I was riding the bus recently, half listening to N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton, half reading a newspaper. At some point I semi-consciously decided to change the N.W.A., mostly out of a habitual tendency to aimlessly scroll through my iPod music library. And scroll I did, idly looking for the next choice, during which I realized I hadn’t really been able to hear N.W.A.’s furious opening title track over the whirr of the bus engine and the intermittent whine of the brakes. Before I had the chance to think more about it, my thumb had semi-autonomously moved to Jenny Lewis’ Acid Tongue, which I don’t particularly like. I frowningly watched my finger push the Ipod's center-button: Jenny Lewis, Acid Tongue, then...WHAM!

My head jerked back and my back sprung out of its slouched posture. Acid Tongue, which I remembered being gentle, if occasionally teeth-baring, country rock, had just blasted into my ears, cutting effortlessly through the sounds of the bus. I hadn’t touched the volume at all—how did the frolicsome Rilo Kiley singer so effortlessly out-thunder N.W.A.?

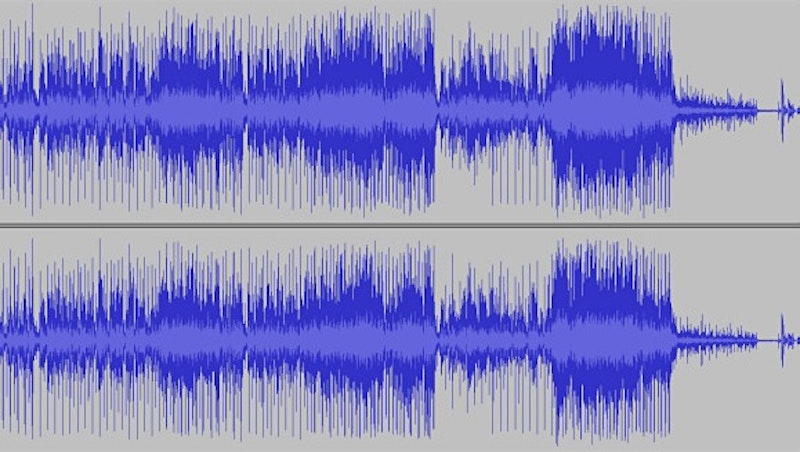

The “loudness war” has been raging since the introduction of the compact disc in the 80s. The driving force behind this phenomenon is a belief among record companies that the louder a song is, the better it will sell. As a result, music on CDs has gotten louder and louder over the past two decades. Straight Outta Compton was released in 1988. Acid Tongue is from 2008.

But more importantly, the dynamic range on the average album has greatly decreased in parallel. This means that the average difference, the range, between the loudest and softest sounds has been greatly diminished. This compression means that all parts of the mix are jacked up, and the resulting music is almost constantly loud. According to sound engineers, this is literally tiresome for the human ear. Some contend that it may lead to aggression.

I have my doubts about the aggression-causing power of compression, but have noticed my own fatigue when listening to certain albums. Californication from the Red Hot Chili Peppers is a good example. Queens of the Stone Age’s aptly titled Songs For The Deaf is, too. Iggy Pop's 1997 re-master of Iggy & The Stooges' Raw Power is awesome, but it gives me a killer skull ache, especially on headphones. After the N.W.A.-Jenny Lewis debacle, I remembered why I hadn't liked Acid Tongue so much. Upon first listen I had found the rustic songs themselves pleasant, but the production struck me as ridiculous. The juxtaposition of folksy humility and bright, in-your-face sound was straight-up funny, almost self-parodying. Outside of that, the music felt flat and dead, despite its tendency to jump out of the speakers.

In light of all this, some speculate that the return to vinyl is not just a hipster status move. The limitations of the vinyl medium itself prevent the extreme compression and loudness that CD's allow. CDs have always been something of a double-edged sword; they are great because they have far greater dynamic range than preceding media, capable of bringing sound quality closer than ever before to that of a live experience. On the other hand, this greater dynamic range means that the loudest highs are louder than on any medium before. Vinyl may have less dynamic range, and therefore be overall less capable than the CD, but, in practice, modern music mastering doesn't take advantage of the CD's greater dynamic range—only of its capacity to be the loudest. That's the real shame. What could therefore be the audiophile's wet dream is his nightmare, so he'll have to keep turning to vinyl, which at least isn't affected by the loudness war.

But the debate and frustration of sound engineers has existed since this loudness war started. In an article on the loudness war now several years old, two sound techies are quoted giving their opinions on the loudness war's origins:

"Ours is a service business," Tubb says. "If that's what the client wants, I try to explain the trade-offs in clarity. In reality, we're just trying to accommodate requests from labels or A&R guys or the artists themselves. They'll walk in with a handful of CDs and say, 'I want it to be as loud as this one.' The last five years it's gone absolutely mad." "Ask any mastering engineer which they prefer," Wofford says, "Something that's super-compressed or not compressed. But they keep their mouths shut about it if they want to keep working."

I'm a sucker for the drama. I like the image of the maverick producer, toppled from his comfy stool before the mixing boards for telling the truth. Now he's on the run from his own, who want to keep him from further spreading the truth of compression, to keep him from biting the hand that feeds the rest, or something.

That aside, it seems that the loudness war is a result of pressure from above, from the labels, and not so much from producers. And so it is now a growing group of producers, with essential support from listeners and musicians, who are rebelling, calling themselves the Pleasurize Music Foundation.

The foundation was founded in January 2009, and their initiative begins on April 1, following a rough model of organize, inform the masses, and then take it to the streets/the big man’s doorstep. The organization is already there in the form of the website and stated aims. Next comes informing the casual music listener on the issue, and on how to better recognize over-compressed dynamic range. The last and biggest step is to get record companies to agree to a gradual yet comprehensive overhaul, whereby they would fully kick their compression addictions by June 2010. Ideally, all music would be released with a dynamic range rating stamp. The PMF maintains that a rating of DR14, meaning a dynamic range of 14 decibels, is more or less perfect. The re-mastered Raw Power, by comparison, has at times a dynamic range of merely four decibels, and is cranked up so loud that it often clips.

I agree with a lot of the ideas behind this initiative. Modern music is often mastered too loud, and it’s not even necessary to do so. The recent consumer uproar in reaction to the super-compressed, super-loud Death Magnetic by Metallica, proves that the driving idea behind it all—the louder, the better the sell—is straight-up false. It seems to me that the loudness war is now a relic of a time when big record companies completely dominated popular music. But this cold war is drawing to a close. Hundreds of small bands have, through cheap online marketing and press coverage, been able to cultivate serious followings. And their similarly small record labels often release only their pre-recorded material, rather than put the band up in a studio to record a new album. That means that these bands are not only reaching significantly more people via cheap online media, but that the most important aspect of the band, their music, is also “cheap,” and therefore likely not super-compressed by sound engineers.

Over-compression is not only unnecessary, but it may lead to an undesired radio sound, thus potentially harming the music’s saleability. Radio stations already compress everything they broadcast, in order to assure equal volume levels on all of their content. This means every modern song is effectively double-compressed for radio play, which causes further distortion and clipping.

I have, however, a lot of questions regarding the language on the PMF's website. The entire issue gets messy as soon as qualitative value assessments are tacked onto quantitative measurements of loudness. How can PMF sweepingly state that the loudness war makes listeners "aggressive"? Does the PMF's initiative merely seek to provide indication of loudness and compression, or does it seek to indicate if music is too loud, and too compressed? Is it possible to do the former without doing the latter?

And what does “too loud” even mean? I fear that the PMF may potentially be just as homogenizing as the loudness war. If the labelling of music volume gains currency, what is to stop the PMF's connotation of aggression-inducing ability from gaining currency, too? What if that connotation were extended into the realm of health—compressed, loud music being seen as unhealthy? In the worst case, this could be enabling—another cause for some radical group of parents to bulldoze piles of CDs on Main St. and lobby for "aggressive, violence-inducing" loud music to be banned.

I am also not entirely convinced that the PMF's efforts wouldn't be superfluous. With the uproar in reaction to Death Magnetic, which resulted in petitions for re-mastering, and with the declining market control of major record labels that have fuelled the loudness war since its beginnings, I’m not sure that the most extreme, undesirable aspects of over-compression won't lose prevalence on their own.

To come back at last to Iggy Pop: I wouldn’t want anyone to tamper with his mix of Raw Power, or to stigmatize it with a "too loud" rating. Sure, I know it is ear-splitting, and I might lose my hearing by 40 if I listen to it too much, but the loudness is an integral part of the album's sound, and so too is loudness integral to many other albums.

While I believe that PMF sound engineers probably have nothing against hard, heavy music, their loudness-controlling efforts may be misguided, and therefore easily misappropriated by those who do, to censor such music. If you still don't believe that there are people who would seize an opportunity to cry foul against loud music, keep in mind that the PMF's dynamic range rating would be applied worldwide.

I agree: the loudness war needs to end. Over-compression can be obnoxious and rob music of its charm. But it has its place, and trying to regulate it could ultimately lead to it being unfairly and irreversibly judged, or worse, censored.

Songs for the Deaf

Inside the music industry's "loudness wars," including the leading opposition movement that may be our only hope.