On September 21, 2004, a United Airlines flight traveling from London to Washington D.C. was diverted to Bangor, Maine. Six federal agents came aboard and took into custody a 57-year-old British man traveling with his 21-year-old daughter. “Are you Yusuf Islam,” the agents demanded. The man confirmed he was. “Do you spell your name Y-O-U-S-U-F?” “It’s Y-U-S-U-F,” the man answered. His daughter was allowed to continue traveling but the man was denied entry to the United States. He was flown back to England the next day. Homeland Security officials explained the man had associations with potential terrorists.

Yusuf Islam was not always treated this way. Thirty years earlier he was one of the biggest pop stars in the world. He played to 40,000-seat arenas and hung out with the likes of Paul McCartney and Bob Dylan. But those days were a lifetime away.

He was born Steven Georgiou in London in 1948. His father was a Greek Cypriot and his mom was Swedish. They owned and lived above a restaurant called Moulin Rouge where he was put to work washing dishes at the age of eight. When he was 15, his father bought him a guitar. He escaped to the Soho rooftops, a quiet refuge he called “the Upper World.” He began writing and playing his own songs influenced by the Beatles, the Kinks and Nina Simone.

By 18, he was performing in London coffee houses and pubs. He changed his name to “Cat” because a girlfriend said he had “cat eyes.” He was signed to a record deal and his 1966 song “I Love My Dog” reached #2 on the British charts. Cat Stevens became a teen idol touring the country with Jimi Hendrix and Engelbert Humperdinck. Hendrix introduced him to psychedelics and Stevens spent the next few years overindulging in drugs and alcohol.

In 1968, Stevens contracted tuberculosis and nearly died. While in the hospital, he began to question his life. He took up meditation and yoga, became a vegetarian and immersed himself in spiritual and religious texts. He covered the mirrors in his hospital room “to get away from the external and to start digging deep” into himself.

After a year of convalescence, Stevens returned to music with a new beard and new sound. His songs embraced a folk-rock style with introspective lyrics about everyday problems and spiritual questions. Stevens signed with A&M Records and released Mona Bone Jakon (1970), Tea for the Tillerman (1971) and Teaser and the Firecat (1972), all gold records. They included the hit songs “Trouble,” “Where Do The Children Play,” “Wild World,” “Moonshadow” and “Peace Train." The 1971 dark comedy Harold And Maude used nine of his songs for the soundtrack introducing his music to a wider audience.

Though he’d become one of the biggest stars in the world, he still lived with his parents. Fans made pilgrimages to the Stevens’ home and were often invited in for tea by his father. Stevens was becoming disillusioned with the music industry. He despised the competition and greed, feeling like a pawn subjected to the whims of managers and record executives. In 1973, he moved to Rio de Janeiro and became a British tax exile. He continued touring, donating his profits to UNESCO.

During a 1976 trip to Los Angeles, Stevens visited the Malibu home of Jerry Moss, co-founder of A&M. He decided to take a swim in the ocean. He was caught in a riptide and taken far from shore. He struggled for several minutes losing all his strength. Certain he was about to drown, he shouted, “God! If you save me I will work for you.” A large wave appeared and carried him back to shore. The near-death experience rekindled his yearning for a spiritual life. “What arose within me was a deep conviction that ultimately there is a higher control over one’s life.”

His brother David gave him a copy of the Qur’an. Stevens took to it immediately. “I couldn’t put down,” he said. “No matter what I tried to say in my songs, they were all part of the Shadow. In the Qur’an I found a Light.”

Stevens identified with the Biblical story of Joseph, a man who was bought and sold in the marketplace. He felt the same way about himself and his place in the world of music. He realized he didn’t want to be Cat Stevens anymore. In 1977, he formally converted to Islam. He took the name “Yusuf,” Arabic for Joseph.

He kept his conversion out of the public eye and gave his final concert as Cat Stevens at Wembley Arena in 1979. At the end of the concert, he told the audience, “We’ve only got one life and you have to do the best with it. You have to find the right path and when you do, you know it.” Cat Stevens walked off stage as Yusuf Islam never intending to perform again.

He sold his guitars and gold records and gave the money to charity. While the Qur’an didn’t prohibit music he felt he had to give it up to become a true Muslim. He later said, “The music business was filled with things like vanity, fornication and drug use. If I was going to make the change, I had to get away from that.”

Yusuf’s life changed completely. He married Fauzia Ali in a religious ceremony and the couple had five children. He dedicated himself to the study of the Qur’an and his new passion became education. He used his music royalties to establish several Muslim schools in England. The curriculum balanced spiritual teaching with a material focus on math, science, and writing. He also founded the Small Kindness charity assisting orphans in Africa and famine victims in the Balkans.

In 1989, he became embroiled in the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. Asked for his opinion by a reporter, Yusuf replied that the “legal Islamic punishment for blasphemy was death.” The next day, newspaper headlines reported: “Cat Says Kill Rushdie.” Yusuf denied supporting the fatwa but the damage was done. American radio stations refused to play Cat Stevens songs. The band 10,000 Maniacs was forced to remove the song “Moonshadow” from their new album. He’d become a pariah.

Yusuf continued his work for charity and education. During the Bosnian conflict, he became involved in relief efforts for Muslim war victims. A survey of British Muslims named him the most highly regarded Muslim figure, more influential than imams and scholars.

In 1994, while vacationing in Dubai with his family, his son brought a guitar into the house. One morning after prayers, Yusuf picked up the guitar on the couch. He hadn’t played in 25 years but still remembered the chords. He started playing his early songs including “The Road To Find Out” which included the lyrics:

I left my happy home to see what I could find out.

I left my folk and friends with the aim to clear my mind out.

The answer lies within, so why not take a look now?

Kick out the devil’s sin, pick up a good book now.

When Yusuf learned that Muslims had introduced the guitar to Europe he changed his mind about the role of music in Islam. Slowly, he resumed his musical career, appearing at a 1997 benefit concert in Sarajevo and releasing a children’s album in 2000. After the September 11 attacks, he appeared on a VH-1 Concert and sang “Peace Train” for the first time in public in more than 20 years.

At the time he was deported from the United States in 2004, he’d been traveling to Nashville to meet Dolly Parton for a new music project. Parton was one of the few celebrities to come to the defense of Yusuf. She told the press, “The government made a mistake. I can’t imagine there’s an evil bone in that man’s body. Those are the people you’re supposed to cherish. You don’t walk on the hearts of angels.”

In 2006, Yusuf released his first new pop album in 28 years. He began touring again and included Cat Stevens songs on his playlist. He’ll be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame later this year.

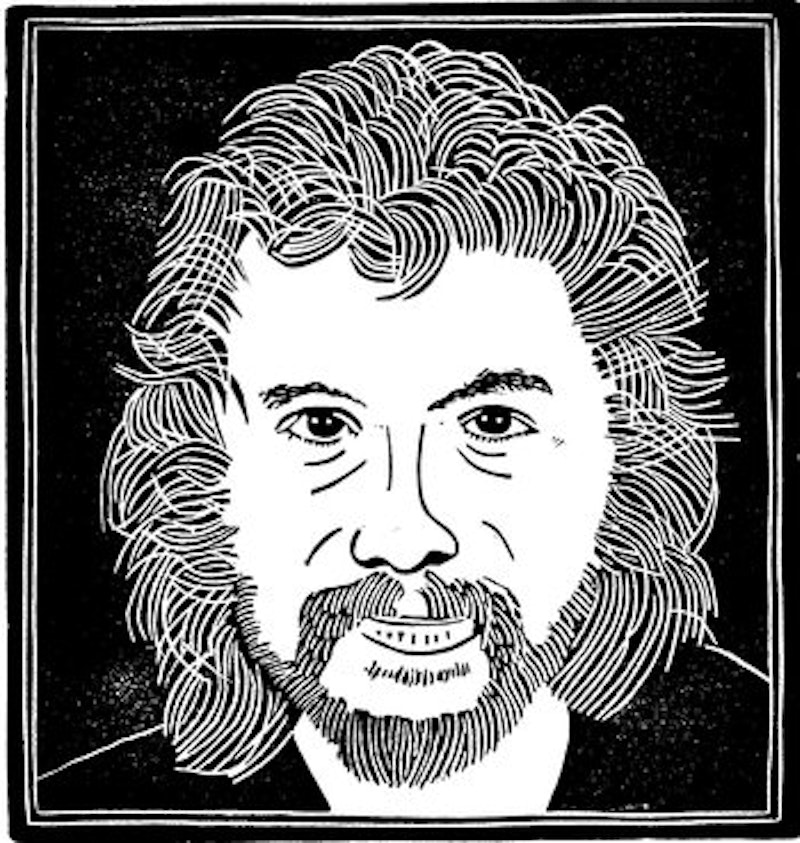

—See more Loren Kantor at: http://woodcuttingfool.blogspot.com/