Before I became the person I am today, who obsessively and mechanically obeys every statute, I was a teenage shoplifter in the 1970s. I had to be, to keep up with my three brothers, who had the coolest and most obscure music in a variety of genres just before it was released. My broke approach was to head to Discount Books and Records over on Wisconsin Ave. in D.C. and see whether I could leave with a few of the oddest-looking new releases and imports. I had several scores, in the sense that I found stuff that my bros didn't know and that we all dug.

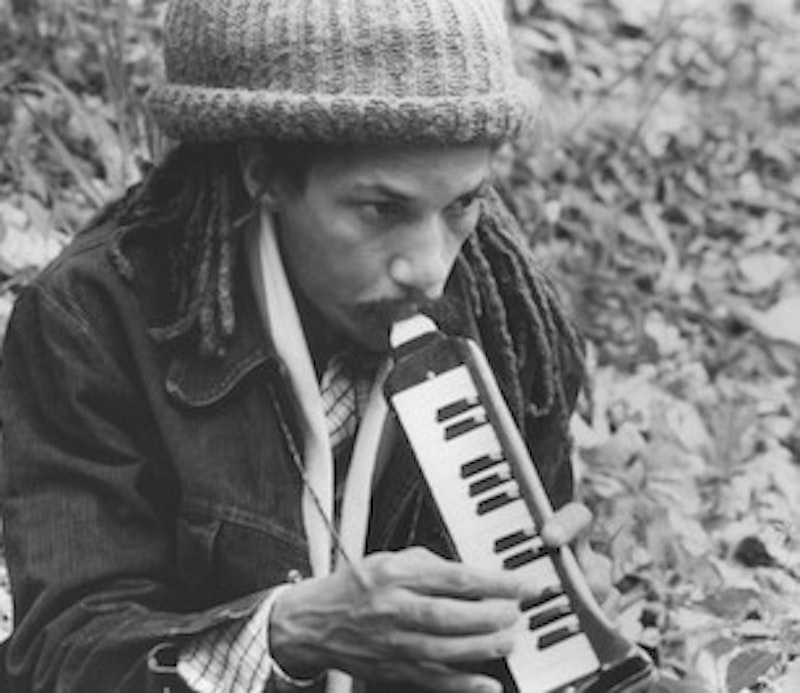

I lifted an album that I’ve been listening to on and off ever since: Augustus Pablo's East of the River Nile. The cover said, "Shoplift me," though I may have misinterpreted it. It pictured Pablo (Horace Swaby), a skinny Rastaman, sitting on a rock in the middle of a river (perhaps not the Nile, however; maybe it's the Black River in Jamaica), blowing on a melodica as though accompanying the water's flow. You've probably seen a melodica: it's Hohner's name for a wind instrument that uses a keyboard to sound harmonica reeds. Augustus Pablo might be the only person who ever made a living playing the melodica, and he put out album with the ironic title Melodica for Hire. Apparently they were used to teach music to schoolchildren in Kingston—as an American elementary school might use the recorder—and Pablo saw a girl playing one on the street and asked if he could take a crack.

He was already, at that point, a session keyboard player, closely aligned with the great rock steady organist Jackie Mittoo. But now he started releasing melodica instrumentals: deceptively simple, seemingly improvisational and meditative, often played in a minor key over previously-existing rock steady and early reggae tracks. The approach became known as "the far east style"; it was partly based, I think, on Jewish folk music, and often sounds like a sort of half-speed klezmer. In the 1970s, Pablo emerged as a producer and worked with many of the top singers and bands in Jamaica. Like a number of Jamaican producers, he started sending his records to the dub inventor, King Tubby, who remixed them variously.

By 1976, the two were working together closely, and issued one of the fundamental documents of dub music, King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown (Rockers was Pablo's record company, and his brother's sound system). The way Tubby and Pablo and others were thinking about making music then became a new template: they assembled tracks out of pre-recorded materials, and often made multiple “versions” of the same song: with or without vocals, or with and without melodica, dropping instruments and motifs in and out randomly, adding echo effects, suddenly starting and stopping midway through. Without this idea, you don't get to hip-hop, for example.

If you listen through the whole (vast) Pablo catalogue, you’ll hear a number of interpretations of the same riddim ("Satta Massagana," for example), and it’d be an art to trace each bass line to its source in Studio One rock steady tracks. Music suddenly became modular, something assembled in the studio rather than played through with a band. And yet Pablo improvised above the re-assembled tracks in a way that gave the recordings a particular coherent voice.

And it’s an extremely unusual voice. Pablo's recordings are wordless Rasta hymns. With a few exceptions, such as the hilarious "Bedroom Mazurka," Pablo made religious music of a particular intensity and humility. It's some of the most spiritual music ever recorded, though Pablo doesn't say a word. Even the Jewish references are used for serious spiritual and political purposes, and Rastas were at that point teaching a kind of Black Zionism, a return to the Promised Land, as were many of the songs Pablo worked over and re-assembled. In ways that might not strike you immediately, this stripped-down instrumental music conveyed all sorts of content.

Pablo's work is uniquely egoless, which is the essence of his spiritual message. The sound of the melodica itself is "naive," and shifts in timbre and tone are achieved by studio effects. But Pablo specifically tries not to show his virtuosity on the keyboard; he wanderingly follows the rhythm or cuts right to its essence, often very simply with a line of single notes or two-note semi-chords. It's not about himself; it's about the bass line, and about Jah Rastafari. He's the opposite, for example, of John Coltrane, and you come out thinking not "That's impossible!" but "I bet I could do that too." I've tried, but it's harder than it sounds to do it well.

As roots reggae was swamped in the 1980s by dancehall "slackness," Pablo just continued in the same vein, album after album of meditative instrumentals. I read a description once of Pablo and his crew in a studio in London; after a while the engineer couldn't see the musicians through the clouds of ganja smoke. There may be worse ideas than getting stoned and listening to a couple of hours of Pablo: either way, I'm liable to have it on in the background as I do almost anything; it takes up just as much of your attention as you want it to; it creates a contemplative mood. Pablo is probably the one artist I've actually listened to most, because the music works in almost any situation, no matter whom you're hanging out with, and it brings you toward peace with the universe.

Augustus Pablo died in 1999 of Myasthenia Gravis, but I occasionally hear that melodica wafting down out of the clouds.

Playlist: Really you could download 150 songs and just let Pablo play through your life. Or you could take these 20 cuts and make a playlist that has each of them three times: the point is the mood, not the cut.

"Chant to King Selassie I"

"Africa"

"King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown"

"Keep on Dubbing"

"Zion High"

"Pablo Satta"

"Slave Master's Execution"

"Pablo's Conference"

"Mr. Bassie"

"Vibrate On"

"Mountain View Dub"

"Far East"

"Addis-a-Baba"

"Bedroom Mazurka"

"Bedroom Mazurka (Version)"

"Satta Dub"

"Up Warrika Hill"

"Mountain View Dub"

"Sky Gazer"

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell