I’m not really sure why someone would want to go back to—let alone revive—the Dustbowl. Horrific dust storms in the 1930s turned hundreds of thousands of people into economic refugees and sent them headfirst into, you know, the Great Depression. This is not the most uplifting of images. But Zachary Lupetin, an occasional Splice Today contributor, named his LA-based band Dustbowl Revival, and that seems to work—and work exceedingly well—however bleak its imagery.

On Dustbowl Revival’s latest record, Holy Ghost Station, Lupetin’s aesthetic borrows liberally from pretty much every mutation of American roots music. Originally from Evanston and its blues-fueled geography, he fronted a loud and brash blues band in Ann Arbor and recorded a record of solo work before graduation. I played some rhythm guitar for Lupetin in that band, The Midnight Special, so I guess this it not what you call an objective review. (I interviewed our former lead guitarist, Gary Prince, and went down the rabbit hole of his work in free jazz, so I guess my subjectivity is an equal-opportunity affair when it comes to my former bandmates.)

Holy Ghost Station is Lupetin’s third record with Dustbowl Revival. Numbering only eight tracks, the record is varied without being scattered. Lupetin recently told me that “the key [is] can you be varied without being schizophrenic. Sometimes being successful is being pigeonholed a bit—so folks know what they are getting. … whatever—the songs just happen as they happen.”

The first two tracks, “That Old Dustbowl” and “Holy Ghost Station,” are straight from Lupetin’s wheelhouse: self-assured, brisk blues and big ol’ stacks of harmonies, as heard on “Straight to the County Line” and “The Ballad of Judas Iscariot” off of Dustbowl’s previous record, The Atomic Mushroom Cloud of Love.

That Old Dustbowl by dustbowlrevival

Dustbowl Revival can sound downright New Orleans some of the time, and with as deep a bench as Lupetin employs, why not? If you got more than half a horn section behind you at all times then you might as well use it. There’s some excellent slide guitar and harmonica in the title track, and the whole album is paced well with tasteful solos and big-band dynamics. “Lowdown Blues” is a romper of a tune, tuba and all, and mandolins and banjos abound. The brains and logistical hive mind of the group, Lupetin cedes the mic for one track, a piece of evidence that this record is a reflection of the range of talent Lupetin employs. Caitlin Boyle provides harmonies throughout, as well as the lovely lead vocals on “What You’re Doing to Me”—a seriously down-home croon of a ballad with sliding horns and mandolins that is somehow able to use the words “camera obscura” without sounding ridiculous.

“Solid Gone” is in the same vein as the opening tracks; there’s something to be said for executing a well-know folk blues template to a high-water mark. Every instrument is in its right place, from a little banjo in the breaks after a verse to some violin in between lyrics and the just-right harmony crescendos.

The record is full of the analog warmth required of an acoustic-based group. “I think it was worth it to work with analog,” Lupetin told me. “Made it very specific. Maybe not as big and radio-friendly as some folks would like but that's not really what this is anyway I guess.”

The prose of John Steinbeck and the photographs of Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans are the cultural-historical baseline for the 30s and 40s, a time when this country went through hell and back only to plunge headlong into World War II. Musically, we have something called the Bakersfield Sound to affix to the period—basically honky-tonk country and bluegrass. It was yet another iteration of the blues—the original cornerstone of American culture—that mostly resulted from tens of thousands of Okies and other Corn Belters migrating to California. This dovetailed nicely with the rise of radio and easily reproducible popular culture, as well as the Great Migration of African Americans to Detroit, Chicago, and other urban centers. This isn’t to say that California was a dearth of country music prior to the influx of folks from the heartland, but, as with any migration in American history, great shifts in people and culture generally kick up yet-more hybrid art forms.

In an interview with PBS, University of Washington Professor James N. Gregory explains further: the Dust Bowl-era exodus “wasn’t the start of a migration; it was a phase of an ongoing, long-time relationship between Texas and Oklahoma and Missouri and Arkansas, and California. People had been coming since the Gold Rush to California, and especially in the teens and 1920s. … A quarter of a million people had come from those very states in the 1920s. So most of the people who headed west in the 1930s had relatives who told them about conditions and could offer some assistance.”

Lupetin and the Dustbowl aren’t consciously saying to themselves, “gee, let’s do this whole Bakersfield Sound thing,” but the spirit of immigration and recombination that made up West Coast blues and bluegrass in the 30s and 40s isn’t all that foreign to what Dustbowl Revival and dozens of other artists are currently doing.

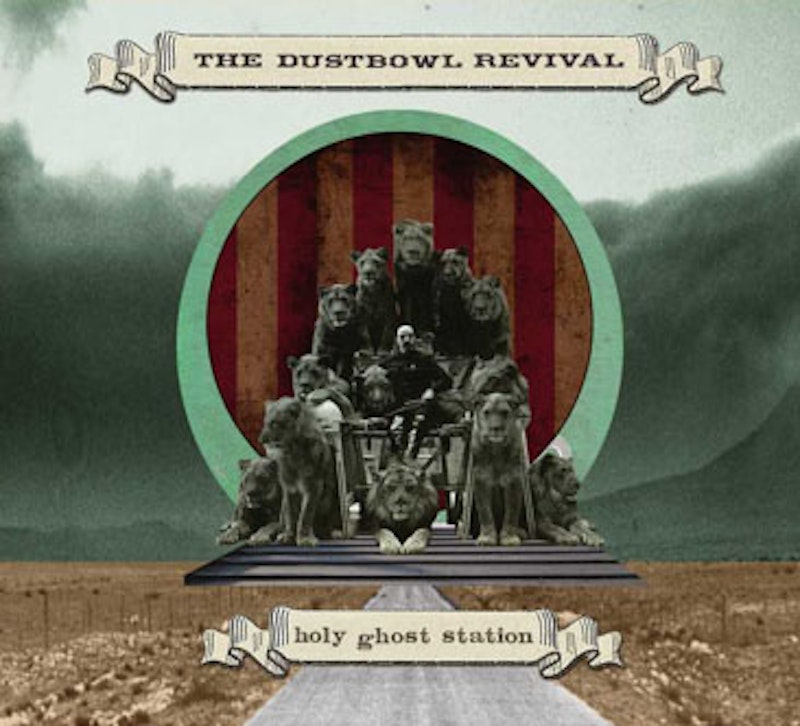

The impenetrably weird and beautiful album is art is courtesy of Sam Strand, who you might remember from this interview. The interior of the case sports a photo of Lupetin surrounded by his bandmates. There’s an accordion, a tuba, a washboard, a stand-up bass and at least one pair of suspenders. No bones about it, this is the makeup of a band intent on barnstorming (they certainly wouldn’t have been out of place on the recent Railroad Revival Tour, which included popular bluegrass/folk groups Old Crow Medicine Show and Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros).

There is a ton of music out there that both harkens back to and builds on blues and roots music. Folk festivals continue to spread like chicken pox from North Carolina to Michigan to California. Dustbowl Revival is in on the ground floor of a lovely new project, Bluegrass LA, which is pretty much just what it sounds like. Here’s their Kickstarter page, worth a few minutes of your time and perhaps worth a few dollars from your wallet.

Holy Ghost Station contains more than its fair share of biblical allusions, not to mention the title. But it borrows as liberally from religion as it does from American roots music. It’s a mature record, a patient record. In eight tracks it traverses across the country (not to mention a little of France on “Le Bataillon” and a little of Mexico on “Western Passage”) and across more than a few decades, and all the while it holds itself together with professional aplomb. Dustbowl Revival is a testament to Lupetin’s expansive palate and the result of a superb cast of musicians. Here’s to more of the same, more of the old, and looking forward to the new.