It's taken me about 20 years to appreciate fIREHOSE’s Flyin’ the Flannel. A friend taped it for me back in the early 1990s, maybe a year or two after its release in 1991. I didn't hate it, and listened for a fair amount because my friend said I should like it. But it was only when I played it again last month after that two-decade hiatus that I ended up falling in love—and buying all of fIREHOSE's other albums.

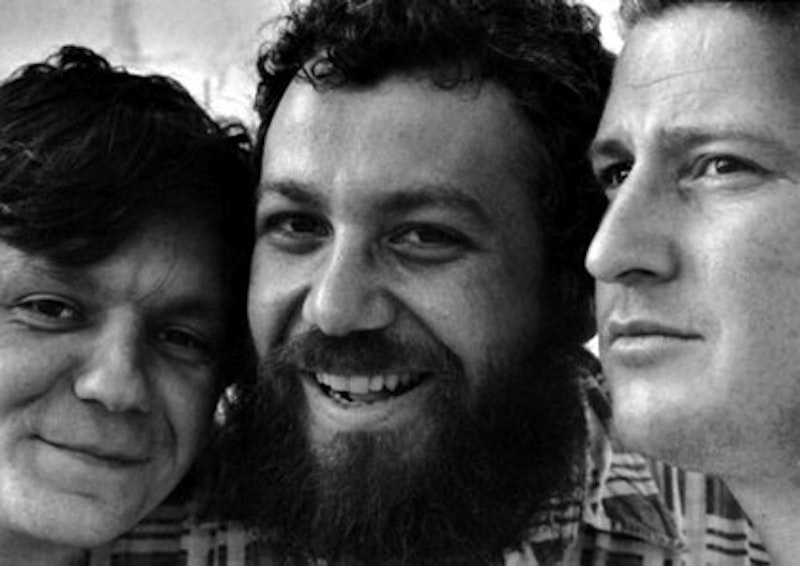

It's appropriate that I had to wait, and wait, to really appreciate the band. Most rock at least makes some pretense at aiming for the kids, but fIREHOSE really is music for aging decadents. Bassist Mike Watt and drummer George Hurley were already punk legends when the band coalesced—they'd been two thirds of the Minutemen, before guitarist D. Boon died. The new guitarist and vocalist, Ed Crawford, substituted for Boon's youthful political charge a jaded, wigged out irony—everything the band does sounds like it's in quotes. One of their songs, from 1993's Mr. Machinery Operator is even called "More Famous Quotes." Another, from 1987's If'n, is titled "For the Singer of REM" and is a gleefully goofy skewering of Michael Stipe, with Crawford burbling about how "the door’s a symbol for/these objects in your drawer," while Watt and Crawford somehow imitate REM's folk-rock shimmer exactly while still sounding like their own spiky, funky selves. It's as if they've contemptuously swallowed their target whole.

As that parody suggests, there's a little Weird Al in fIREHOSE's makeup, but it's Weird Al as he would have been if he were more musically talented and more ambitious than any of the bands he parodied. fIREHOSE is undoubtedly joking throughout Flyin' the Flannel, but the jokes are so fractured and bizarre and cool-as-shit that they end up slipping over into the sublime. It's the greatest chortling grandpa music ever.

Most of the songs on Flyin' the Flannel are only one-to-two minutes long, and they all seem put together out of spare pieces, shards, and novelty items. "Can't Believe" is a joyful power-pop ode to love into which someone has inadvertently dropped a barrel-full of amphetamines and the lunatic that swallowed them. Crawford wails his Michael Nesmith lines like Rob Halford with head trauma, while Watt and Hurley burp and stutter, turning the wannabe triumphant hook into a series of strutting pratfalls. On the band's version of Daniel Johnston's "Walking the Cow," Mike Watt emotes like a slowed down Elvis, while the band turns the fey original into a faux-soulful stroll, with the meaty bass insisting that there really is a cow lowing over there. "Flyin' the Flannel" is a cock rock roar about the need for tailors, interspersed with fruity folksy interludes, as Watt's base meditatively scuffles about in the underbrush. And then there's "Towin' the Line," which is maybe the album's closest song to actual funk. Though it's still all slowed down and spaced apart, like George Clinton leisurely bouncing around the studio on a pogo stick.

Talking about individual tracks is a little deceptive though. The songs tend to blur into each other, not because they all sound the same, but, again, because they're each so fragmented. The whole feels less like a whole than like an assemblage, stitched together out of Hurley's weird shifting beats, Watt's weird shifting bass runs, and Crawford's weird shifting riffs and wails. You end up with this tattered, limping thing, which keeps trying to rock and then gets tired and goes off to fart or sit down for a rest, or bellow at the kids on the lawn. Maybe I felt like it was bellowing at me once upon a time, I don't know. But whatever my problem was, I'm glad I finally got old enough to like music this distracted and crotchety and glorious.