Cancer-riddled, the dying man sings. “I can make you scared,” he promises. “If you want me to. I’m not prepared. But if I have to.”

The last stand of a national legend, scheduled well ahead of time: on August 20, 2016, the Tragically Hip played their last concert with lead singer Gord Downie, in their hometown of Kingston, Ontario. Downie’d been diagnosed with terminal brain cancer late in 2015. Announced early in 2016, the news sent a sizeable percentage of Canada into shock. The country was shocked again by further news—the Hip were determined to launch a last tour with Downie, to fill arenas across the country, and to wrap it up in Kingston.

Rock stars, usually, are either healthy or dead. Glowing golden gods of youth, if they burn out it’s offstage, out of public view. Sometimes they get old, but rarely then do they burn with the stardom of their early days. And if they perform in public they’re typically not under a death sentence. Downie’s case would be different, singing from a liminal state, a shaman half-crossed into the grave, carried on the airwaves of the Canadian Broadcasting Company (on TV, on CBC Radio One, and CBC Radio Two). The Hip would monopolize the national airwaves. Viewing parties were planned across the country.

It’s often said that Americans never understood the Tragically Hip, but that’s a vile and baseless slander. The northern states, the ones who vote like Canadians and play hockey like Canadians, they listen to the Hip like Canadians. Why don’t others? I don’t know. To a Canadian the Hip aren’t difficult to understand. Cerebral, yes, but a cerebral bar band; the best bar band in the world, writing original songs with wit and warmth, fronted by a gifted (and published) poet in Downie. Their early albums were driving rock and meditative ballads, and unlike most rock groups their second full-length, Up to Here, was a marked improvement on their debut. Up to Here was the first of four or five utterly note-perfect albums—not the greatest albums ever made, but discs that couldn’t be made better without turned into something completely different.

It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that the Canadian music industry grew up around the Hip, perhaps the first band to survive as purely Canadian superstars. The nature of Canada means they were bigger in some regions than others, and it’s true that their more abstruse later albums hadn’t had the mass appeal of their earlier work. The band had become more experimental, more abstract. Downie’s lyrics, always a collection of ironic and enigmatic images that sat oddly with the frat-boy popularity of the Hip, became more obscure to match. But the Hip remained the Hip, especially for Canadians about my age, who’d heard something new in their music when they’d emerged almost 30 years ago. They were never the heaviest band in Canada, no Razor, Exciter, or Voivod. But there was a convincing hunger to their rock.

Maybe that explains why they became Canadian icons and maybe it doesn’t, but one way or another there the country was that August night, watching and listening as a dying man performed for us. 6,000 people filled the Rogers K-Rock Centre in Kingston. I listened, on radio, catching some clips on YouTube later. I’d seen them live three times, and now I wanted to hear them, to focus for a last time on their last music. To hear Downie’s voice echoing across the ionosphere, separate from his weakening physical form and image. They started with older songs, but this wasn’t a nostalgia show. New stuff took over. This was a challenging set, a challenging occasion. This was a band that could do anything they wanted and chose to argue that our new stuff is just as good as the old. And made a strong argument.

And Downie sang his heart through his throat. So I could hear over the radio. His voice was raw, angry, and yearning. Aged. And young. Both at once, shamanic paradox. Alive, and captured in a rush to the grave. The set was divided into two, each with its rises and falls. It was when they left after the second set that it really sunk in for me. This would be the last time Downie sung in public, this would be the last Tragically Hip show, and the last song of the last show was coming up.

The first encore was three songs from their second album, Up to Here. “New Orleans Is Sinking.” “Boots And Hearts.” “Blow at High Dough” (Downie miming the pelvic wiggle of “some kinda Elvis thing”). Three songs you’d expect to hear, and then, unexpectedly, just before they leave the stage, a shout-out to Justin Trudeau, who is of course in attendance. “We’re in good hands,” Downie told us. He said Trudeau cares about the folks up north, “the folks we’ve been trained to ignore.”

Even at the time the statement about Trudeau’s care wasn’t as true as one would like. But it was a powerful political moment. Downie’s spent much of the remainder of his time working on Indigenous issues. Last October he released a 10-song concept album, Secret Path, about an Anishinaabe boy in 1966 who escaped a residential school and died trying to return to his home; Jeff LeMire adapted the album into a graphic novel. In December, Downie was honored at the Assembly of First Nations, given an eagle feather and a Lakota name, Wicapi Omani, that means, roughly, “Man who walks among the stars.” Drawing from heaven-only-knows what reserve of energy, Downie's also just announced another solo project, a double album called Introduce Yerself to be released on October 27.

That night in August a year ago the Hip came back for a second encore. They played “Nautical Disaster,” a slow build of a song, emotion building and building and cresting and turning on a dime. A recital of a dream, of a boat crashing and a small lifeboat kicking out the people dragging them down, “and we headed for home,” sung triumphantly “as those fingernails scratching on my hull”—screaming, calling out, searching after the lifeboat roaring home while the water, the water pulls and will not be denied, only for the moment of this one show, two hours and more of a dying man lifting a country out of an awareness of mortality and time.

One might’ve thought that would end it. But it was followed by “Scared.” “I can make you scared/If you want me to,” Downie sang. He stumbled on a line after that, more than a million arts of art whisked out to the woods. But he picked up: “When the Nazis find the whole place dark/They’ll think God’s left the museum for good.” I remember how, listening, I saw every line had new and bleaker meaning: “Tests have shown/That suspicious are hostile/Their lives need not be shortened/Truth be told/They can live a long, long while.” Line after line, meaning one thing when they were written and another there in Kingston that night, there in a different province where I listened to it, there across half a continent to anyone listening. In my memory it is that night and I’m hearing these songs that I have listened to for decades as though they are new.

“If you feel scared, a bit confused/I gotta say/This feels a bit beyond anything I’m used to.” And, finally, inevitably, “I’ve gotta go/It’s been a pleasure doing business with you.”

It’d be too rich a line to end on, too neat and perfect. The Hip’s always spurned the obvious. And so the drums start again and they play “Grace, Too.” Which, here, now, is not a song of endings. But of beginnings, of daring in the face of danger: “Armed with will and determination,/And grace, too!” We know as we hear this that the end is nigh. Will there be more music? One more song between Downie and silence?

Any concert, done well, sequenced right, is dramatic: it draws emotion up to catharsis. Now the appearance of conflict meets the appearance of force. Downie’s words are a focused scream, voice still in control: “Armed with skill and it’s frustration,/And grace, too!” Hypnotic, the song builds and builds and ends. The band waves, each of them kissing Downie, they leave, and we wait. It is a strange agony: will there be more, is it over, can there be anything else, something, some explanation for this ending?

No explanation but more music. “We’re officially in uncharted waters,” says Downie. The band’s never done a third encore. “So let’s see what happens.” What happens is “Locked in the Trunk of a Car.” Raw and powerful, Downie’s voice lashes the arena. So often he has sung elliptical lyrics filled with emotion, latent content, something dreamlike: when you dream of something urgent that you can’t grasp. “It’d be better for me if you don’t understand,” he screams. “Let me out!… Let me out!” It’s nightmarish.

Then “Gift Shop.” A reminder: “The pendulum swings/For a horse like a man.” Downie’s voice soars again—“And after a glimpse/Over the top/The rest of the world/Becomes a gift shop.” Glints of meaning, regret, joy, value, all things once unmeant and that now cannot be not heard or unheard. “We’re gonna give you one more, and then we’re gonna hit the road,” Downie promises, as the song winds down, and gives a series of whoops.

The last Tragically Hip song was “Ahead By a Century” (those listening on CBC radio heard host Rich Terfry heavily hint as much before the last encore, in one of the most stunningly idiotic moments I’ve heard on radio). Acoustic guitar and Downie’s voice evoking a childhood in a summer day. “This is no dress rehearsal/This is our life.” And we had across the country a feverish dream, as his voice scaled up to high notes in the climax. Rain falls in real time. This is our life. But that’s when the hornet stung me, and I had a serious dream.

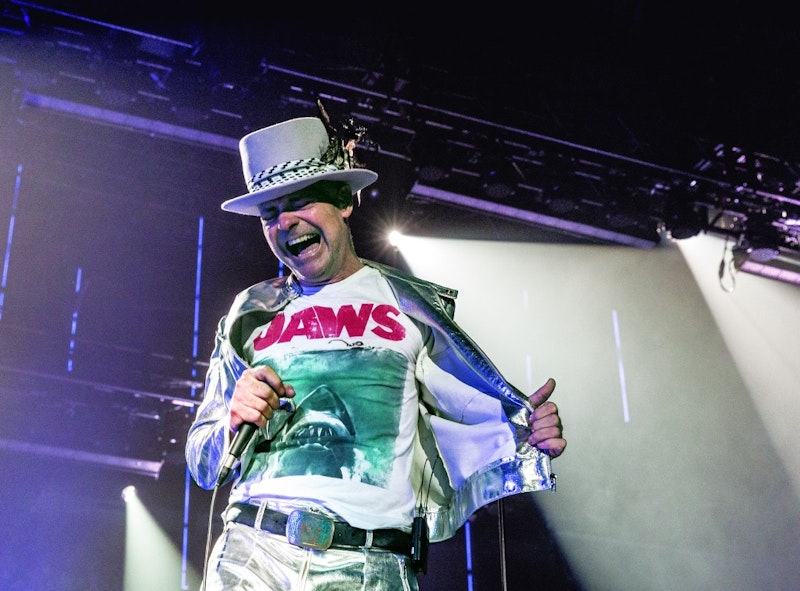

The song ends with a long instrumental coda; Downie doesn’t walk off on a final scream, not on a literal high note. But on the band’s teamwork. And it’s done, the shamanic trip completed. Nothing’s learned that you can point to or iterate like a student in front of a class. But there’s something new-felt, to me, some shivering secret of death not revealed but embodied, incarnated. Music, dance, drama, ritual. Uncharted waters. Symbolic costume: articles across Canada were to be written about the Jaws T-shirt Downie wore, the shark arising through waters to the hapless swimmer.

The altered state of consciousness a concert creates is a kind of mystic trance. You can feel it but can’t say why it’s important, not wholly, only quarry out words from the sense of meaning and out of those words fashion a skein to outline but not capture the essence. In this case not the unalloyed dream of power and youth typical of self-conscious rock ‘n’ roll. This was to do with the inevitability of death, just a little bit. It didn’t leave me wiser, or more knowledgeable, but created that state in which sung words have power. Sometimes the faster it gets the less you need to know. Only it made a sound in my memory, the last goal he ever scored, so regal and decadent here, coffin-cheaters dance on their grave.

Nothing’s dead up there on that stage, nothing’s dead down here. It’s just a little tired.