Justin Bieber’s had an eventful 15 months that included egg throwing, car chases, potentially incriminating photos, and tussles with his limo driver. His behavior caused a stir, but it’s not surprising or original: it fits with a long pattern of extremely young, highly successful musicians clashing with the system that provides them with a livelihood. One of the first artists to engage in a wild, disruptive journey after teen success—albeit in a completely different media environment—was the late Alex Chilton, subject of a new biography by Holly George-Warren entitled A Man Called Destruction.

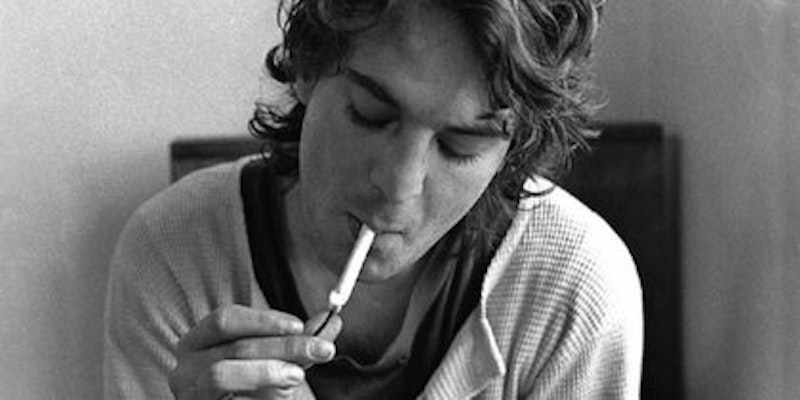

Chilton usually gets attention for two things: first, his work in the early-1970s rock band Big Star, which failed to hit big during their short career but acquired a large cult following over time; second, the inspiration he provided to the indie rockers of the 80s, most notably the Replacements, who recorded an ode to Chilton for their 1987 album Pleased To Meet Me. (More recently, a new compilation of solo Chilton material and a 1997 live recording have been released; Big Star was the subject of a documentary in 2013.) But Chilton sang lead vocals on “The Letter,” “the biggest hit single ever recorded in Memphis,” when he was just 16. The rest of his career was defined in opposition to his experience as a young star with a massive hit.

According to A Man Called Destruction, Chilton’s involvement in “The Letter” was almost accidental. Working at American Studios in Memphis, a songwriter and musician named Dan Penn—famous for writing soul hits like “Dark End Of The Street” and “I’m Your Puppet”—was looking to expand his portfolio. “I wanted to produce a hit record,” said Penn, “that was in my mind day and night.” He spoke to Chips Moman, who ran the studio, and told him, “I want to cut my own record, and I don’t even want you there. Find me somebody to cut around here.” So Moman went out and found him somebody—a local band named the Devilles that featured Chilton as the lead singer. Chilton hadn’t been in the band for long: he joined towards the end of 1966, less than a year before the Devilles recorded “The Letter.”

Penn added some bits to the demo with the help of session musicians known as the Memphis boys, who later played on famous recordings by Dusty Springfield and Elvis Presley. The single that Penn put together, clocking in at 1:58, may be one of the shortest #1 hits ever. That didn’t stop it from taking over Chilton’s life, though. A top hit means money, and an album containing that hit means a lot more money, whether you’re Chilton with “The Letter” or Pharrell with “Happy.” So the Devilles became the Box Tops, and Penn started working up an album. Chilton sang vocals; the tracks were all played by the session musicians. He had no control in this process, and “it rankled him that he had no say in the choice of the album’s songs.”

Chilton’s feeling of disillusionment only intensified. He described it as, “Here I am at the top, doing something I don’t understand and don’t really have any feeling for and getting really famous for it… it’s good to find that out when you’re young: Fame can make you money, but it’s a big pain in the ass. There are real advantages to being unknown.” A friend remembers a Box Tops show as “the girls screaming… and Alex looking bored to tears, going through the hits and hating it.” It wasn’t only friends who noticed the lead singer’s disengagement. Writing about another performance, Billboard noted that, “the Box Tops did their big sellers… but suffered from… lack of enthusiasm in their playing.”

The Box Tops eventually went bust, unable to stay relevant as pop music changed quickly at the end of the 60s. Chilton moved to Manhattan, playing shows alone and acoustic. He took one more shot at the mainstream with Big Star, but despite critical praise, the band never gained fame, largely due to some bad luck and nightmarish marketing. Stax distributed the first Big Star album, but as a label focused primarily on soul and funk, they didn't really know how to break a rock album.

A distribution deal that Al Bell, the head of Stax, set up with Clive Davis, the head of Columbia Records, at the end of 1972, promised better things, but then Davis was fired, which "totally scotched" the deal. “Columbia record executives did not like the terms Al Bell and Clive Davis negotiated… rather than distributing Stax’s product, CBS began warehousing the company’s releases,” to the detriment of Big Star and others. (In addition, Chris Bell was not really a member of the band by the time they started recording the second “Big Star” album.)

Chilton, increasingly dependent on drugs and alcohol, fought with his girlfriend—sometimes violently—and his bandmates. After an altercation with the Memphis police, he ended up in the hospital. He started using the studio to record at night. On one occasion, a fight in the control room left the valuable recording console covered in gin. In a later set of sessions, a friend of Chilton’s peed on the studio floor, alienating collaborators.

The tenor of the recording process can be seen in the reaction of famous Stax guitarist Steve Cropper, whose playing inspired everyone from the Beatles to Lou Reed to Chilton himself. Cropper “walked inside the door [to the studio], plugged his guitar in, and didn’t come any closer into that control room… He was freaked out.” Chilton had to be banned from the mixing process after recording, because the album “would never have been finished,” according to the producer Jim Dickinson.

The third and final Big Star album, put together mainly by Chilton and the drummer Jody Stephens, existed self-consciously out in the cold. Known as Third/Sister Lovers, this album turned out alternatively inspired and a total mess. It mostly avoided Chilton's previous work in Big Star, as well as anything that might end up on a radio.

Dickinson, who also worked on Chilton’s subsequent solo album, characterized the musician’s mindset as, “This is gonna be mine, so I’m gonna be the one who fucks it up.” This attitude stuck with Chilton the rest of his career. Forced to cede control as a teenager, he held on tight afterwards, rejoicing in the mistakes that Penn and the studio musicians had tried so hard to avoid on the clean, immaculate Box Tops recordings. Chilton worked to imbue his music with the disillusionment, tragedy, and violence he felt. Writing in Rolling Stone after the release of 1987’s High Priest, Michael Azerrad—whose 2001 book Our Band Could Be Your Life investigated seminal 80s indie bands, some of whom drew inspiration from Chilton—suggested that “Chilton can write great songs, but ‘ruins’ them with skranky guitars, sloppy takes or off-key singing.”

Chilton’s life-long efforts to avoid anything remotely successful are seen as a courageous artistic statement, a sign of uncompromising integrity. Of course, today a million-selling teen heartthrob in his mold would face intense scrutiny. Every musical attempt he made to escape his past would be picked apart and mocked. Every aspect of his life—the bar fights, the domestic disputes, the run-ins with the cops—would be huge news. He’d be a lot less like an indie rock icon, and a lot more like Justin Bieber.

—Follow Elias Leight on Twitter: @ehleight