It's easy to criticize misogyny in hip-hop when the music is taken out of its larger societal context. If middle-aged white women want to moan about rap lyrics—and especially if they start their rant with the groan-worthy qualifier "As a mom…" (which they always do)—then they need to address the question as to why their kids listen to this music in the first place. If Dr. Dre is a misogynist for releasing a song called "Bitches Ain't Shit," isn't little Aiden just as guilty for singing along? As bell hooks writes in her essay "Sexism and Misogyny: Who Takes the Rap?": "The sexist, misogynist, patriarchal ways of thinking and behaving that are glorified in gangsta rap are a reflection of the prevailing values in our society, values created and sustained by white supremacist capitalist patriarchy." Simply denouncing hip-hop as misogynistic is also an unconsidered—and slyly racist—way to delegitimize it as an art form. Music critics know this, and it's the reason that an album like YG's Still Brazy—which features the hypocritical, slut-shaming track "She Wish She Was"—can receive near-universal praise in an era when every blogger fancies themselves a critical theorist.

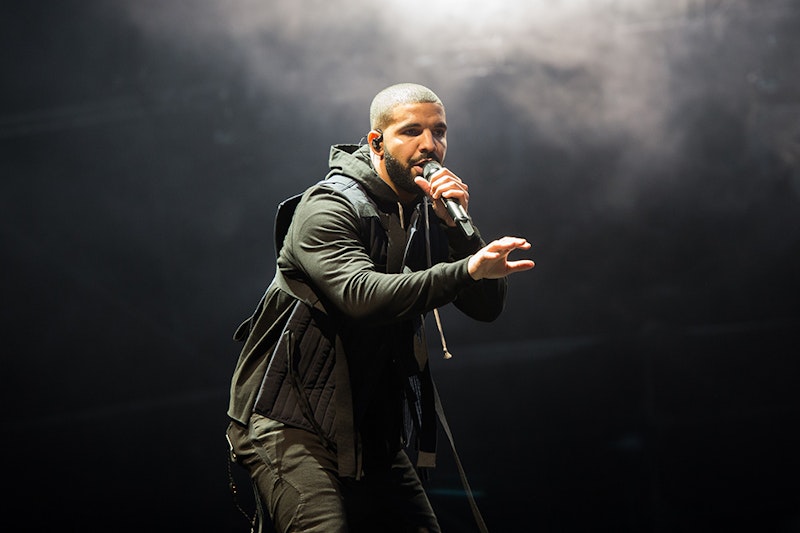

Why, then, is Drake so frequently labeled a "problematic" rapper by the same music critics who endorse Future, Young Thug, Kevin Gates or Gucci Mane?

In her 2015 op-ed "I'm Breaking Up With Drake," Meaghan Garvey wrote, "Drake is the chilling logical extreme of the beta male’s triumph over the last decade: the ultimate evolution of the nerd turned jock, […] who goes through women’s phones when they’re in the bathroom, firmly believes in the concept of the 'friend zone' at almost 30 years old, and surrounds himself with powerful women to sniff their hair until they become a legitimate threat to his own ego." She also criticizes the backhanded concern of "Hotline Bling" and the passive-aggressive specificity of naming Courtney from Hooters on Peachtree on record.

There's no denying that Drake's music has misogynistic themes, but he's fairly tame by hip-hop standards. "Hotline Bling" is a microaggression compared to Future's recent output, which was partly built on establishing himself as a hedonistic womanizer in the wake of his break up with Ciara. Despite this, Garvey is an outspoken member of #FutureHive. Drake might have trust issues, but he’d never rap, "I want no relations, I just want your facial/Girl you know you're like a pistol, you're a throw away" or "I ain't got no manners for no sluts/I'ma put my thumb in her butt."

Further, Dirty Sprite 2 functions as an album-length taunt at Ciara, one that revels in spite and malice; Garvey wrote a glowing review for Pitchfork.

I don't mean to pick on Garvey—she's a great writer, with a sharp ear for the funny and colloquial—for there are plenty of journalists who single out Drake as a misogynist. Every think piece written about his low-key sexism takes the tone of an exposé, though. Why is this news? Drake's been selfish and emotionally-manipulative since Jimmy Brooks' freshman year at Degrassi High. Besides the terrible punchlines, 2009's So Far Gone highlights the savior complex that people are only now criticizing. It's your fault if you mistook Drake for a nice guy.

Is his misogyny more nefarious because he couches it in faux-concern, because it's less violent and direct than his peers? No, of course not. But Drake—the former child actor, the bar mitzvah boy, the walking meme—is an easy target. Criticize him for appropriating his sound or crowdsourcing his lyrics, but don't single him out for misogyny unless you're prepared to tackle his peers, as well.