I didn’t grow up around the Grateful Dead. My dad had time just for Workingman’s Dead, and while my mom saw them a dozen times in the 1980s, she left the tie-dye and tailgating in California on the way to New York. Everyone always told me the live shows were the way in and that the records didn’t matter, so I didn’t hear The Grateful Dead, Anthem of the Sun, Aoxomoxoa, Live/Dead, American Beauty, or Europe ’72 until about nine months ago. I found my way into the Dead through their records, living with the songs in their platonic ideal—the jams finally made sense once I knew the bedrock character of the songs. Long Strange Trip, the new four-hour Dead documentary by Amir Bar-Lev, has arrived right on time. I love being a super-fan and finding new artists to explore and sink into once old obsessions have been worn out. There’s no better band to be obsessed with than The Grateful Dead: with thousands of bootlegs and so much variation from show to show, it’d take decades to comb through it all and exhaust it.

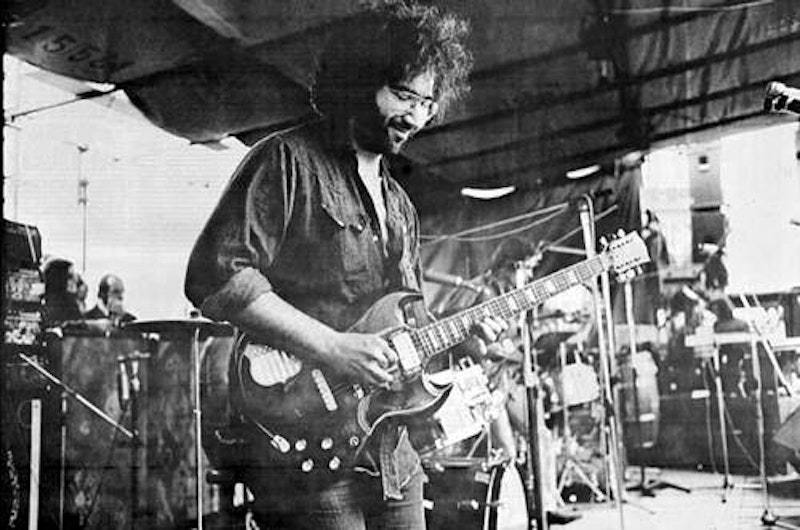

As someone says in the middle of the film, The Grateful Dead were defined by paradox: Jerry Garcia wasn’t interested in recording or archiving, yet the Dead became the most well-documented rock band in history. When asked by an interviewer what he thinks of Deadheads taping shows, Garcia responds: “I don’t care, it’s fine with me if people can find some use in music that’s already happened, that’s already been recorded.” The film uses the Watts Towers in Los Angeles and details an epiphany Garcia had at the foot of the immovable structures when he was in his early 20s: these monuments were frozen, dead, inaccessible. Garcia just wanted to play in real time, never stopping or getting stuck on one song, one lick, one approach, tracing and teasing death through his constantly mutating performances.

When he was seven years old, Garcia’s father died, and Bar-Lev speculated in a recent New York Times interview that, “I feel like Jerry was always keeping an eye on his future nonbeing from a very young age, and that’s one of the very useful things about the Grateful Dead, it’s a meditation on death… The more you think about death, the more committed you become to living in the moment. So it’s not accidental that he has this effusive, vibrant life force and also embodies a certain inevitable march towards death.”

Another grim irony that comes up as the band’s popularity explodes, and suddenly they’re filling stadiums, forced to tell tailgating Deadheads “DON’T COME IF YOU DON’T HAVE A TICKET,” among a dozen other “rules” publicist Dennis McNally forced the band to issue to fans—but Garcia passed the buck to someone else, so anti-authoritarian that he admitted to “self-sabotaging” the success of The Grateful Dead when he felt the “pernicious” power he wielded was dangerously close to fascism. He didn’t want to be a king. As the 1980s bore into the '90s, Garcia lamented that he “lived in a world without The Grateful Dead,” unable to leave his hotel room without getting mobbed by fans, hobbled by cocaine and heroin addiction, and unable to receive the rejuvenation and satisfaction that he gave his fans every night.

The film itself is a major achievement, easily one of the best music documentaries ever made. It has the same exhaustive attention to detail and refreshing aesthetic as Brett Morgen’s Kurt Cobain documentary Montage of Heck, but there isn’t nearly enough material to work with in Nirvanaland—at two hours, it was padded by an embarrassing animated sequence and a fascinating but frustratingly obscure selection of home movies that depict in vivid detail what everybody already knew: Cobain was an agoraphobic junkie smothered by success as much as his addiction. Long Strange Trip features over 1,000 photographs and unearthed video spanning Garcia’s childhood to his death in the summer of 1995, woven into an immersive and propulsive presentation that flies by despite its epic length.

The first half of the movie follows a typical Behind the Music trajectory: early trauma inspiring fevered dedication, timing, and the good luck of five superb musicians with distinct influences coming together to form something larger and more powerful than the sum of its parts. Surviving band members Bob Weir, Phil Lesh, Bill Kreutzmann, Mickey Hart, and Donna Godchaux all appear, along with former tour manager Sam Cutler and McNally. A mantra is repeated throughout the film by everyone involved: “fun.” The same spirit that made them largely eschew the studio and radically change setlists every night was also an inadvertent abdication of responsibility: as keyboardist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan descended into suicidal binge drinking, Cutler says that he saw the band do nothing to help their friend get out of the muck. The fun must go on.

The film’s second half is considerably darker, and Bar-Lev paints a haunting portrait of a man burdened by his own success, unable to stop touring at the expense of his bandmates, their massive crew, and all their families. When “Touch of Grey” became a surprise hit in 1987, the machine only accelerated, and despite falling into a diabetic coma in 1986, Garcia never took another break, continuing to tour until his death. The Grateful Dead opened their last show ever on July 9, 1995 with “Touch of Grey,” another irony: a defiant song about survival and melancholy. Garcia misses half the words, and can barely croak the refrain “I will survive.” The studio version is a masterpiece, a driving song brimming with hope and life. To me, recording and the platonic ideals of songs are infinitely more satisfying than the draining and ultimately ephemeral experience of playing live. The Watts towers that Bar-Lev returns to throughout the film are a perfect metaphor for what I love about recorded media, but the idea of eternal, unchanging monuments was anathema to Garcia.

The Grateful Dead remain one of the most polarizing rock bands in history, and the greatest praise you can give Long Strange Trip is that people who hate the Dead will find themselves enthralled. In Variety, Owen Gleiberman wrote, “For the first time, it made me see, and feel, and understand the slovenly glory of what they were up to, even if my ears still process their music as monotonous roots-rock wallpaper.” Bar-Lev has succeeded in making a film that’s open and appealing to everyone because he came from a critical place of a super-fan: “For me, being picky was a way of enjoying the Dead and participating in it, much as sports fans perennially complain about their team… I don’t like the tribal aspect of Deadheadism, I don’t like the saggy fonts they use. Much of the marketing feels like it could be about a monster truck rally. It’s too bro-oriented.” Too often super-fan documentaries fall into fawning and rosy-eyed visions of their subjects—there is no sentimental “Uncle Jerry” nonsense in Long Strange Trip. Bar-Lev has managed to weave warehouses full of archival material into a cogent and beguiling film far from hagiography, but still so full of love, enthusiasm, and empathy for everyone involved.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992