The women sing sad songs of lost love and subsequent substance abuse; they sing about poverty, escaping your small town and yearning to return; about their mamas, or being mamas; about their female friends and the hideous vengeance they’ll visit on that cheating man. They sing these songs in a way that invites immediate and intimate connection to their vulnerable human voices. They confess, or they create characters and place them into ballads of love or murder or friendship or fun, over a band strumming acoustic guitars and smacking actual drums. In other words, though it doesn't sound quite like 1990 or 1970 or 1950, it is definitely country music.

The men, on the other hand, are limited thematically to pretty girls and positive booze experiences. It's still called “bro” country, and it runs ever-closer to mainstream pop: the tracks assembled rather than played, dominated by electronic beats, vocal effects, and party themes. Often what signals "country" is just that the artist has a camo baseball cap on, or maybe that there’s a touch of possibly-synthetic banjo on the bridge, or that the word "truck" puts in an auto-tuned appearance. As I listen to country radio, I constantly ask everyone in general and no one in particular whether this or that song's country or not, and even though that's not the only question, it's arises persistently.

Country music is two genres, really, and you’ll hear little of the first and all of the second on mainline country radio as you drive through America. The women need their own chart, because Jenny Tolman should have four #1 singles from her debut album There Goes the Neighborhood, instead of none. As I write, nine of the top 10 country singles and all 10 of the albums are by male artists. That's typical over the last five years, but still hits me wrong every time I check, especially because most of my favorite country artists of the moment are female.

American entertainment has always been somewhat gender-differentiated, and for decades there have been men's and women's novels, television shows, movies. It is a clash of genres as well as genders, and many couples of the 1990s or '00s worked an exchange: this Saturday night at the rom-com for next weekend at the action flick. To some extent it happens in music as well, of course, but this seems pretty extreme, a sort of apartheid of artists if not of audiences.

This summer has produced exemplary work in both veins. Steel Blossoms and Jenny Tolman issued debut albums that take up a distinguished place in a fully codified style established or explored by Miranda Lambert, Pistol Annies, Brandy Clark, Kacey Musgraves, Ashley Monroe, Erin Enderlin, Ashley McBryde, and Courtney Marie Andrews, among others. This is some of the best music being made now, and at summer's end the style's second supergroup (after Pistol Annies), the Highwomen (Brandi Carlile, Maren Morris, Amanda Shires, and Natalie Hemby), will debut on LP. Also, Lambert—perhaps the spearhead—is putting out singles again, gearing up for the follow-up to 2016's masterpiece The Weight of These Wings.

Thomas Rhett might be to the bros what Lambert is to the women, providing paradigmatic examples (both as a recording artist and as a songwriter for others) and influencing a cohort of artists. He makes some of the best records in this vein, even if I more or less try to avoid them. This summer he issued Center Point Road, which is about as good it gets in the bro mode. There has been a lot of this sort of stuff this year, much of it less distinguished than Rhett's work; I have trouble keeping the artists straight. Dan + Shay indeed. Kane Brown looks a lot more interesting than he sounds.

On both sides of the divide, gender identity is a dominant theme. The bros try to reinstitute or celebrate various traditional roles, and are liable to repeat such throwback sentiments as "You look so hot in those cutoffs! Slide over here, sweetmeat, and gimme some sugar" (try Kane Brown's "Lose It," Florida-Georgia Line's "Talk You Out of It," or Rhett's "Look What God Gave Her" if you insist on examples). They create a kind of nostalgic haze, or resolve to stick to some little zone in which girls and boys still act the way they did at a high school football game in 1986. They never let you forget that they're beer-swilling heterosexuals. The women are even more directly and extremely gendered, often declaring the power of sisterhood and threatening to lop off the heads of sexist assholes, or at least firebomb their trucks. Brandy Clark: "The only thing saving your life is that I don't look good in orange and I hate stripes."

Listening on either side, you get the feeling that whatever sex is conceived by the artist to be the opposite of their own consists of incomprehensible aliens. For the boys, the aliens are super-sexy little items who like trucks but make continual irrational demands (which is part of what makes them irresistible, for a little while anyway). For the girls, the boys are incomprehensible cheaters, for the most part. As in Big Little Lies, men are evil idiots, even when the women love them, and female solidarity is necessary for survival. This separatism is widely endemic to the culture as a whole at the moment: it's like the gender gap in politics, widening every day.

The girls and boys have some things in common, however. Both sides lean heavily on booze and weed. And maybe both sides are engaged in a rear-guard action, almost a nostalgia for sexual dimorphism. In some segments of world culture and pop music the gender binary is breaking down. But on both sides of the gender wall in country music, the differentiation appears more extreme than ever: men and women depicted as belonging to different species. In a broad sense, all these artists are gender traditionalists, which might be what country means now, insofar as it means anything in particular. The bros—unlike many contemporary guys—still date only girls, and the Pistol Annies and Highwomen are liable to be dealing with their ex-husbands in perpetuity. The men and women might understand themselves as coming from different worlds, and the music might sound extremely different, but they're inhabiting the same het and cis environment even in their conflict.

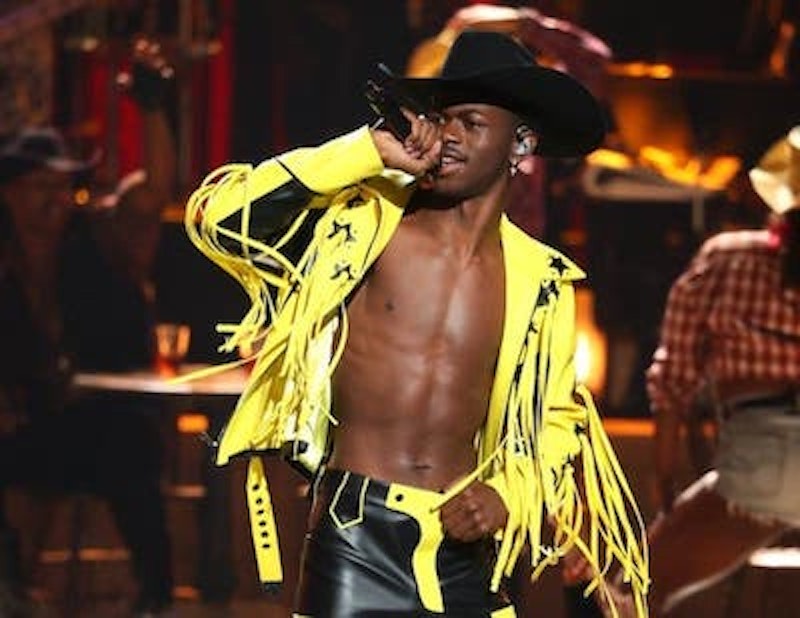

However, the bro consensus on the charts got smashed or ramified this summer with Lil Nas X's "Old Town Road," which kind of sent people into a crisis about what's country and what's not, and who or what is a bro, especially after Lil Nas came out as gay. As I write, the #1 country song on iTunes is "The Git Up" by Blanco Brown, and the very direct synthesis of hip-hop and country is, surprisingly and rather charmingly, commercially dominant. (The first time I remember thinking that this could actually work was hearing Gangstagrass' Long Hard Times to Come introducing the television show Justified.) I like this stuff a bit better than the average bro record; still, I think it's a phase or fad that's liable to be brief; it does alienate a fair portion of the country audience, for reasons not only racial or orientational.

Fad or not, however, maybe country hip-hop can help overcome the idea that genders are genres. It should be overcome, because both ways around it's getting exclusionary and both ways round it traffics in stereotypes. Each gender's songwriters tend to subject the other to caricature, as pretty little things in skintight jeans or as incomprehensible assholes. The connections don't appear to be fully human-to-human in either direction.

On the other hand, I'll miss the gender binary when it's gone, pathological though it may be, and I definitely want it to last long enough to get more records from Miranda Lambert and Jenny Tolman. But Bro country is played out. It's liable to get replaced for a little while by this hip-hop thing. And then, as excellent throwback-style albums by Justin Moore, Luke Combs, and Mac Powell have shown this summer, there’s liable to be a neo-neo-traditionalist backlash. Chris Stapleton outsells everyone, for God's sake, and after living for a year or two with Dan + Shay, you understand why. Things have seemed stuck, but they're going to look pretty different in a couple of years, I bet.

I'm not the only country fan who doesn't think Tim McGraw needs a vocoder, or the only one who thinks that there should be female singers on country radio.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell