Few artists from the 1970s were as diametrically opposed as the Eagles and David Bowie. Ben Carson had nothing to say last week when Bowie died, but he attempted something close to emotion with this tweet: “Take It Easy, Glenn Frey, it's your turn for that Peaceful Easy Feeling. For the rest of us it's gonna be a Heartache Tonight #TheEagles.” The Eagles, even more than other blockbuster soft rock bands like Fleetwood Mac and Steely Dan, were the Goliath that the Davids of punk and new wave sought to destroy after 1977. There are certain songs I liked the first hundred times I heard them, but because of their constant exposure when they came out, they make my skin crawl now: songs by artists I like (“Boulevard of Broken Dreams” by Green Day and “Hey Ya!” by OutKast) and others I have no use for (“Hot in Herre” by Nelly and “Complicated” by Avril Lavigne). Those scourges lasted a year or two at the most, but I didn’t have to live through decades of “Hotel California.”

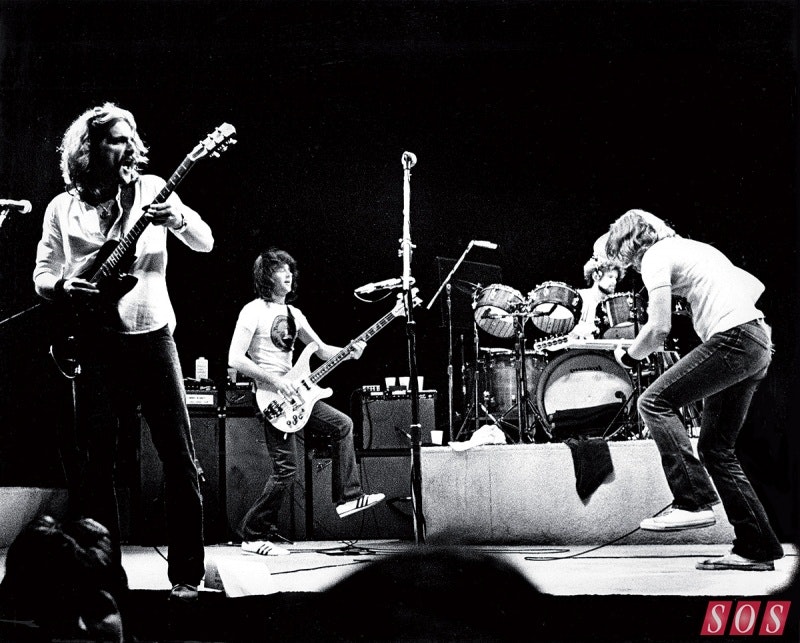

Good bass line on that one, but my god, I can’t imagine having to duck and dodge that six-and-a half-minute dirge for years on every radio station imaginable. Don Felder wrote the music for “Hotel California,” but Henley and Frey are responsible for the execrable lyrics. The only other Eagles song I know is “New Kid in Town,” a Frey composition, and I like it because I heard it on my own terms. A couple of years ago, I came across a live performance of “New Kid in Town” at the Capitol Centre in Landover, MD from 1977. I hadn’t heard a note of it before, and I was able to experience the song and the band without any cultural baggage or ossified memories of maximum rotation. I can listen to “Take It Easy” for the first time and fall in love with the vocal harmonies without resenting the Eagles for ruining radio and whoring themselves out to the great unwashed masses. Days before his suicide, Kurt Cobain famously walked by hundreds of fans lined up to buy tickets for the 1994 Eagles reunion tour and told his friend, “We might as well not have happened.”

But that’s never been my generation’s war to fight. In an era when calling someone a “sell out” means nothing and licensing your song for a car commercial is something bands strive for rather than scoff at, being a fan of a certain type of music or a specific band is no longer a political statement. The last great self-sustaining underground movement was the noise and experimental rock wave, beginning roughly with Fort Thunder in Providence in the late 90s and culminating in the final Whartscape in Baltimore in 2010. It was the same kind of network described in Michael Azerrad’s oral history of the 80s underground Our Band Could Be Your Life: bands and scenes in different cities across America making connections on their own through touring and self-releasing their records, promoting themselves on MySpace and Angelfire pages. Lightning Bolt, Animal Collective, Black Dice, Dan Deacon, Sightings, Arab on Radar, The Locust, Growing, Ponytail, and Prurient could fill warehouses, clubs, and eventually amphitheaters on the strength of their own PR and their hard work touring and recording constantly—no publicists or managers involved, for the most part. When Dan Deacon and Animal Collective sold songs to Crayola in the late aughts, they had to justify it, pre-empting any criticism by espousing how positive and impactful Crayola has been as a company. These days, bands that get television or commercial licensing are merely envied by their peers, not ostracized or smeared in Maximum Rock ’n’ Roll editorials. Suddenly, the Eagles make a lot more sense.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992