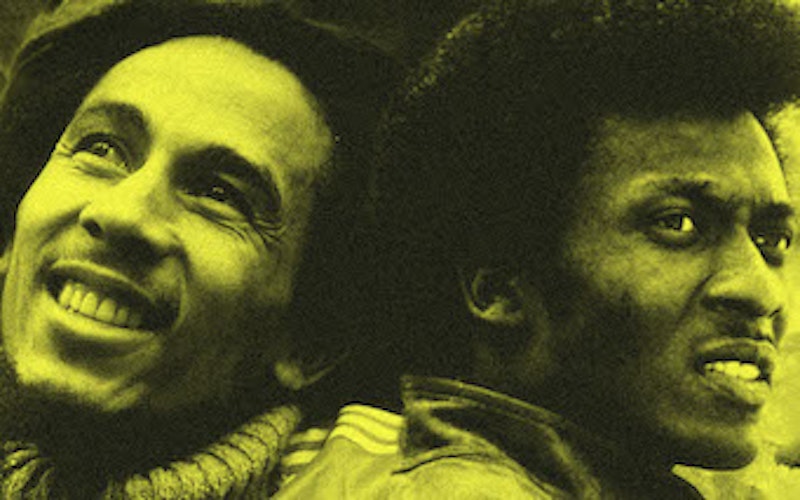

The other day I posted to Facebook a quote “from Jimmy Cliff’s manager, just before he was fired.” The quote, which I’d invented, was about this manager choosing (fatally, as it turned out) not to call Cliff’s Greatest Hits CD “Legend.” My Facebook friends were mystified, but my point was pretty simple: isn’t Cliff nearly as good as Bob Marley, when you come right down to it? If you’re looking for reggae milestones, it’s hard to do better than Cliff’s soundtrack to The Harder They Come. Marley’s career, meanwhile—like that of Billy Joel, or the Supremes—has to be measured in hit singles, not albums. Even Legend is half filler; in a recent survey of people who actually like and sing along to “Satisfy My Soul,” all of them were stoned. There are deep Marley cuts that don’t get enough airplay, like “Concrete Jungle” or “Natural Mystic.” But those are for diehards; they don’t explain why Marley towers so monumentally above everyone else making music on his island.

There’s more at stake here than reggae’s little civil wars, and more to the story than the way fads generally work. Whenever there’s a new trend, somebody gets lucky. Their celebrity snowballs, and they become an icon: Marley, dorm room poster child. But what Marley does on his very best songs is special. He writes them entirely in the present. They’re contradictory, like the “now” always is, hanging suspended between nostalgia for homes that have ceased to exist, and hopes for a future that isn’t promised. Take “No Woman, No Cry,” for instance, a song that women all over the planet know and love. It’s not misogynistic; it’s about “where we used to sit/in the government yard in Trenchtown... log wood burning through the night.” That place is gone, like the “good friends we had/and good friends we lost/along the way.” But Marley recollects a strange detail from Trenchtown: “The hypocrites/mingle with the good people we meet.” The song’s heart is right there, in the revelation that the good people and the bad couldn’t ever be disentangled; the beauty of a bonfire is enclosed, and placed in perspective, by the ugly government yard. There’s no way to stop yourself from falling in love and shedding your quota of tears.

“Never tell anybody anything,” Holden Caulfield concludes at the end of The Catcher in the Rye: “If you do, you end up missing everybody.” That’s love with a long reach, and it’s the kind of love that Marley’s music continuously kindles. It’s love for hypocrites and grimy concrete. He can’t forget, or even scold, the bad people he’s met. His songwriting is a conversation with God (the God of Christianity, as re-interpreted by Rastafaris) about how much love is possible. “If ye only love them which love you,” Jesus says, in the Book of Matthew, “do not even the [tax collectors] do the same?” That challenging question haunts Marley’s music. It’s maddening to him, like it is for Holden: “Love would never leave us alone,” he complains, grinning all the while, on “Could You Be Loved.”

For Jimmy Cliff, on the other hand, things are much easier. It’s like that old book rhyme: “Christ is my salvation/and Heaven my expectation.” That’s what Americans used to write (after their name) to indicate the books they owned: for some people, totaling their accounts brings Heaven immediately to mind. Cliff is that sort. Everything that needs fixing will be set to rights someday. “Hypocrite, you rotten hypocrite/you gonna pay the price someday,” he says, out of one side of his mouth; out of the other, he promises that “the harder the battle, you see/The sweeter the victory (now).”

There’s no uncertainty, just instant gratification: even on one of his very best songs, “You Can Get It If You Really Want,” Cliff’s impatience becomes exasperating. See how he added “now,” to reassure us, after the word “victory”? He also mangles his tenses to fast-forward the listener: “You must try, try and try, try and try/You succeed at last.” (On genius.com, the fan transcribing him makes the natural correction, writing “you’ll succeed at last.” It’s a nice bit of tidying. I wish that’s what Cliff had actually said, but it’s not.) There are epiphanies Marley doesn’t fully trust, so instead he asks questions: “Could you be loved?” “Won’t you help me sing/These songs of freedom?” Or Marley will suggest you “try the slums” of Trenchtown if you want to find music that really cures pain.

Cliff does the opposite. He leaps in with affirmations. “Now and forever, once and for all/Work your plan, you're number one,” he assures me. Whenever “Now and Forever” comes on the radio, I end up seeing Jeff Bridges, coked-up and clueless, singing Snap’s “I’ve Got The Power” at the beginning of The Fisher King. The chorus is four words long: I’ve got the power! Jimmy Cliff is surely right. I’m number one! What could possibly go wrong? All the bad feelings have disappeared.

When Cliff does have bad feelings, though, he admits it. I’ll grant him that much. He doesn’t just mourn; he despairs. “Tried my hand/At love and friendship/But all that is passed and gone,” he sings on “Sitting in Limbo.” The song “Many Rivers to Cross” is about knowing when “I can’t seem to find/my way over... I’ve been licked, washed up for years.” There are songwriters who give birth to the truths in their music; there are other songwriters, equally talented, who use music to drown out what’s real. What Marley creates, Cliff mostly runs from, his depression at his heels. Sometimes, I wish it was true that Cliff and Marley were equals. Sometimes, I wish that Bob Seger were really as honest as Bruce Springsteen. That way I wouldn’t know, now, what I didn’t know, then.

Sometimes I even want my despair to make me a hero of some sort, like Ivan Martin in The Harder They Come, who imagines an audience cheering him on while he exchanges bullets with the cops. On my better days, I like to put on “Wonderful World, Beautiful People,” by Jimmy Cliff. One thing bothers me about it, though. You know when he says, “Baby, we could have a wonderful world, beautiful people... But underneath this there is a secret/That nobody can reveal”? What is that supposed to mean? In any event, I pretend the crowd doesn’t hear it. I pretend there’s no secret—just a wonderful world, full of beautiful people. I pretend I’m not alone.