The thousands of gallons of ink spilled in the last few days to the contrary, the passing of Michael Jackson has offered the public no new insight into the life of the King of Pop. Musically he had long since faded into insignificance, a fact that was unlikely to be altered by next year's proposed comeback tour. His many rounds of scandals had long since stained the affection of all but his most fervent supporters. Even his addiction to painkillers, which seems likely to have contributed to his death, was a well-documented and freely admitted fact. A week ago initiating a conversation about Jackson at a cocktail party would have gained you nothing but confused looks. What are we, writers for Jay Leno? Why don't you drop a Lewinski Joke, while you're at it?

And then Thursday, and the collapse of the Interwebs, and the eulogies on the 24-hour news stations, and the endless commemorations.

What is interesting about any honest retrospective of the work of Michael Jackson is how little of it holds up. Jackson's legacy is ultimately more about what he did to the industry than his music itself; he created and dominated for a brief time a sort of genre-less pop that was palatable to people of almost any sensibility. His earliest work is astonishing, but like any child act (of which the Jackson 5 are unquestionably history's premier) more interesting as a curiosity than anything else. His first classic LPs as a solo artist, abstractly masterpieces of aural craftsmanship, are a bit of mixed bag—for every “Billie Jean” (irrationally catchy and fairly subversive, for a track by the best-selling artist of all time) there is a “Beat It” (a comment on gang warfare that, shockingly, seemed to do little to slow the tide of urban violence in the years after its release). His later work, the fairly execrable Dangerous and the all but forgotten Invincible, don't bear discussing, even to strengthen my argument. No artist, however brilliant, is capable of maintaining self-imposed standards indefinitely, and certainly we all will have need of generosity in our dotage.

But even putting aside the unquestionably bad work in Jackson's repertoire, there is an unfortunate pattern that runs through even the strongest of the man's work, a sometimes choking sense of illusion and artifice. The romantic songs lack eroticism, and his tracks dealing with social justice are, frankly, quite insipid.

To put it bluntly, Michael Jackson lacked Soul. Nor is this simply a factor of a musical style that eschewed the grit of 70s R&B for a more pop-friendly audience. When Sam Cooke's dulcet tones take over from the string opening on “A Change is Gonna Come,” the listener is left with no doubt of Cooke's rage at the injustice he saw around him, or of his mingled hope and despair. Marvin Gaye's "Sexual Healing" is all synths and soft backing vocals, the furthest thing imaginable from the simulated orgasms of a James Brown track, but it has the power to titillate and arouse just the same. Stylized melodies, complex arrangements—these are not necessarily the enemies of passion. But Jackson's music was more than overly cultivated; it seemed not to stem from the fundamental instincts and urges, which inspire great music. Even before this tendency spiraled out of control, with videos portraying Michel as a mechanized super hero or a ghost, his music was still bloodless and ethereal.

An interesting parallel could be addressed between Jackson's unfortunate self-induced physical inversion and his tendency to strip from popular music what his black predecessors had so effectively introduced into it. But armchair psychology is an unattractive habit, and in truth, Jackson's failures as an artist can be adequately summarized without recourse to mention of his race. Popular music of all kinds comes from the gut, and from the groin; whether it's Elvis' hip shaking or Aretha's scorned matron, Sinatra's wounded crooning or the irascible funkiness of Little Stevie Wonder, they latch onto something sufficiently widespread in the species as to be felt irrespective of other differences.

Perhaps it is not shocking that a man who lived a life as utterly divorced from that of the rest of humanity would have difficulty tapping into the universal experiences that are at the heart of great music. He was raised in the musical equivalent of a Dickensian sweatshop and forced to perform erotic ballads as a pre-pubescent by a tyrannical patriarch and the almost equally loathsome Berry Gordy. Pitched into the very height of stardom by a genius act of self-creation in his early 20s, continuously leached off of by family and friends during and after his relatively brief stay at the top. And followed by a seemingly endless third-act descent into decadence, madness, and worse, irrelevance. No, it is not shocking that Jackson was never capable of mustering the fundamental humanness that is required to produce a truly great work of art, popular or otherwise—but it is unfortunate just the same. Because absent this connection, even Jackson's best music is, at best, overly theatrical, and at worst, stilted and bizarre.

He was a werewolf, a zombie, a cartoon bunny, and a basketball player. But at heart he did not seem quite human, and that is what kept him out of the ranks of the true virtuosos, and likely what killed him as well.

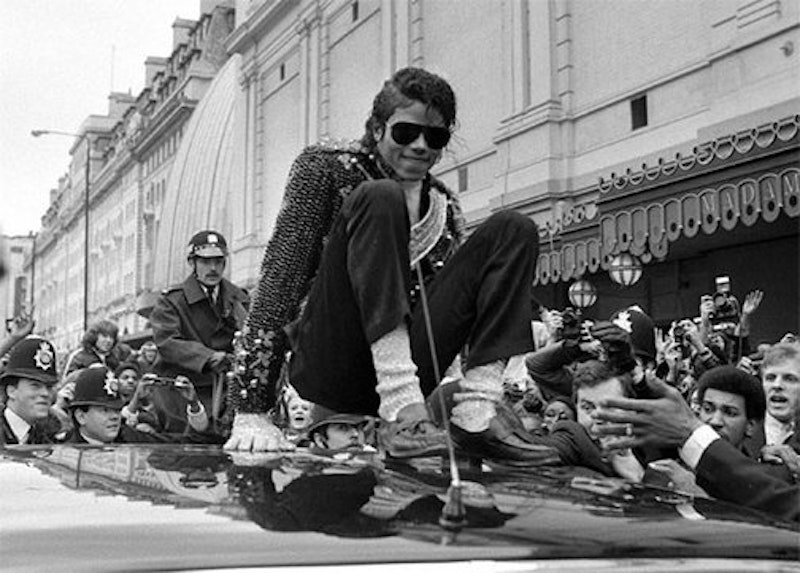

But there was a time. Before the terrible rumors about children, before the megalomaniacal self-obsession, before every hack-comic on the planet discovered MJ jokes were the new airline food. There was a time when the talent of a young Michael Jackson shone as brightly as the sun, the most exceptional prodigy since Mozart. It is sad to think of what might have been.

To that end, a small confection, pre-Motown, pre-everything.