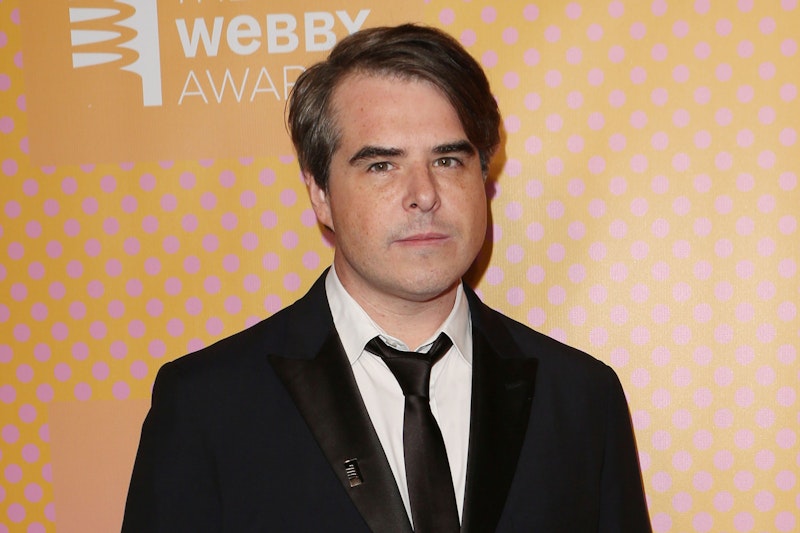

Ryan Schreiber is done: 23 years after starting Pitchfork Media in his parents’ Minneapolis basement, Schreiber’s “moving on,” but to who or what remains unknown. As soon as his exit was announced last week (in characteristically ostentatious fashion: an interview with himself via the “5 - 10 - 15 - 20” series, going over the most meaningful songs and records of his life), freelancers stalked the ground and danced and spit in the air, their bitterness still fresh years after rejected pitches and changed review scores.

I’ve read Pitchfork nearly every day since the summer of 2005, and its relationship with its readers has always fascinated me: never before has a publication been so ruthlessly mocked and satirized by its own audience. No one loves Pitchfork without reservations: “I check it for the news,” “I check it out of habit,” “I hate-read it sometimes.” This is all you hear, and that last one is key: Schreiber, for all of his bumbling (his John Coltrane review’s written in, uh, “jazz voice.” Shit, cat), was prescient, or at least lucky: he understood in the late-1990s that the Internet demanded daily content, that people weren’t going to pay once they knew they could get something for free, and that quantity always wins over quality. He embraced “hate-reads” before that awful idiom even existed.

Condé Nast bought Pitchfork in 2015 for an undisclosed sum, and in May 2017, Mark Richardson (former executive editor and second banana, who suddenly left the site a couple of months ago) said in an interview with Poynter that, “Condé Nast knew we had something successful and worked, and they didn’t want us to change the way we do things. The essential part of what we do hasn’t changed a lot, except hopefully being able to do it better, having access to better writers.”

But since the acquisition, Pitchfork has scaled back music coverage and started covering general pop culture: the Oscars, Stranger Things, and its ridiculous “October” sub-site, where artists are interviewed through a glass darkly about their favorite beers. Richardson continued: “I feel like Pitchfork’s mission has to do with reaching people who think music is not just something you put on that you enjoy, but it’s a way of life is going to carry it through.” CN must’ve seen things differently, and pushed this kind of content and coverage while scaling back daily reviews and doing away completely with track reviews.

Pitchfork might publish one throwback a year, like the recent Greta Van Fleet slam (still tame compared to their 90s and early-aughts reviews, when they gave Liz Phair, The Flaming Lips, and Sonic Youth 0.0’s), but the encroaching facelessness of the corporate conglomerate signals the end of an era, and Schreiber and Richardson’s unexplained departures without scandals indicates disagreements with CN. Maybe they actually are “lifers” who really did believe in the music and thought they could get away with major money and office space in One World Trade Center. Either way, none of the speckled spit from aggrieved writers will ever reach their windows now, if it ever did. Remarkably, they never had a major scandal: besides their shady and still undisclosed committee process of assigning scores to reviews without the writers’ control, Pitchfork weathered the collapse of the publishing industry with ease.

Schreiber could’ve had a much more destructive effect on independent music and indie/DIY culture: he was, and still is, an aloof Gen X snob who judges music and artists on criteria outside of the work itself. One of the few miraculous things about the streaming era is how egalitarian the culture’s become: no longer are death rockers forbidden from listening to Madonna, or indie stalwarts from enjoying Boston or ELO or—god forbid—The Smashing Pumpkins (Schreiber’s 1996 review of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, since scrubbed from the site, is a look into his typical Gen X mindset: “It's angst at its arena-rocking worst… The songs rock out like old metal, which wouldn't be so bad provided they could pull it off without over-commercialization.”)

Pitchfork couldn’t stop that change, but their rise happened to coincide with bands that embraced positivity, inclusiveness, holistic ecstasy, and a more accepting attitude toward major labels and commercial licensing. Arcade Fire, LCD Soundsystem, and Animal Collective never got down on other people for their taste, and as Panda Bear sang on Person Pitch (Pitchfork’s album of the year in 2007), “Take your head out of those mags/and websites that try to shape your style/take a risk just for yourself/and wade into the deep end of the ocean.” Another infamous scrub (since reinstated) is their pan of Animal Collective’s second album Danse Manatee, pulled from the site once they became favorite sons with Sung Tongs in 2004.

People mock Pitchfork because its pose is rooted firmly in 1980s- and 90s-zine culture, extremely cliquey and obtuse, resistant to outsiders and all those deemed uncool. But just as they exploded in popularity, so did the myth of the High Fidelity record store clerk. They propped up and made the careers of several bands, made some money, but their impact on the culture is hard to see today, if it’s even there. Pitchfork exposed me to many of my favorite artists, and I’m grateful for that. But otherwise, good riddance to the attitude: Schreiber’s game of playing favorites and slyly dismissing those deemed unworthy is so passé, and has been for over a decade.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith