I've been listening to Frank Sinatra for years. I trace my earliest memories of his songs back to my grandparents’ house in Auburn, N.Y. They enjoyed the music from that era and, although I was too young to have any real musical preferences, his songs sounded fine to me. How can anyone, of any age, not like listening to “Come Fly With Me”?

Sinatra wasn't on the stereo back at home. There, I remember a lot of show tunes. West Side Story and Cabaret come to mind. Music never meant that much to me until I could find my own to like. When that time came, I sure wasn't buying any Sinatra albums. Later on, in college, a close friend from Buffalo whose dad used to play some professional trumpet used to rave about Sinatra, but I resisted. Frank was a cultural artifact of the cocktail generation. As it turned out, my friend was much hipper than I was. He could love both Sinatra and the Velvet Underground and feel no conflict.

It’d be six years after graduation before I'd willingly listen to a Sinatra album, but I got hooked. I bought all his albums I could find, and have regularly listened to them to this day. The voice and the phrasing, combined with his choice of songs and collaborators (e.g. arranger Nelson Riddle) made this nearly inevitable. The single thing that makes Sinatra untouchable as an artist is his ability to convince the listener that he's feeling the emotions he's singing about right in the moment. There's never any doubt. Put him up against a technically brilliant singer like, say Aretha Franklin, and he wins every time on this front. She simply lacks his emotional range and ability to connect with her audience, though her pyrotechnics are superior. Once Sinatra's sung a song, you don't need to hear another cover of it.

While my knowledge of Sinatra’s music is far from encyclopedic, it's solid enough that I was stunned to have just discovered that he produced a lost gem of an album I've never heard of. Compounding the surprise is that fact that it's a concept album named after a town less than a two-hour drive from my grandparents’ place in Auburn where I was first introduced to his music. Watertown, released in 1969, was a commercial flop and is nearly forgotten.

Sinatra owned the 1950s, but Elvis and the Beatles blindsided him. Rock 'n’ roll, a musical style he professed to despise, made him look like a relic. Sinatra hard a hard time even getting his calls returned when that happened. Watertown represents an attempt to remain relevant, with its updated sound incorporating electric guitar, electric bass, keyboards, and drums into the arrangements. The album, mainly composed by Bob Gaudio—who wrote hits for the Four Seasons—is a melancholy song-cycle in which Sinatra adopts the persona of a middle-aged man in a nondescript town trying to make sense of his life after his wife has disappeared. Where she's gone to, or why, remains ambiguous, but he's left to bring up the kids.

Johnny Cash undertaking such a project would be no surprise, but it’s a departure for a jet-setter who’d been on top of the world for so long. Upon closer inspection, however, it's less of a leap. Sinatra never hid his vulnerabilities in his work like he did in his public life with all his bluster. This quality is on full display in his torch song masterpiece, Only the Lonely, but there the listener gets the feeling the artist will emerge from his deep funk. With Watertown, that’s looking far less likely, paralleling the relative place in his career arc Sinatra was at when he recorded these two works. With Watertown, some of the sadness in the voice may be informed by a degree of surrender to the inevitable. He knew he didn't have much new to say.

The eponymous track languidly kicks off the album, setting the stage for the story. “Old Watertown, nothing much happening down on Main 'cept a little rain.” That’s Watertown's reputation. I've driven by it dozens of times on the highway, but have never once been tempted to stop there. Next, on “Goodbye,” the singer juxtaposes the banality of the final breakup—it took place in a coffee shop “with cheesecake and apple pie”—with the emotional devastation it wrought. She won't even tell him why—can't produce one tear. In “For a While,” Sinatra’s conveying the familiar emotions of the brokenhearted when their pain’s momentarily interrupted by mundane everyday events—”some small talk with those I know”—only have it reappear in short order.

The fourth song, “Michael & Peter,” is the album’s highlight. It's written in the form of a letter to his lost wife, as if she was just away on an extended vacation. “I think the house could use some paint,” and “The air still has a country smell.” The final line’s about the children: “You'll never believe how much they're growing.”

In “I Would Be In Love Anyway,” the narrator's saying he'd do it all again, even if he knew how it would end. “Elizabeth” is a lovely ballad, right in Sinatra’s wheelhouse. Few singers could get away with singing “Elizabeth, Elizabeth, Elizabeth” twice in a short song and make it sound great. “What a Funny Girl” is a fond reminiscence of Elizabeth's quirks. The suggestion is that they may have been childhood sweethearts: “We'd spend each night with company. Just you the teddy bears the dolls and me.”

“What's Now Is Now” is the first suggestion that a third party’s involved: “Just one mistake is not enough to change my mind. What's now is now and I'll forget what happened then.” He’ll take her back, but we don't know if she ever hears these words—if he's ever been able to express them to her. In fact, we don't even know if she's still alive.

The penultimate song, “She Says,” portends a happy ending. Sinatra lets his voice soar at the very end with, “She says she's comin’ home,” but she's not. Maybe the singer, unable to let it go, just imagined those words. In “The Train,” he's at the station, in giddy anticipation of his Elizabeth’s arrival: “So many changes since you've been away, and there's so many things to say.” The sun disappears and the rain comes as the train approaches. Elizabeth isn't on the train. “The train is slowly moving on, but I can't see you anywhere.”

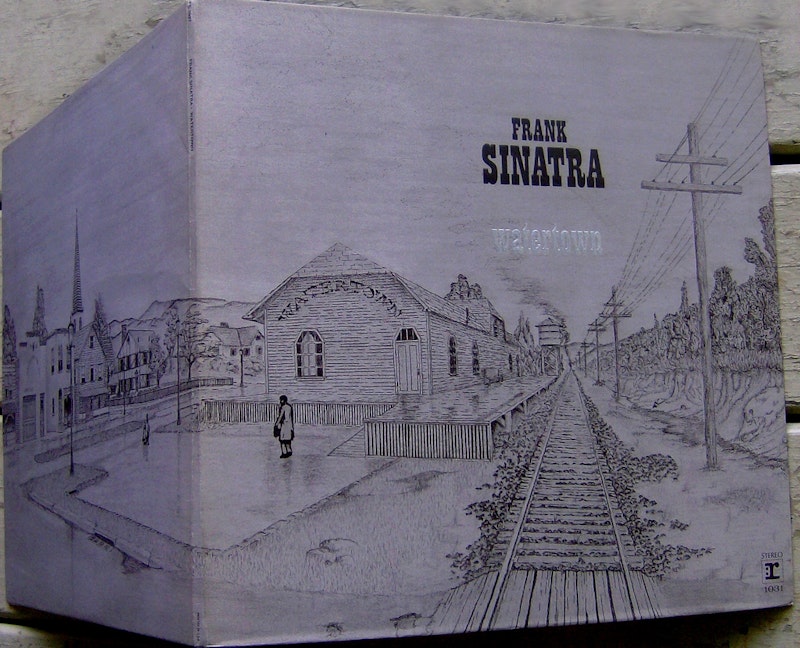

I can't think of an album that feels like more of a piece of literature than Watertown. Sinatra’s vocals add an emotional depth to the words in a way not available to a writer. But the public never took to it. To begin with, the cover art was off-putting. The uninspiring pencil drawing of a Watertown train station is about as inviting as the town itself. Where’s the jaunty drawing of the coolest guy on the planet? The attempt was to look “real,” but it’s more like something hanging in a dusty country antique shop. If you can get past that, you then have to commit to the challenge of piecing together a story of broken love that's far from straightforward. This is a story with an unreliable narrator.

That Sinatra would even attempt to take on this ambitious a work is a measure of his artistry. His peers, if he had any, never stretched themselves like this. He quit the business for some time after Watertown didn't crack the Billboard 100, which had always been automatic for him. Sinatra was at the peak of his powers with Songs For Swingin Lovers, which is so exhilarating. Facing few impediments of any kind, everything fell into place for him and he produced a nearly-perfect album. The pleasures of Watertown are elusive. It lacks the non-stop hooks of songs like “I've Got You Under My Skin” or “You Make Me Feel So Young.” Sinatra was uncertain of his place in the culture by that time. He'd lost his purchase and went for the longshot. Still, the album will live on as a major, unique contribution to American culture, separate from his many hits.