Is culture becoming more diverse or less diverse?

On the one hand, there're more cultural products available to more people than ever before in history. You can go online and find everything from traditional Thai music set to trashy 80s dance music to John Carpenter's The Thing acted by claymation penguins. Whether sublime, ridiculous, or X-rated, the music and art from everywhere is available everywhere else. Capitalism and the Internet have combined to offer an infinite virtual smorgasbord. Once Harry Smith had to burrow through crates to bring us music from our own rural South; now you can listen to the most outré sounds from clear around the globe with just a click of a search engine.

And yet, is it possible that the very ease of access homogenizes? I love Pamela Bowden's hybridization of Thai luk thung and dance, but it's Westernized in some sense. Culture has always hybridized, of course, but the speed has accelerated exponentially. If the Internet can be a treasure trove, it can also be a wasteland; an infinite expanse where you click from one hollow, predictable meme to another, with everything mashed into everything else to form one giant, bland bolus of quirky irony.

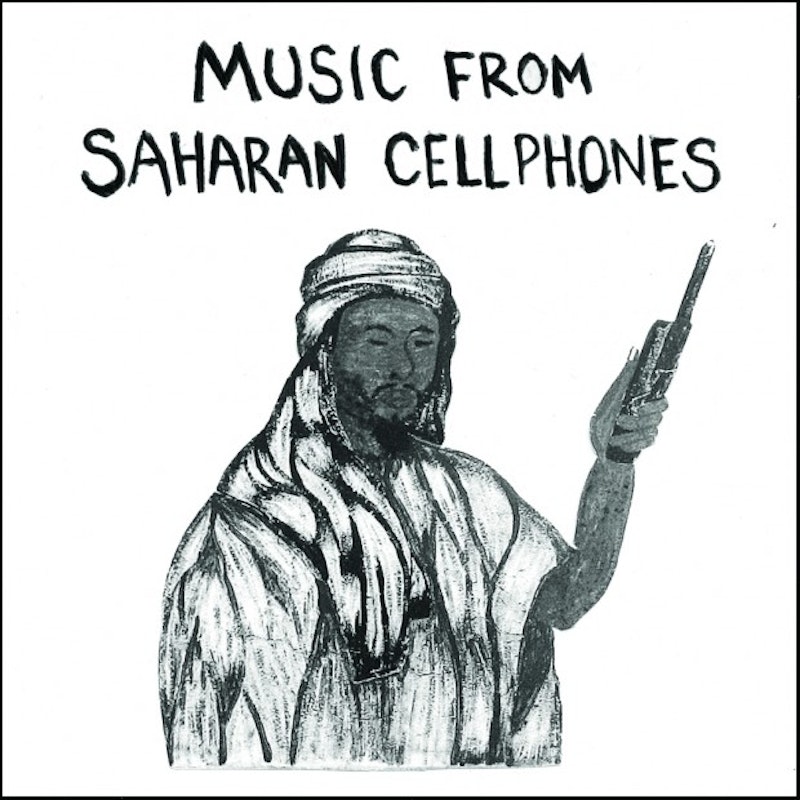

Music From Saharan Cellphones, a recent release on Sahelsounds, doesn't so much answer these questions as underline them. The anthology is just what it says, as collector Christopher Kirkley explains:

One of [cellphones'] most important uses [in the Sahara] is the storage and playback of MP3 collections. Built in speakers blare at all times, during the promenade down dusty streets, while conversing around a boiling pot of tea, or on the delirious and crowded bus journeys, the Sahelian soundscape is filled with an orchestra of tinny digital audio. Should a song catch your interest, it is as simple as asking for a copy. Music is traded through a very literal peer-to-peer transfer, utilizing the built in Bluetooth capabilities to swap songs.

The album includes everything from regional hits—like rapper Yeli Fuzzo's "Abandé" to the aggressively obscure, like Group Amataff's "Tinariwen," a song that was initially distributed to a handful of friends. Digital distribution, in this case, doesn't so much homogenize as it enables. Cellphones and MP3's create an audience, and foster a scene. Kirkley points out that many songs are made using pirated beat making programs, or even recorded on the cellphones themselves.

There are undoubtedly some unique sounds here; my favorite is perhaps Mdou Moctar's "Tahoultine," a Nigerian groove that, thanks to autotune, sounds like it's being performed by a castrated robot. Negib Ould Ngainich's brief "Guetna," an instrumental tune for keyboard and drums, has a stuttering, repetitive percussive shimmer that sounds a little like Steve Reich (who was probably influenced by similar African sources) and a little like bachata, of all things.

But even such singular moments don't change the fact that overall, Music From Saharan Cellphones is not nearly as surprising or abstruse as its title promises. That Group Anmataff track that was distributed to a handful of friends, for example. It's really nice groovy African funk, and I like groovy African funk, but if you've heard Fela, this isn't exactly going to rock your paradigm. Similarly, Papito's "Yereyira" is a worldbeat hip-hop track which is cute, but, again, not especially revelatory. The truth is, you could imagine everything on this album showing up on an NPR broadcast. Except maybe for that Mdou Moctar track—the autotune there really is gloriously annoying.

The autotune, though, is itself a much-loathed technological innovation. If you wanted to, you could decry the way it has insinuated itself into the furthest reaches of the globe, just as I've decried the fact that even the furthest reaches of the globe sound like they're just waiting to be rationalized by a Rough Guide mix CD.

Maybe though, the issue isn't so much whether diversity or novelty persists so much as what exactly we think we're doing when we look to Thailand, or the Sahara, or wherever, for that ever-retreating, ever-elusive diversity. The Sahara and its cellphones aren't there for the benefit of my jaded pallete, after all.

And yet, in some sense, they are; those MP3's have been packaged, appropriated, committed to vinyl, and shipped overseas for my listening pleasure. The truly insidious thing about our cultural landscape is not that it homogenizes, but that it offers up an ever-more distant, and simultaneously ever-more accessible, other—a beautiful, evanescent mirage of difference in the tractless waste of our selves. The hope is that when you phone that number in the desert, the people on the other end will be so utterly ignorant of you, and you of them, that the stain of your identity will be instantly erased. In the end, though, culture is just culture, however distant. There's nobody else out there to grant us absolution.