Pink Floyd was most interesting when it wasn’t sure what it was doing. I very much like the original incarnation of Floyd, when the band was guided by Syd Barrett's vision of psychedelia-for-more-than-half-cracked children. And I also enjoy the later Floyd, where the band was guided by Roger Waters' bloated and embarrassing concept album profundities. But I pledge my heart to those albums in the middle, where Waters and company were wandering from gimmick to gimmick in a stoned, hopeful daze, searching vaguely for commercial or artistic success, half pretending to be avant garde, half pretending to care about pop.

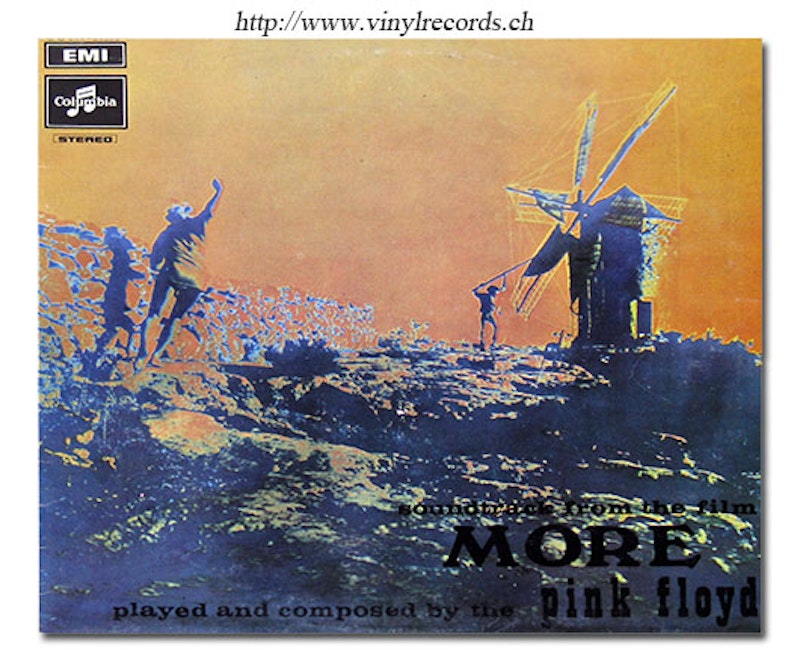

One of the best, and most scattered, albums from this mid-period is 1969’s soundtrack from the film More. It was the band's third album, and the first entirely made without Barrett, whose increasingly erratic behavior had prompted the band to jettison him. Waters had taken over much of the songwriting, and David Gilmour had moved in as guitarist and lead vocalist, but neither had established the style (or if you prefer, the rut) that defined them for the later 70s.

Admittedly, several songs do point ahead to Pink Floyd's languidly tuneful future. "Cirrus Minor" starts with meadow sounds and then Gilmour lazily sings about willow trees while plucking a Flamenco sounding guitar and Richard Wright's organ quivers profoundly before taking over the track. "Crying Song", "Green Is the Colour," and "Cymabline" all follow a similar blueprint, with slightly different details (electric guitar instead of organ on "Crying Song," piano and flute on "Green Is the Colour.")

Other parts of the album, though, wander off in unexpected directions. "Up the Khyber," for example, is a stomping, Middle-Eastern inflected slab of fusion, with drummer Nick Mason asserting, for perhaps the only time in Pink Floyd's career, that he can play funk, while Wright throws down percussive discordant keyboard figures. "Main Theme" harks back to the psychedelic space explorations on Pink Floyd's first two albums, but with Mason creating a stronger, Spanish-tinged rhythmic foundation, and the rest of the band making like Iberia is somewhere between Mars and Pluto. "Quicksilver" is seven minutes of clangs and squeaks and drifting drones—pleasant highbrow posturing. "More Blues," on the other hand, is an earnest blues instrumental (parody?), with Gilmour's guitar dripping emotion all over the pristine production, like Jimmy Page dropped in a cleanroom.

Perhaps the two most bizarre tracks on the album are "A Spanish Piece" and "The Nile Song." “A Spanish Piece" is one minute of Flamenco guitar, with Gilmour adopting a terrible Spanish accent to mutter lascivious come-ons in the background. Looking at the later day professional time-server that Gilmour would become, it's hard to believe he ever had a sense of humor, much less a brain. But this song remains as evidence that once, anyway, something was happening in there—the man sounds genuinely demented, sniffing and lisping and muttering about Tequila as if that has anything to do with Spain. For once it's Gilmour who gets to play the eccentric genius, rather than Barrett or Waters.

It's "The Nile Song," though, that is the highlight of the album, and possibly of Pink Floyd's entire career. It's built around a giant head-banging riff that sounds as if it's been dragged through granite. Off to the side, Nick Mason smashes away at the drums like the granddaddy of Dale Crover and Gilmour shouts incongruously about falling in love on the banks of the Nile. This was 1969, remember—Black Sabbath was barely up and slogging, and Deep Purple's Machine Head was still several years in the future. Yet here's mellow Pink Floyd with an honest-to-God slab of metal wedged in between dreamy odes to cloudbanks and faux Flamenco fusion. From track to track on More, you never know what you're going to get, which has made this one of Pink Floyd's least popular albums, and maybe its best.

Pink Floyd's Best Album Is Also One of Their Least Known

With Syd Barrett gone, the band reinvented itself.