We're living in a musically bankrupt era. Audiences no longer care about authentic musicianship, or even about a "singer's" ability to carry a note. "Music" now is just an excuse for callow teeny-boppers to wallow in vulgar display and (virtually) naked provocation as some hot young thing slithers around the stage, wiggling and grinding in an orgy of bad taste and preposterous costuming.

A description of the performance style of Beyoncé, Katy Perry, Iggy Azalea or Miley Cyrus? Perhaps. But the scorn could just as easily be applied to Elvis Presley. As Joel Williamson documents in his new biography, Elvis Presley: A Southern Life, Presley's initial, volcanic popularity had little to do with his particular blend of country and R&B influences, and less to do with his singing style. Instead, Elvis was made the King by hordes of young, repressed, Southern female fans who used his concerts as an excuse for the expression of sexual desires they weren't supposed to talk about, or even have.

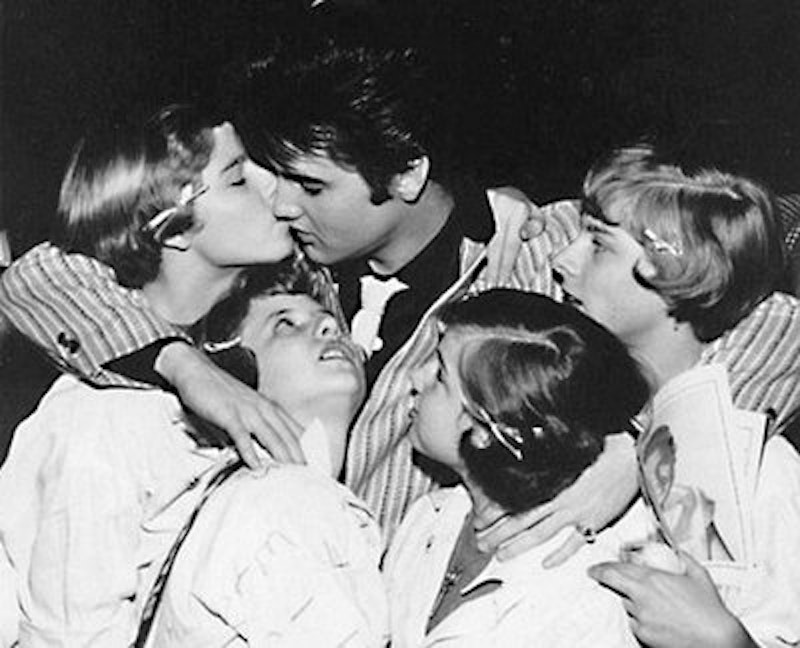

Elvis' appeal was not music, but lust. "He's just a great big hunk of forbidden fruit," one fan succinctly explained. At many concerts, girls screamed so loudly that "it was like... if you dive into a swimming pool—that rush of noise that you get…. It would be so loud that all you could hear in your ears was that sound," according to guitarist Scotty Moore. The band couldn't hear themselves play; certainly no one in the audience could hear a note. The girls didn't care; they wanted to see Elvis; the singing and the songs were beside the point.

And what was it they were seeing, precisely? That wasn't a secret. An Omaha paper said that Elvis' performance was "no more than a male cooch dance complete with bumps and grinds," while a Topeka paper said he "would put a burlesque queen to shame." Writer Paul Wilder also compared Elvis to a stripper, and said he "slunk panther-like across the stage with a masculine version of Marilyn Monroe's wiggle in every jerking step." Objectification was something that happened to women and to sex workers; therefore, if Elvis was being objectified, observers felt, he was a feminized sex worker. And since women and sex workers were, in this view, innately degraded, then Elvis was degraded too.

We like Elvis more these days—but that doesn't mean that we've embraced a link between art and sexual display, or somehow learned not to despise women or sex workers. Rather, critical appreciation of Elvis has been built around focusing on his singing and his music, rather than his dancing or uncanny ability to excite a (largely female) audience. Elvis is a genius in contemporary accounts because he's a great singer. And yet, as Williamson shows, it was the dancing and the sex that made Elvis into the King. Whatever Rolling Stone tells you, Elvis' singing, wonderful as it was, was not clearly superior to that of Sam Cooke, LaVern Baker, Clyde McPhatter or Lefty Frizzell. But none of them had Elvis' hips.

If Elvis' hips were used to denigrate him in the past, though, his critical standing now is such that it seems possible to recuperate not just the voice, but the lower body as well—and with it the lower bodies of other singers who aren't male, and/or white. If sexual performance was so central to Elvis' performance and art, why is it an artistic faux pas for sexual performance to be central to Beyoncé's art, or to Nicki Minaj's? Indeed, singers/dancers/sex symbols like Britney or Rihanna are more in the King's tradition than listen-to-that-guy-stand-and-play rock stars like Jack White.

Elvis' relationship with his audience also complicates the objections of some (though by no means all) feminists to the evils of pop sexualization. Ruby Hamad, for example, criticizes "the role of female pop singers in perpetuating women's objectification." Elvis is a pretty clear example that male pop singers (Justin Bieber?) can be objectified too, and that that objectification is not necessarily disempowering. Williamson writes that Elvis loved being a sex symbol, and identified strongly with the women who came to his concerts, who cheered him, and who tore all his clothes off whenever they had half a chance. "Always, Elvis' primary response to criticism was to make common cause with the girls in his audience," Williamson writes. Or as Elvis put it, "I've been scratched and bitten… I accept it with a broad mind because actually they don't intend to hurt you." Elvis loved being a sex symbol. Miley and Rihanna and lots of other female pop stars seem to enjoy it as well. Maybe they've been brainwashed by the man… but then, who brainwashed Elvis?

Elvis' audience also raises some questions about who's objectifying whom. Again, those audiences were mostly young women from a Southern culture that was heavily invested in ideas of female purity and asexuality. Elvis' female fans (and not just white female fans either, as Williamson emphasizes) used Elvis concerts as a way to assert, loudly, that they were sexual beings, and that they were going to objectify that guy up there on stage. The fact that pop music can be a forum for the expression of female desire should certainly be part of a conversation about, say, Blake Shelton or Robin Thicke. But it's worth thinking about in the context of performers like J. Lo, too, whose fanbase includes many (a majority of?) women. Most of these women presumably identify as heterosexual—but as Sharon Marcus has pointed out in her book Between Women, same-sex desire was a perfectly acceptable part of heterosexual female identity in the Victorian era, and (what with the pictures of fetishized women in women's magazines it remains so to some extent to this day. If female fans objectified Elvis as an expression of their sexual desires, why can't J. Lo or Beyonce's female fans be objectifying them for the same reason?

This isn't to say that objectification is always all good, or without its dangers. Williamson's book, like Elvis himself, tends to collapse and bloat in its later part, as the exuberant enthusiasm of released sexual energy in the early performances tips over into abusive, sybaritic decadence. Elvis is often criticized for appropriating black music. Whatever your take on that accusation, as far as moral objections go, it would be better to start with Elvis' apparently compulsive practice of statutory rape, his generally awful and controlling behavior towards the many women he slept with, and at least one instance in which he appears to have raped his wife, Priscilla, after she told him she was leaving him. Fame, sex, power and not least drugs led Elvis to some extremely ugly places.

The beginning of Williamson's book presents Presley as an exciting, generous, collaborator in desire. The longer, increasingly tedious end presents him as eaten up and hollowed out by his own ingrown, callow lusts for attention, sex and power. Young Elvis doesn't negate old Elvis, nor vice versa. Rather, together they're a reminder of how central sex has been to pop music, for performers and audiences of every gender.

—Follow Noah Berlatsky on Twitter: @hoodedu