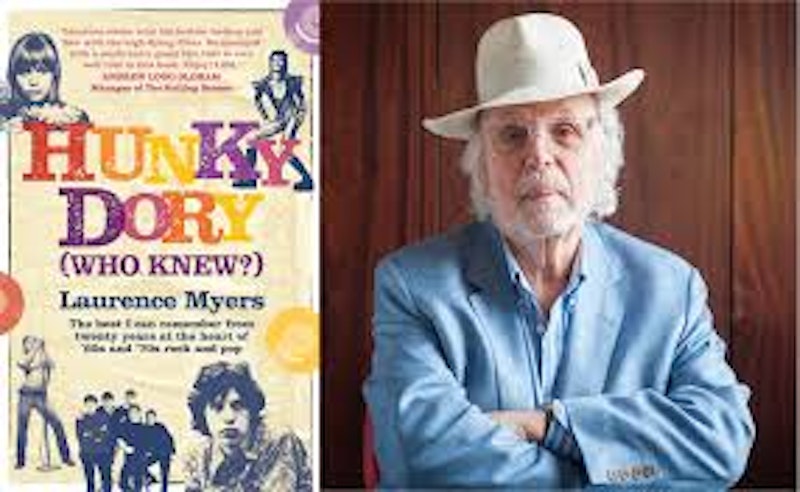

We’re at peak rock memoir. Nearly every living legacy artist (and some dead; see Prince) is having his or her say on paper. The top tier of these has exceeded expectations: Keith Richards’ Life was widely acclaimed, and Patti Smith’s Just Kids notched a National Book Award. But relatively little has been heard from the music industry insiders who helped shepherd the rock era into existence. Laurence Myers’ new Hunky Dory (Who Knew) joins recent efforts by Clive Davis and Danny Goldberg in attempting to correct the imbalance.

Laurence who? you may wonder. Even as a David Bowie fan, I drew a blank. There’s no Wikipedia page on Myers, and scant information available online. But reading Myers’ entertaining, self-effacing account of his Forrest Gump-style journey through the major events of rock history, I came away wondering why he’s not a household name. In addition to being at ground zero in the creation of Ziggy Stardust—the album and persona—Myers had significant interaction with The Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Animals, Stevie Wonder, Iggy Pop, and Marianne Faithfull. In his later career as a film and theater producer, he worked with Anthony Quinn, Jacqueline Bisset, Peter O’Toole, and Jane Seymour on various projects, and executive-produced the recent award favorite Judy starring Renée Zellweger. (He also had a hand in something called Bloodbath at the House of Death.)

A trained accountant, Myers stumbled into the entertainment world via some early work managing the books for legendary music producer Mickie Most, who in turn opened the door for associations with infamous Stones/Beatles manager Allen Klein, future Led Zeppelin manager Peter Grant, and others. Leveraging his connections with these men and the musicians they managed, he quickly transitioned over to the artist representation side, and it’s likely that without his early championing (and bankrolling) of Bowie under the auspices of his GEM production company we’d never have heard of him.

The book shares its title with one of David Bowie’s most acclaimed albums—not coincidentally a project Myers funded—and it’s clear that Myers’ role in Bowie’s success is his proudest achievement. But there’s more to the story—so much more that Myers good-naturedly advises readers to skip the early chapters if they’re only onboard for the rock material. Anyone who takes him up on that, however, would miss out on the author’s vivid account of his working-class Jewish environs in post-World War II England—the incubator of his relentless drive. He contrasts his hard but supportive upbringing with that of Allen Klein, whose early life had been upended by family tragedy and an extended stay in a Hebrew orphanage. Myers surmises that this was the root of Klein’s Machiavellian business style, which he implicitly contrasts with his own more genial approach. These nuanced observations of Klein, who’s often caricatured as a money-grubbing scoundrel, are some of the most insightful I’ve read and go a long way in illuminating why John Lennon—also of a broken family background—was unique among the Beatles in never losing affection for Klein.

The early chapters establish a theme that runs throughout the course of the book: a fondness for schemes that walk the fine edge between legitimate and something else, and how that sort of parsing is a key aspect of the entertainment industry—and indeed successful business in general. In Myers’ specific case this began with a stint at “market grafting”—hawking wares of somewhat dubious origin at the Sunday street market on London’s Club Row Waste. Myers’ stock-in-trade was “mainly old confectionery” delivered to him in the middle of the night by “a man only known to me as Cecil... This was before the concept of sell-by dates, which is just as well, because most of my stock would have had Roman numerals.” He fondly recalls his market employee, a man known as “Chicken”: “I went to his wedding to a hooker who was pregnant with twins. Chicken proudly claimed that ‘one’s mine an’ one’s me mate’s.’”

It’s not too great a leap from characters like Cecil and Chicken to music business personalities like Klein, Don Arden (famous for allegedly dangling Bee Gees manager Robert Stigwood out of a fourth floor window during a business dispute, and also for siring Sharon Osbourne—but not during the same incident) and Peter Grant. And Myers elucidates a theory about the “dishonors” to “honors” trajectory that most of these types follow:

It is said that there are three phases in a businessman's life. “Dishons” is the time when you do things that you would rather not, in order to get on; “Hons” is when you want to be regarded as an honorable, 'his word is his bond' type; and “Honors” is when you want to be recognized with some glory—be it a knighthood or being enrolled in the Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame.

Which leads us to David Bowie, who hewed as closely to this formula as anyone. When Myers is first introduced to the singer via Myers’ acquaintance and future business partner Tony Defries, we get the impression of two old-school grifters sizing each other up. Bowie was never short on attention-grabbing schemes, yet readers who’ve not delved too deeply into his story may find some of Myers’ observations surprising. His David Bowie is quiet and tentative, awkward onstage and reserved off—a “low-energy individual.” (How such a person managed to have a sex life that approximated the Emperor Caligula’s is a bit of a mystery, but we should never underestimate the allure of mismatched eyeballs). But the erstwhile David Jones’ songwriting talent was immediately obvious to Myers. As for the taboo-pushing “Ziggy Stardust” persona, Myers gives a lot of credit to Bowie’s brash American wife Angie for encouraging her husband to either go big or go home. Myers himself didn’t initially grasp the appeal of flaunted androgyny but wisely heeded Bowie’s assertion that he knew what he was doing. We know the rest: Bowie found his confidence and his voice, upended social mores, made a ton of money, and changed music history. And Myers got to tell his friends, “See, I told you so.”

The GEM patronage seems to have provided the best of all possible worlds for the up-and-coming star. Myers admired Bowie’s ability to write intelligently on subjects outside the typical pop music parameters, he trusted in the songwriter’s long-term vision (and prospects), and gave the young artist the perfect gift: generous financial support coupled with creative freedom. Less tangible but perhaps just as important was the stabilizing influence of Myers’ personality. Somewhat unique in Bowie’s circle of friends and colleagues, Myers was happily married (and monogamous), an attentive parent, and not a drug user. Angie later told Myers that he had been “the most honest man that she had ever known in the music business, with a wife and family that gave stability,” and that she and David had missed his “steadying influence” after they decamped with Defries to America.

Perhaps unbeknownst to Myers, Bowie harbored a conventional streak at odds with his more outlandish impulses and always seemed to function best when these two sides of his personality were at détente. It’s probably not a coincidence that the GEM period was Bowie’s most impressive early creative stretch (the writing and recording of the classic albums Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust), and that Myers’ selling off his interest in Bowie to the brilliant but less grounded Defries marked the beginning of a prolonged downward spiral—personally and business-wise, if not creatively—for the singer.

This is all compelling, so I feel a little embarrassed in noting that Laurence Myers isn’t a great writer and Hunky Dory isn’t a great book in any kind of conventional sense. Some readers will find it meandering and chronologically arbitrary. And not all Bowie/Stones/Beatles fans will find the detours, such as Myers’ stewardship of the New Seekers or his erratic ride through the movie business, as interesting as I do. But there’s an X factor—something about the man himself—that carries it along. Myers is someone most people would enjoy having over for dinner. He has the right mix of charm, eccentricity, and joviality, and is both larger than life and humble. Most endearingly, he seems to have never lost his wide-eyed affection for the world of show business. He’s just too likable for anyone to begrudge him his success—”dishons” and all. Hunky Dory won’t be awards fodder and it’s not likely to show up on any critic’s Top 10 list, but I immensely enjoyed this book.