The subversive rise of Bob Dylan, which in the 1960s saw a kid from Minnesota infiltrate the folk scene and then, in one blow at Newport, rip its heart out, is hard to imagine happening again. The landscape has changed. Revolutions can still be made in music, but to uproot perception as thoroughly as he did, we’d have to be talking about a different industry, one that actually had roots.

But if you were going to find the next Bob Dylan, you’d probably have the most luck locating him or her in hip-hop, the Wild West of the contemporary music scene, where any kid can stake out territory with a self-made mixtape and a Twitter account. Hip-hop also happens to be the site of the most creative, engaging new music, which doesn’t hurt either. Instead of the next Bob Dylan, though, what we’ve got is the next genetic Dylan, after Jakob: the next Dylan to make music.

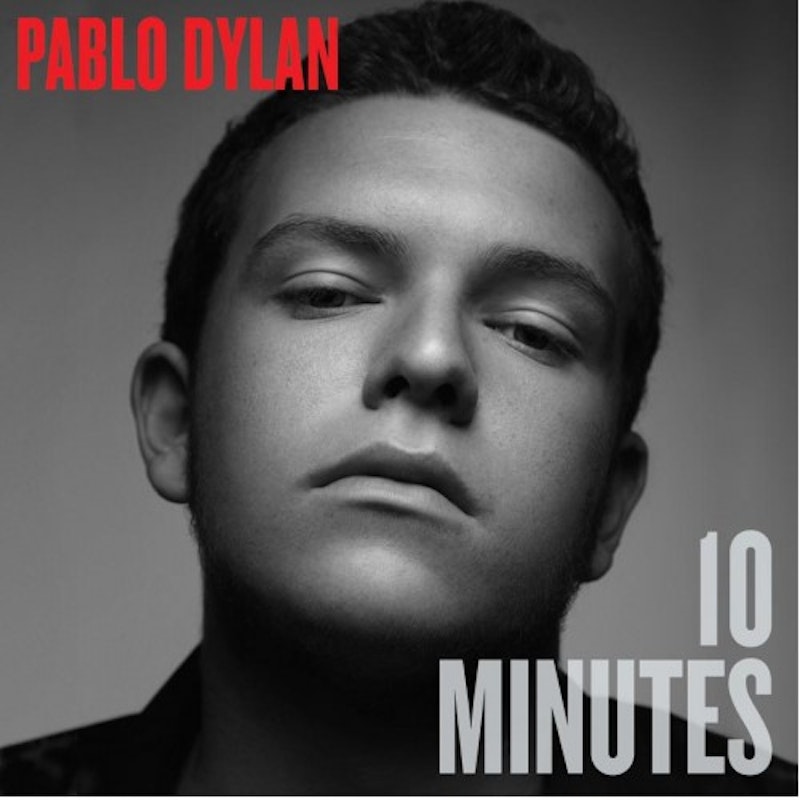

Pablo Dylan is Bob’s grandson. He just released a mixtape, called 10 Minutes, and a single, “Top of the World,” that’s been getting write-ups all over because, well, it’s a hip-hop track by Bob’s grandson. Otherwise, it would’ve never seen the light. The track’s a soulless anthem, excruciatingly bland, and Dylan’s flow is like a copy of Drake’s that has itself then been copied, fading with each reproduction. But the kid’s only 15, so for that age, it’s not bad at all. We’ll see.

What’s particularly interesting about the case of Pablo Dylan is he’s yet another entry into the world of rich kids of famous white people making hip-hop. Dylan joins Chet Haze, son of Tom Hanks, who made a tone-deaf remix of Wiz Khalifa’s “Black and Yellow” called “White and Purple”—which, by combining the colors of his college, Northwestern, and a reference to weed, was remarkably efficient at tapping into clichés. Blessedly, Chet’s remained silent since then. On an entirely different wavelength, there’s Rich Hil, son of Tommy Hilfiger, who just got signed to Warner Bros. from Swizz Beats’ label, his debut album to be produced entirely by hardcore street-rap’s favorite son, Lex Luger.

As a lyricist, Hil shows little ability or promise: he seems stuck on his lamentations, sloppily stringing together come-ons and druggy boasts. But aside from the rhymes, he actually has talent, displaying an impressive taste for warped, minimalist beats that, paired with his hoarse rasp of a voice, seem surprisingly menacing for a kid who grew up in Connecticut as the son of a fashion designer. Drugs have always been a reliable way for a rich kid to go aggro—the secret weapon of the suburbs, so to speak—and Hil’s created an effective aesthetic out of it, even if he still hasn’t made a strong stand-alone track. It helps that next to the other goofballs who pass for white rappers these days, guys like Mac Miller and Asher Roth, Hil looks even better, though he’s got a long way to go before he can match up with Yelawolf, who might represent a ceiling of sorts for Hil’s art.

With the egalitarianism brought to hip-hop by the Internet, it’s hard to imagine these three will be the last of their kind. And at the very least with Hil, you’ve got to give him credit. Being a celebrity offspring will help you get that initial burst of attention that the average guy might take years to earn, the phase that Dylan’s going through now, but people are going to be naturally inclined to not take you seriously, call you a poser, shriek about nepotism.

It’s hardly surprising that these kids have turned to hip-hop, though. Buoyed by guys like Kanye, Drake, and Rich Hil co-sign Kid Cudi, the rap game today puts a strong focus on fame, and who knows more about fame than the grandson of Bob Dylan or the son of Tommy Hilfiger, the sister of Ally Hilfiger, who was a sacrificial lamb of MTV? Hil says he learned from his sister having been made into a pariah, and so, reality TV aside, music might be the only other place you can go where your fame is not only an enabler but also the subject.

If we believe everything we read in the tabloids, as we should and shouldn’t, then we know that it’s built into the DNA of rich kids (all kids?) to rebel. And if we study psychotherapy and pay attention to literature, as we should and shouldn’t, we also know that this rebellion is often a desperate play for the attention of distant parents, even at the cost of their approval. Think about it: you’re born into a family where you’re constantly in the shadow of your dad or grandpa; knowing you need to be famous, what happens if you can’t do it the way that they did?

Writer’s sons have long tried to be writers themselves. Same with musicians. Both rarely attain much success. There are the exceptions, cases like Martin Amis and Jeff Buckley, Sofia Coppola and Rashida Jones, though when you get into film the discussion changes. But here comes this art with a low barrier to entry, that glorifies rebellion, that welcomes and quantifies traditional acts of disdain like drugs and sex; and best of all: it didn’t even exist when your dad was your age. This is your game, and you don’t have to worry about papa Tom Hanks or papa Tommy Hilfiger ever picking up a microphone and trying to rap. And what’s better than a construct in which you can explore and exploit all of your best vices, smoke weed and sleep around, and the patriarch’s actually proud of what you’ve done, because it’s music? It’s a win-win for father and son.

It’s weird these days, too. On Pablo Dylan’s Twitter, the last few messages on July 27 were between him and his girlfriend, talking about how much they loved each other, an exchange that couldn’t be more anathema to the dark-sunglasses mystique of 60s Dylan. But we’ve all got to find our own way, and that includes the grandsons of legends.