Southern music journalist Stanley Booth made his mark with The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, his account of accompanying the British rockers on their infamous 1969 tour, culminating in the Altamont debacle. Born in Waycross, Georgia and based in Memphis these days, his newest offering, Red Hot and Blue: Fifty Years of Writing about Music, Memphis and Motherf**kers’ (Chicago Review Press), puts his first-hand familiarity and respect for the bluesmen who shaped his world on full display.

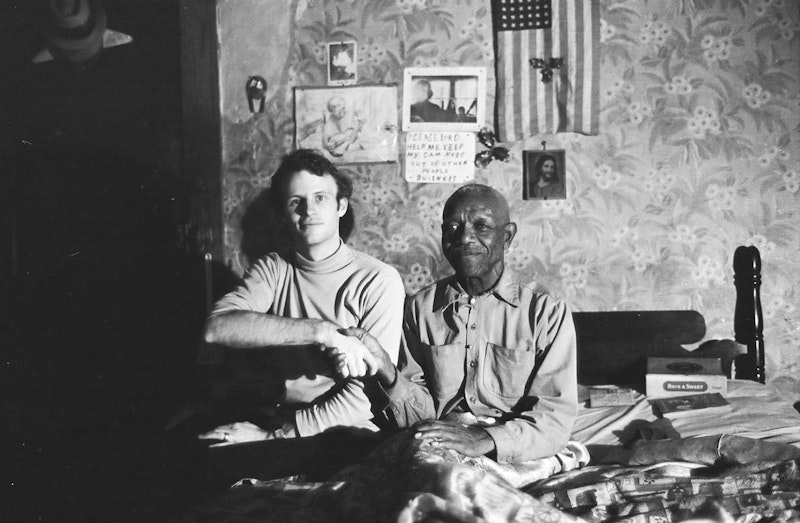

Booth gives detailed portraits of his friend Furry Lewis, famously memorialized by Joni Mitchell in “Furry Sings the Blues,’’ a one-legged wonder reduced to sweeping streets in Memphis and playing the occasional gig in thinly-attended coffee houses by the time Booth befriended him.

“No… all these years, I kept working for the city, thinking things might change, Beale Street might go back like it was,” Lewis tells Booth, an interlocutor savvy enough to stay out of the frame when he realizes he’s hit conversational gold. “But it never did.”

“But you went on playing.”

“Oh, yes, I played at home. Sometimes, nothing to do, no place to play, I’d hock the guitar and get me something to drink. And then I’d wish I had it, so I could play, even just for myself. I never quit playing, but I didn’t play out enough for people to know who I was. Sometimes I’d see a man, a beggar, you know, playing guitar on the sidewalk, and I’d drop something in his cup, and he wouldn’t even know who I was. He thought I was just a street-sweeper.’’

The collection also includes indelible portraits of Otis Redding fooling around with the initial version of “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay’’ at a Memphis studio just before his fatal plane flight, and the Bar-Keys, the back-up band who lived and died with him. Booth hangs out with Mose Allison after the Faulknerian pianist/songwriter turned 70, eliciting a wry response when he asks what Mose thought of The Who’s “Young Man Blues’’ cover: “I got a check in the mail for $7,000. I thought, ‘Man, what the hell is this? This must be some mistake.’”

Along with the likes of Elvis Presley—whom he chronicled for Esquire with a lead that was cut about Elvis performing an intimate act on Natalie Wood—and James Brown, Booth celebrates lesser known musicians like Bobby Rush, of whom he writes: “Bobby Rush, in his mid-sixties, continues to make first-rate R&B records and to have the best stage presence since Ike and Tina broke up. If my friend Mick Jagger were hip enough and wanted to revive his career—instead of endlessly dragging his scrawny ass around the planet, endlessly regurgitating his greatest hits—he would cut Bobby Rush’s ‘Jezebel.’”

Mick, apparently, misplaced the memo. But Booth is undaunted.

“Blues for the Red Man’’ pays homage to Memphis musician C.F. Freeman III, who jammed with greats like Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn when they were playing joints like the Rebel Room in Osceola, Arkansas, separated from the audience—and flying debris—by chicken wire. The piece, like many here, ends in a funeral, which Booth attends, accompanied by Sam The Sham, of “Wooly Bully’’ fame.

“When Freeman was good, he was the best, when he was bad, he was the worst,’’ said Sam. “If all the people were pallbearers who wanted to have that honor… the handles on this coffin would be a mile long.”

Historical essays on Ma Rainey, New Orleans cornet king Joe Oliver and Blind Willie McTell are thoroughly researched while avoiding academic dust—Booth has a knack for the telling anecdote, including the perhaps apocryphal claim that folklorist Alan Lomax acquired the rights to McTell’s work, since celebrated by Dylan and countless others, for a grand total of $10.

There are lapses here—a lengthy account of the travails of Presley’s physician, “Dr. Nick,” accused of overprescribing to the star in ways that presaged Michael Jackson—reads like a defense brief, and an unconvincing one at that. And some of the pieces here, including “Fascinating Changes,” a masterful profile of the late, great, emotionally disturbed jazz pianist Phineas Newborn, Jr., are repurposed from his earlier collection, Rythm Oil: A Journey Through the Music of the American South. And inclusion of a putative screenplay on the Memphis blues scene commissioned—but never aired—by Cybill Shepherd seems like filler.

But when Booth sticks to the music, he can’t be beat. He dedicates this volume to Dewey Phillips, the wild man disc jockey who played Elvis Presley’s first tunes, “That’s All Right, Mama’’ and “Blue Moon of Kentucky’’ 30 times on WHBQ in Memphis, then turned down the chance to be Elvis’ manager, leaving room, unfortunately, for “Colonel” Tom Parker.

The name of the show was “Red Hot and Blue.” Of course.