The last track on Amen Dunes’ Through Donkey Jaw is “Tomorrow Never Knows.” It’s impossible to tell whether it’s supposed to be The Beatles’ song or not. The pattering totemic spaced-out percussion seems to echo the more famous track… but it never coheres into an actual song. Instead, the psychedelia just spirals up and on, twisting and squeaking and swirling out over 10 minutes, the lyrics an inarticulate splash of half-heard phrases over layers of trippy reverb, tape loops, and spacey noodling. Structure is abandoned, knobs are twiddled, and— hey presto!—pop becomes avant garde.

That was the teleology of The Beatles themselves in a lot of ways—and also their legacy. Starting out with catchy jangly songs for teenagers they moved over the course of a decade to creating catchy, jangly songs for heavily medicated art openings. Certainly there was an outlier or two like the genuinely this-is-high-art-because-it-is-unlistenable “Revolution #9”, but for the most part the change from “I Want to Hold Your Hand” to “Strawberry Fields Forever” was a change of emphasis as much as anything. Art for kids a la Sesame Street became art for kids a la Paul Klee. White pop has turned itself into art not by transforming, but by becoming more like itself.

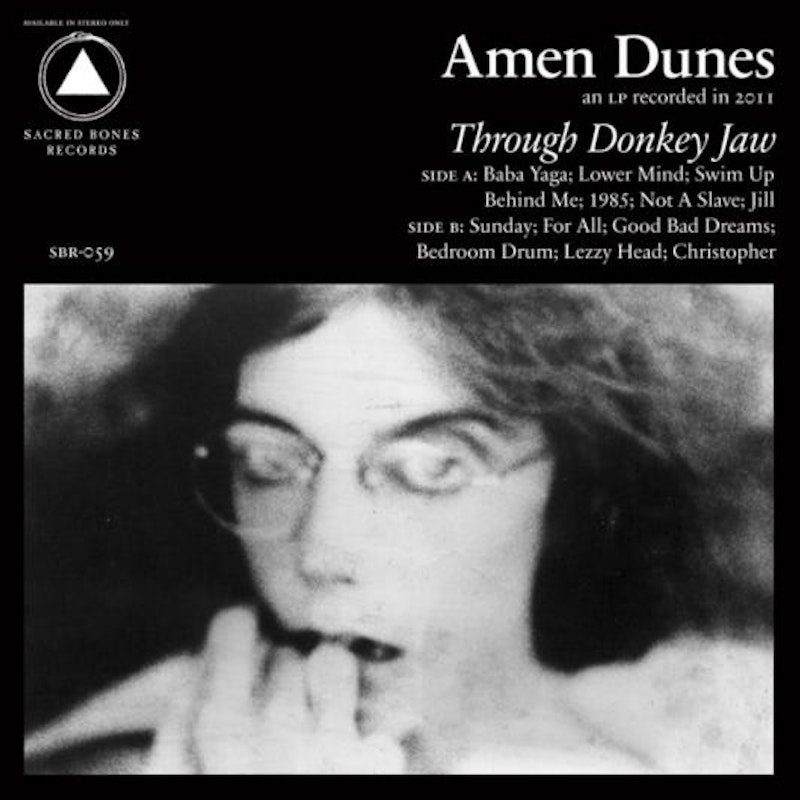

Amen Dunes (aka Damon McMahon) follows the blueprint faithfully. The first song on the album, “Baba Yaga,” sways gently over slooowed down chiming, half ual chant, with sawing dissonance on the very end. “Swim Up Behind Me” sidles even closer to a hook, the melody a gently echoing sing-along, like fairies whispering radio hits amidst the bowers. “Jill” has more krautrock spikiness; it’s pop fractured and staggered rather than pop slowed down and blissed out. “Sunday” uses a piano line that repeats over and over, as if to substitute the ingratiating repetition of the top 40 with the dry repetition of minimalism.

There’s nothing wrong with any of that, certainly. McMahon has studied Donovan, Brian Wilson and Skip Spence as well as The Beatles, and his album is tuneful and smart without drifting into the unbearable smugness that is the Fleet Foxes. Still, this isn’t the 1960s anymore, or even the 70s, and it’s hard not to think about all those predecessors while listening to this album. The Beatles were experimenting; they headed off into the sky with diamonds to try something new. Amen Dunes, on the other hand, is swooping through the trippiness because that’s the genre he’s chosen—at which point, you wonder, why not just give us a jangly, ingratiating round of “Please Please Me”? Is Through Donkey Jaws really different in kind from something like Under the Covers, the Matthew Sweet/Susanna Hoffs nostalgia-fest, filled with reverent recordings of the duo’s favorite 60s gems?

No knock on cover songs; I like the Sweet/Hoffs collaboration. Listening to it and Amen Dunes together, though, it becomes painfully apparent that by turning pop into art, The Beatles in some ways prevented their successors from embracing either. Maybe that’s part of the reason that, for all the sweeping influence of the band, Top 40 artists these days don’t really look to John, Paul, George or Ringo. Instead, they tend to get inspiration from folks like Michael Jackson, a figure who, for all his undeniable oddity, flirted only very elliptically with high art. Lady Gaga is certainly inspired by performance art in her costumes and videos, but there’s nothing avant garde about her music.

Meanwhile, Amen Dunes is never going to hit the charts—but somehow an older, attenuated pop clings to his high art gestures like a ragged day-glo concert shirt on a newly-minted zombie. If you want to be a pop star, you need to ditch the jangle for disco; if you want to be cutting edge, what are you doing mired in the 60s? But history has its own momentum, and a genre can keep on keeping on even when the references that defined it no longer make sense. Amen Dunes doesn’t want to be a pop star, like The Beatles, nor does he want to be avant garde, like The Beatles. He just wants to be The Beatles like The Beatles. And what the hell: as ambitions and albums go, he could have done a lot worse.