Try to describe the career of Hawkwind and it sounds like fiction; a band from an alternate history invented by some stoned maestro of the New Wave of Science Fiction in a too-perfect description of the druggy post-Beatles haze. But they’re real, psychedelic warlords who make up a missing link between prog, proto-metal and trance, and they’ve got a new album out, The Road to Utopia. It’s mostly a re-working of their old standards, with a guest appearance on one song by Eric Clapton, formerly known as God to a generation of guitarists. It turns out that if God isn’t dead, he at least makes baffling decisions.

At first listen, The Road to Utopia is defiantly inessential. Hawkwind’s brought in one of the great rock guitarists to noodle some faux-blues over “The Watcher,” first recorded on 1972's Doremi Fasol Latido. Here the song’s bereft of the original’s brooding, threatening undertones. Like the other tracks on Road to Utopia, it sounds like a reinvention with a reasonable approach but indifferent execution.

Road to Utopia’s re-imagining of older pieces isn’t unprecedented. The band’s got a history of rerecording old songs in the studio in new styles, adding live recordings to a studio album, or dropping studio tracks onto otherwise-live albums. In this case the songs were arranged, orchestrated, and produced by Mike Batt. There’s an acoustic feel, which works particularly well on “We Took the Wrong Step Years Ago” (from 1971's In Search of Space), and overall this is perhaps as close to the bluesy rock of Hawkwind’s early years as anything they’ve done since. But songs like “Flying Doctor” still sound almost willfully pointless, compared to the originals.

That almost works for “Psychic Power,” a re-named version of “Psi Power,” like “Flying Doctor” off 1979's 25 Years On. What was a youthful boast of mind-reading skill here becomes regretful, as though years of staring into other minds only breeds despair. Still, Utopia is a swerve after their last two albums, 2016's The Machine Stops and 2017's Into the Woods. Narratively-linked concept pieces, those were electronic but also heavy; true space rock.

Look back further in Hawkwind’s career and things get complicated. Difficult even to list the almost 50 musicians who’ve played as an official member of the band, a wide-ranging group including (briefly, at one point) Clapton’s former Cream collaborator Ginger Baker and (at two other points) fantasy novelist Michael Moorcock. Over 49 years of existence Hawkwind’s released 31 studio albums, including Road to Utopia, and any number of compilations and live albums and compilations of live tracks.

One must step back and see Hawkwind as a kind of multi-dimensional sprawl, a shambolic concept art piece. Something like a beginning came in 1969, when a lineup crystalized around singer-guitarist Dave Brock, keyboard player Michael Davies AKA Dik Mik, and singer/flutist/sax player Nik Turner. Their self-titled album came out the next year, and by the year after that more long-time members had joined the fray: keyboardist Del Dettmar, poet-vocalist Robert Calvert, and the inimitable Lemmy Kilmister on bass.

The next few years formed a kind of classic period for the band. For most of the 1970s Hawkwind’s work was defined by the interplay of Brock and Calvert, whose satirical sci-fi visions blended into the band’s increasing experimentation with tape loops and electronic instruments. Lyrics melded high fantasy with psychedelia and occult weirdness; Calvert claimed the band’s big hit, 1972's “Silver Machine,” was based on an Alfred Jarry essay Calvert interpreted as being about a bicycle described as a time machine.

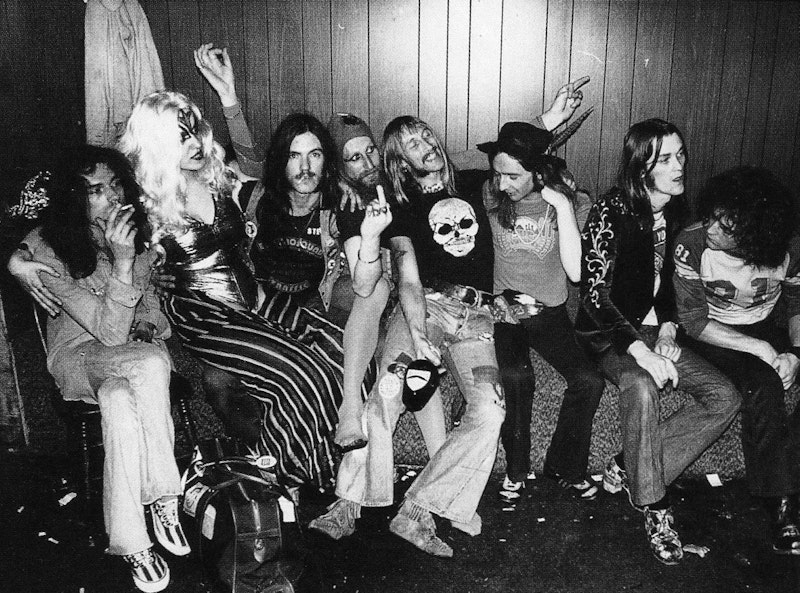

Unsurprisingly, Hawkwind also experimented with mind-altering substances. At one point the band’s manager estimated the band had been busted 68 times in three years. Nevertheless the police never found the heroin hidden in the bell of Turner’s saxophone. Lemmy recalled he and Dik Mik once took Dexedrine for four days, then Mandrax, then acid, mescaline, more Mandrax, cocaine and amphetamines before finally having to be helped onstage by roadies for a performance that would be recorded and released as part of an album called Greasy Truckers Party. Unfortunately, Lemmy would be kicked out of the band in 1975 for, he as he put it, “doing the wrong drugs.” He’d go on to form a new band named for a song he wrote for Hawkwind, “Motorhead.”

Calvert left the band in 1979, while Brock has remained the band’s guiding spirit, the sole consistent member in every incarnation of Hawkwind. A bewildering array of spin-off bands and indeed versions of Hawkwind under other names has proliferated: Hawkwind Light Orchestra, Church of Hawkwind, Psychedelic Warriors, Hawklords—which last alias was inspired by two novels from the mid-70s by Michael Butterworth based on concepts by Michael Moorcock, a kind of fan fiction about the band as post-apocalyptic rock-star heroes.

Under whatever name, Hawkwind’s best known as the chief practitioners of space rock. Warmer than Krautrock. Darker than psychedelic rock. Not as heavy as metal, and on average with fewer riffs per song. More organic than most electronica. Guitar, thumping bass, pounding drums, echoing vocals, and keyboards to throw in odd unnatural sounds and create a sense of empty sonic depth; a classic Hawkwind song tells us “Space Is Deep.” It’s not a surprise the band explored ambient and techno soundscapes in the 1990s.

Hawkwind’s an avowed influence on early punk groups—they recorded a version of their song “Urban Guerilla,” which the BBC had once refused to play, with Johnny Rotten. Yet much of their sound resembles early-70s Pink Floyd as much as anything, though prog fans have looked down on Hawkwind for a relative lack of rhythmic complexity. That’s not wrong, but their best and most frequently recorded songs, stuff like (say) “Brainstorm,” “Master of the Universe,” “Spirit of the Age,” and “Silver Machine,” often works through repetition. The sense of trance, even of ritual.

That’s reflected in their live shows, which over the years have boasted fire-breathers, lasers, sets, costumes, and dancers. One particularly statuesque dancer, Stacia, was considered a key element of the live show in the 70s, part of the band. Peter Hammill of Van Der Graff Generator, who frequently shared a stage with Hawkwind, as been quoted as saying, “the Hawkwind of the mid-seventies shows were very theatrical, but they weren’t slick. And I don’t think they were after putting up a slick show—or after perfection. To me it was more theatre in an agit-prop way.” Not surprising, then, that Hawkwind was a part of the free festival movement in the 70s and 80s.

Live or studio, to listen attentively to Hawkwind is to enter a trancelike state. Brock’s spoken about wanting to create the aural equivalent of an acid trip; you hear that. You hear the same songs returning on albums recorded years apart, familiar melodies repeating, but changed, like a recurring dream. It’s in this context that Road to Utopia is most effective, the latest set of changes rung on Hawkwind’s idiosyncratic but well-crafted standards.

It’s still not a conventional choice for an album. But this isn’t a conventional rock group.