Were I trying to tell the story of soul music, or even black popular music as a whole, in the late 20th century, I might focus on the emblematic career of Betty Wright, who died on May 10 (of cancer, not COVID-19, apparently). Like many of the singers in the classic era of soul, she sang gospel as a child. Her records of the early 1970s moved from classic soul toward disco, a very early version of that development. Dissatisfied with record companies that tried to control her material and eventually stopped promoting her records, she founded Ms. B Records, one of the few such enterprises created by a black woman in the era. By the time the neo-soul revival arrived in the early 2000s, she was producing records and arranging vocals for various artists. Soon she was recording an album with the Roots, getting sampled by Beyoncé, appearing on tracks with Lil Wayne.

She should’ve been getting the Aretha or at least Mavis Staples treatment as a beloved and iconic American master, but instead she seemingly sank into the background hum, though she never stopped working. Her death, however, provides an occasion to revisit all the early albums and catch up on what happened after.

Born in 1953 in Miami as Bessie Norris, she was singing in her family's gospel group by the time she was a toddler, transitioning to soul by 12. She put out her first album, the delightful and under-heard soul classic My First Time Around in 1968 at the age of 15. As the title indicates she started to specialize in "he made me a woman," or "I am definitely old enough" songs; I wonder how her gospel parents felt about this. Actually, Wright wanted to rock, and sounded great on songs like Cry Like a Baby. The record yielded a minor hit in "Girls Can't Do What Guys Do" (sleep around), but the record revealed a whole soul operation in Miami that could compete with Memphis, Muscle Shoals, or Detroit in every respect: by the late-1960s the playing, writing, arranging, and production values at labels like TK and Alston, and under the tutelage of producers such as Willie Clarke and Clarence Reid, were as good as anyones.

Though she faded for a few years as a recording artist after the first LP, Wright was doing everything that helped eventually to define "the sound of Miami," including bringing her talented friends into the studio (such as the eventual disco king George McCrae) and singing and arranging backup vocals on a series of records.

Her second album, I Love the Way You Love (1972), is one of the best soul albums ever made. I hear every song as a classic: "Clean Up Woman" (her career song) certainly, but also "Pure Love," "All Your Kissin' Sho' Don't Make True Lovin'" (with a killer wah-wah guitar riff, a la Shaft), and so on. I wore out two copies on LP; I've still got them both. In a couple of my serious relationships, tracks from the album were "our song." I spent a chunk of the decade proselytizing for it; I was enamored of its incredibly juicy guitar (provided by Willie Hale, aka Little Beaver) and its updating of classic soul sounds along the lines being explored right then by Isaac Hayes and by the city of Philadelphia as a whole. Nile Rogers ripped that "Good Times" disco strum right from the Beaver, I believe.

I paid attention after that on and off, but by the 1980s Wright had disappeared from the charts, though I still pulled out I Love the Way You Love from time to time, on LP and then CD and then MP3. As I go back, trying to patch the holes, a number of her albums, including the great Danger High Voltage, which yielded several chart hits in the 1970s, are out of print in all media; I don't have the LP version anymore. At least Shoorah! Shoorah! is on YouTube. As I say, Wright just never got her due.

At any rate, she sounded great from the very outset: somewhere between the extreme power of Aretha and the light touch of Diana Ross. She can go whole songs just popping along delightedly, or suddenly give a gospel-style growl that begins deep down, or launch into the "whistle register," the highest range of which the human voice is capable. Over-tracked with herself or working with backup singers, the intricate exchanges or elaborate harmonies are always perfectly constructed. From birth to death, she never sang wrong for a moment.

Recording as a teenager, however, Wright may have been politically retrograde, soul's answer to Tammy Wynette. She struggled for some years to find a follow-up to "Clean Up Woman" ("the reason I know so much about her, is because she picked up a man of mine"), until it began to seem like a squad of service workers was coming for your husband. By the time she got through "Baby Sitter" to Secretary ("it's very ordinary/for the secretary/to take a man away from his wife"), she was playing it for comedy. In all these cases, she advised sisters to satisfy their men relentlessly, lest the guys get swept away by the staff, and she tends to blame women who lose their men for being insufficiently sexy. Then also, as I say, many songs are in the vain of: "Last night, you made me a woman," or "You think I'm too young, but I know how to please a man."

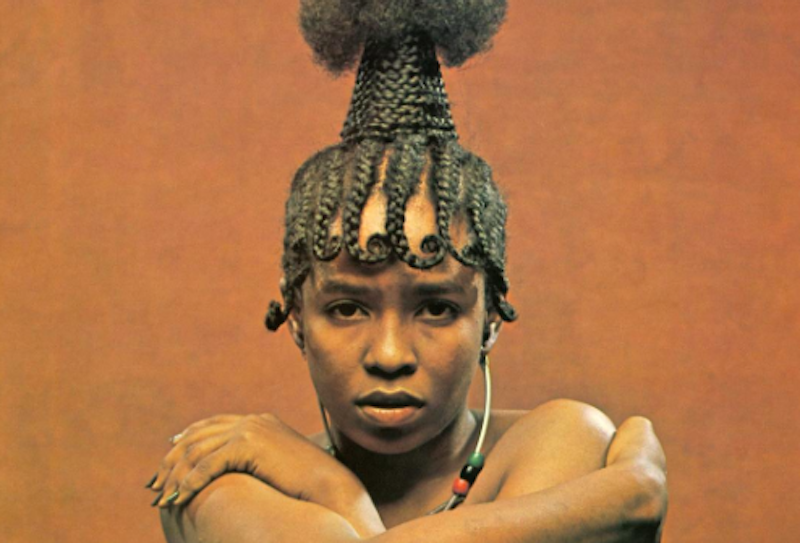

The lyrics on the first few albums would make good data if you were trying to elucidate the false consciousness induced by the patriarchy. The music is delightful, though. The lyrics have kitschy charm; and many artists (Taylor Swift, Avril Lavigne, and Bonnie Raitt for example) have explored the theme of feminine rivalry. By the mid-70s, though, Wright's processed hair had been replaced by Afrocentric braids and myriad "women be strong" songs, including even a cover of Helen Reddy's "I Am Woman" (surely the best version). But she held on to the sexy too, as in Let Me Be Your Lovemaker, one of the best and most stylistically forward-looking soul songs of the 70s, in which she shows the full vocal repertoire. "I know you don't think I'm ready/but open your eyes and see/As sure as my name is Betty/I can love away all your misery."

By the early-1980s, she’d faded as a fairly mild commercial force. This was the fate of many great soul artists, though some found commercial revivals in the period: such as Marvin Gaye with "Sexual Healing" or Aretha with 'Who's Zoomin' Who?" Wright had a few minor scores, as with a song Stevie Wonder penned for her ("What Are You Gonna Do With It?") which got her back on Soul Train, but isn’t even on iTunes. But she was completely in command of her own career, her own voice, and her own record company, and was contributing to music in Miami and elsewhere: arranging vocals for Gloria Estefan's records, for example.

The albums trickled out through the 2000s and 2010s, all worth listening to and all beautifully crafted. In 2004, at the leading edge of another soul revival, she co-produced and co-wrote British artist Joss Stone's album Mind, Body, and Soul, which is essentially a very fine Betty Wright album, sung by Stone, often in the style of Wright ("Spoiled," for example). The highlight of her late period, however, is Betty Wright: The Movie, her 2011 album with the Roots (as far as I can tell there’s no actual movie). They give her, and she gives them, a workout, and she can still hit the whistle register. I picture Questlove soaking up everything Wright had to teach about how to make soul music. The guitar throughout is a tribute to Little Beaver, and Wright sounds as at home and in command in '11 as she did in '74. Her politics deepened in the '10s, as in Dry Well, her song about police violence dedicated to her son Patrick, who was killed in 2005.

Wright’s career was surprisingly eclectic. She monologues like Shirley Caesar or Bill Anderson (check out her contribution to Richard "Dimples" Fields' "She's Got Papers on Me"). She's gut-bucket soul or quiet storm r&b a la Mary J. Blige (as on the excellent 2014 album Living Love Lies). She married Jamaican artist Noel "King Sporty" Williams and dipped into reggae. It's straightforward dance music (Slip and Do It ), or it's tear-jerkers verging on country, or it's sound of Miami with a Latin lilt in the rhythm, or the rhythm track is hip hop and Snoop Dogg is featuring. This makes it sound like she was willing to flow wherever the winds blew, in search of a hit. I feel otherwise: early in her career she anticipated what was coming next and I hear her as present at the center of American music at many moments. Betty Wright was fully herself and was an authentic zone of creativity throughout her cradle-to-grave career. Swan Song.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell