"A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" (1963), written and performed by Bob Dylan: This lyrical triumph is a seven-minute warning that the apocalypse is nigh. The End of Days is arriving in the form of a "hard rain" because mankind messed up God's pristine world with its wars, inhumanity, and pollution. Dylan portrays an ugly world full of "crooked highways," "sad forests," child soldiers ("guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children") and a baby surrounded by wolves. “It’s all one long funeral song," as Dylan would later put it, but it pulls back from the abyss right when it reaches its edge. The "blue-eyed son" who's just provided a litany of the world's misery turns sanguine when asked what he's going to do about it—he's not giving up. Instead, he's going to get out there "'fore the rain starts a-fallin'" and "tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it."

"When the Man Comes Around" (2002), written and performed by Johnny Cash: "Death smiles to us all. All a man can do is smile back." Those words ring true in the midst of this pandemic, when giving in to fear is an emotion to wrestle with. This song, partially inspired by Revelation 6:1-2 and one of the last songs the country legend wrote, is just Cash strumming an upbeat rhythm on his guitar as he sings and talks the portentous lyrics. He uses his wobbly baritone voice to lend solemnity to this story about the final judgment: "There's a man goin' 'round takin' names/And he decides who to free and who to blame.

The verses are tense, speaking of Armageddon and terror. The chorus is an antidote to the tension, with its celebration of the Second Coming: "Hear the trumpets, hear the pipers. One hundred million angels singin'." Cash manages to find the right balance between hope and fear.

"Wooden Ships" (1969), written by Stephen Stills, David Crosby, and Paul Kantner, performed by Crosby Stills & Nash: This is one of the songs inspired by the threat of nuclear destruction before people understood that the main victim of the Cold War was going to be the Soviet Union. It focuses on the aftermath, when people have escaped the fallout by sailing away to distant shores on wooden ships. It speaks of an encounter between two people on opposing sides of the nuclear divide, suggesting that past differences no longer have meaning now that everyone's just trying to survive: “I can see by your coat, my friend/You're from the other side/There's just one thing I've got to know/Can you tell me please, who won?” Obviously, nobody won, but CS&N bring beauty to the post-apocalyptic struggle with their lovely harmonies and Stephen Stills’ guitar work. Jackson Browne responded to the "Wooden Ships" fantasy scenario with “For Everyman” after hearing the song and wondering what would happen to all the people who stayed behind and tried to put things back together after the holocaust. David Crosby sings, "We are leaving, you don't need us.”

The song also appeared on Jefferson Airplane’s 1969 album Volunteers.

"This World Over" (1984), written by Andy Partridge, performed by XTC: This is a minor-key Cold War song that succeeds in projecting the appropriate mood of doom and gloom associated with the worst-case nuclear scenario that lingered in the back of the collective consciousness during that era. Morrissey once described the tune as, "Anti-war holler, wistful and winsome." It's representative of the tranche of anti-war songs that the British pop music industry produced in the 1980s targeting Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. The narrator (Partridge in his Angry Man persona) is addressing a mother with young children: “Will you tell them about that far off and mythical land/About their leader with the famous face?/Will you tell them that the reason nothing ever grows in the garden anymore/Because he wanted to win the craziest race.”

Reagan's the famous face, but Partridge turned out to be wrong about his brinksmanship destroying the world. In retrospect, the song is overwrought, but it's still an effective distillation of the nuclear-age paranoia of the time. The arrangement starts off stripped down—mostly a mellotron playing over a sampled drum beat. Studio-enhanced instrumentation's added as the song picks up steam. Partridge is such a fine tunesmith that he can make even a song about annihilation catchy. XTC never achieved more than a cult following here in the U.S.

"The End" (1967), written by Jim Morrison, Ray Manzarek Robby Krieger, and John Densmore, performed by The Doors: The Doors get dark and exotic on this one. Morrison kicks off the song singing about the end as “my only friend." What started as a breakup song by the singer eventually evolved into an Oedipal account of a psycho terrorizing his family. The Doors got a chance to develop the song over time when they were the house band at L.A.'s Whisky a Go Go in 1966. Having to play two sets a night, they needed to extend their songs in order not to run out of material. This gave them freedom to experiment, and the end result was a 12-minute version of "The End" recorded live in the studio for their self-titled debut album.

The song has the feel of an Indian raga, with Robby Krieger's meandering, haunting guitar imitating a sitar. The drum beat sounds like a tabla, and Ray Manzarek's mimicking a tambura with his keyboard. While it came out well before the movie, "The End" seems like it was written for Coppola's Apocalypse Now. The song's a cathartic, mesmerizing exploration of the darker elements of Jim Morrison's subconscious.

"The Earth Died Screaming" (1992), written and performed by Tom Waits: Waits' hoarse rasp makes a perfect vehicle for conveying the fear that the apocalypse instills. He envisions a horrifying place, reminiscent of Yeats' "The Second Coming," where there are "crows as big as airplanes" and three-headed lions that shed their skin, which someone will then eat. Waits talks his way through the verses, only singing in the chorus: "And the earth died screaming/While I lay dreaming/Dreaming of you." If you think death metal is as menacing as music gets, check out this one, in which the musician showcases his propensity for offbeat instrumentation. He achieved one effect by having a group of people banging two-by-fours against stones or wood on the ground.

"Five Years" (1972), written and performed by David Bowie: The world will last only another five years, according to Ziggy Stardust, Bowie's bisexual-alien-rock-star alter ego. Ziggy provides an inventory of everyday sights he's noticing now that the coming apocalypse may snuff them out: "I heard telephones, opera house, favorite melodies/I saw boys, toys, electric irons and T.V.'s." The message is that the end of the world will bring out the best and worst in humans: "A girl my age went off her head/Hit some tiny children/If the black hadn't pulled her off/I think she would have killed them." Some are taking the bad news in stride: "Think I saw you in an ice-cream parlor/Drinking milkshakes cold and long/Smiling and waving and looking so fine/Don't think you knew you were in this song."

Bowie's voice transforms from wistful to strident by the time he reaches the emotional crescendo of the chorus, which is repeated over and over at the end: "We've got five years, stuck on my eyes/Five years, what a surprise/We've got five years, my brain hurts a lot/Five years, that's all we've got."

"London Calling" (1979), written by Joe Strummer and Mick Jones, performed by The Clash: This song was written in a minor key, a rare choice for the band. Strummer's primal howling amplifies the paranoia and desperation he details as he sings about the terrors of the coming ice age and a "nuclear error," a reference to the Three Mile Island nuclear meltdown of 1979. London was a bleak city in the late-70s, especially from The Clash's left-wing perspective, and "London Calling" captured the despair in a flamboyant fashion.

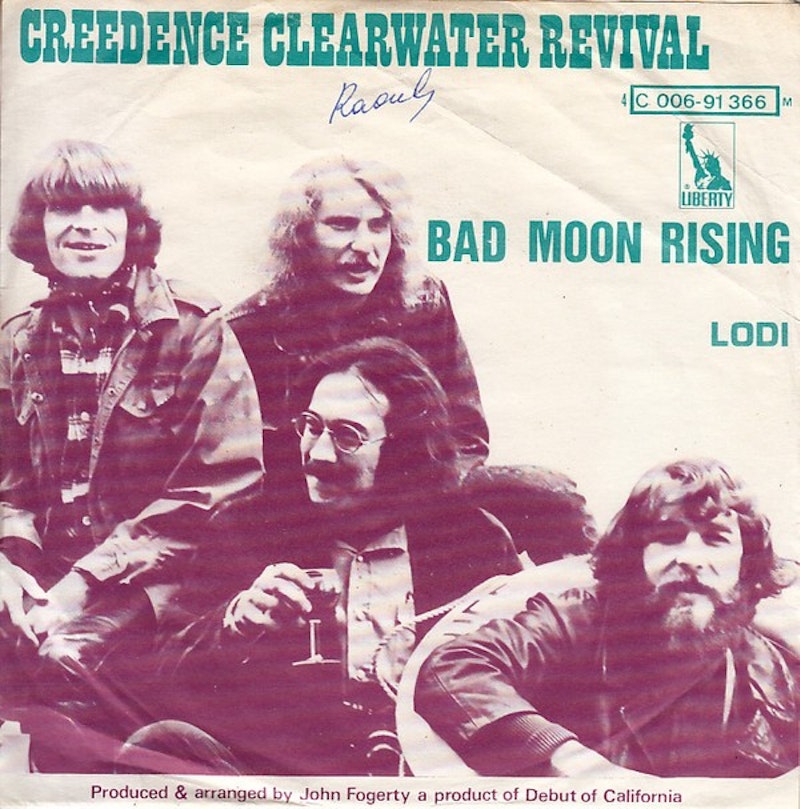

"Bad Moon Rising" (1969), written by John Fogerty, performed by Credence Clearwater Revival: This rockabilly-tinged song, a staple of movie soundtracks, captures the turmoil of the late-1960s. Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated, and Richard Nixon had recently been elected. Fogerty said it "is about the apocalypse that was going to be visited upon us." The single peaked at number two in the U.S. in June, 1969. CCR never had a number one record, but that's mostly a fluke. Henry Mancini's "Love Theme from Romeo and Juliet" was the song that prevented "Bad Moon Rising" from making it to the top of the charts.

Musically, it's a bouncy song, but the lyrics offer a counterpoint with their bleakness: "Don't go 'round tonight/It's bound to take your life/There's a bad moon on the rise."

"I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" (1967), written by Country Joe McDonald, performed by Country Joe and the Fish: No list of doomsday songs would be complete without one that uses humor as a coping method for dealing with impending death―albeit dark humor. Country Joe McDonald, who'd served in the US Navy, wrote it as an indictment of all the powerful people who wanted to see young men shipped off to Vietnam for their own selfish purposes: “Come on Wall Street, don't be slow/Why man, this is war au-go-go/There's plenty good money to be made/by supplying the army with the tools of its trade.”

It's the chorus that made this song a singalong favorite of the 1960s hippie and anti-war crowd: “And it's one, two, three/What are we fighting for?/Don't ask me, I don't give a damn/Next stop is Vietnam/And it's five, six, seven/Open up the pearly gates/Well there ain't no time to wonder why/Whoopee! we're all gonna die.” This is the lyric, addressed to fathers with sons going off to war, that will stay with you: “Send your sons off before it's too late/And you can be the first ones in your block/To have your boy come home in a box.”