this particular essay an unsettling whiff of the counterfeit. For example, months ago I purchased a box set of unreleased recordings and radio show appearances by Hank Williams (Hank Williams Revealed), who died before I was born in 1955. Although I’ve read several books about the influential country/rockabilly/folk legend and first discovered his music after seeing The Last Picture Show in ’71, I’d never be able to write about the man as if I were a contemporary.

Pop music critics, regardless of age, can hold forth on whatever they want, but in the fairly rare instances when classic albums from more than a generation ago are given a new shine by companies trying to make a buck on older fans who are suckers (and that would include myself) for previously unheard demos and studio noodlings, I’d just rather read about them from an author who was alive at the time of the original release. This isn’t mere Boomer hubris, for by the same token, my kids would rightfully scoff at a sexagenarian’s long take on a new Interpol record.

I don’t know if Ratliff was even aware of this disconnect upon taking on the re-mastered Exile, but even though his piece has a lot of information and background on the famous record, including quotes from a conversation he had with Mick Jagger, knowing that he never heard, say, “Paint it Black” on the radio when it came out in ’66, makes me suspicious of his gut-level feelings about the Stones.

His first sentence bears this out (particularly after I bought the “new” Exile and re-read his piece): “A lesser-known version of the Rolling Stones’ “Loving Cup,” found on the bonus disc of the new reissue of the band’s 1972 album, “Exile on Main St.,” seems to me the best thing the Stones ever did.”

Say what? Stones fans banter back and forth, even to this day, about the group’s greatest records—Ratliff prefers Let it Bleed and Sticky Fingers; I’d go with Beggar’s Banquet and Between the Buttons—but a discarded version of “Loving Cup” (one of Exile’s lesser songs, in my opinion) is the “best thing the Stones ever did”? Perhaps it was Ratliff’s intention to open his article with a provocative opinion—there’s been so much coverage of this reissue that it’s possible he was straining for an original insight—but give me a minute and I could tick off 25 Stones songs that bury this “new” “Loving Cup.” Such as: “Salt of the Earth,” “Gimme Shelter,” “Connection,” “Jigsaw Puzzle,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Under My Thumb,” “Ride On, Baby,” “Sweet Virginia,” “Monkey Man,” and “Sympathy for the Devil,” just to get the conversation started.

Granted, Ratliff is a regular jazz and pop critic for the Times, but it makes you wonder—even in this diminished era for freelance writers—why the paper’s arts editor didn’t assign this Exile “event” to someone, maybe Greil Marcus or Robert Christgau, who experienced that particular record and the Stones’ “creative peak” as young men. To put it in perspective: Marcus was an early stalwart at Rolling Stone, who famously led off his review of Bob Dylan’s Self Portrait in 1970 with “What is this shit?”; Ratliff, on the other hand, wasn’t even 10 when the Sex Pistols and Clash, among others, flipped rock ‘n’ roll on its head once again, defiantly mocking flabby 60s groups like the Stones.

There are no regrets here for buying the Exile reissue, although the bonus disc is pretty much a bust, with the sole exception of an alternate take of “Soul Survivor” featuring Richards instead of Jagger on vocals, with a completely different set of lyrics. Unlike Dylan, whose “Bootleg” series over the years has often contained revelations, with unreleased gems as well as cleaned-up versions of song that were only available via bootleg, if the extra tracks included in this Exile are any indication, the Stones didn’t leave much behind that was worthy of release. However, it’s an opportunity to re-examine the sprawling, outrageously eclectic menu of material that defines Exile. Jagger was far more involved in this project than Richards, so it makes sense that the vocals, muted on the ’72 release, are ramped up.

Oddly enough, that “improvement” makes Richards’ singing on the terrific “Happy” even brighter and it’s no longer necessary to labor over deciphering the lyrics. Jagger/Richards compositions were never really impressive for the writing, but “Happy’s” an exception with the junkie Richards joyfully belting out these words: “Well I never kept a dollar past sunset / It always burned a hole in my pants” and “Never got a flash out of cocktails / When I got some flesh off the bone.” And “Tumbling Dice,” the radio hit from Exile that washed over the summer of ’72, also has some great lines: “Women think I’m tasty, but they’re always tryin’ to waste me / And make me burn the candle right down / But baby, baby, I don’t need no jewels in my crown / ’Cause all you women is low down gamblers / Cheatin’ like I don’t know how / But baby, baby, there’s fever in the funk house now.”

And it’s a pleasure to listen again, over and over, to a couple of the Stones’ most underrated songs: “Sweet Black Angel” and “Torn and Frayed.”

It’s quaint now, I guess, that the Stones’ ’72 tour, while raucous, exhilarating and security-heavy, concluded at Madison Square Garden that July, instead of Shea Stadium, where they’ve played in recent decades as a nostalgia act. The Stones are given credit for popularizing the Tequila Sunrise, their breakfast beverage of choice that summer; all of a sudden Jose Cuervo had an uptick in sales. I was fortunate enough to see one of three Garden shows in ‘72—tickets were obtained by lottery, and my friend Dave Cicale was a winner and invited me along—and had Ben Ratliff been in attendance I’m betting his view on Exile on Main St. would be different. (It’s a measure of how the industry has changed so dramatically that when I told my nephew I had “great seats” for the concert, his face screwed up, trying to figure out why there would be seats at a performance.) As I recall, Jagger was especially creepy and haunting during “Midnight Rambler,” and “Rocks Off,” “Bitch” and “All Down the Line” were standouts. And the capper was an encore featuring the opening act Stevie Wonder returning to the stage to sing “Uptight” and “Satisfaction” with Jagger and the Stones.

As a middle-aged fellow, my concert days have passed, although I’ll happily watch my 17-year-old son perform in clubs around in Baltimore. And though Ratliff’s suspect review of Exile doesn’t qualify as a lock ‘em up offense, it nonetheless bugs me no end, for he wasn’t there when it all happened.