What’s the best New Wave album ever? According to Paste, it’s Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True. NME’s unranked list includes Television’s Marquee Moon, Blondie’s Parallel Lines, and The Cars self-titled release. Louder lists Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense and New Order’s Power, Corruption and Lies.

These are all highly-regarded New Wave bands. They’re also all white.

Like classic rock and country music, New Wave is a very white genre. Some critics have argued that that’s because it is about whiteness. Philosopher of popular music Robin James, for example, claims that the herky-jerky rhythms, robotic vocals, and alienated lyrics all create a “musical disorientation [which] re-centers conventional accounts of whiteness, specifically, white (men’s) anxieties about their bodies.”

James isn’t necessarily wrong about the fetishization of white awkwardness in bands like Devo and Talking Heads. But New Wave isn’t just white because it takes whiteness as its subject matter. It’s white because the genre is defined by whiteness.

Critics sometimes treat genres as if they’re built entirely around form. You categorize Led Zeppelin as classic rock because they used electrified blues-based guitar licks; you categorize Nicki Minaj as hip-hop because she raps rather than sings. New Order is a New Wave band because they use stiff rhythms, mix rock with electronica, and sing lyrics about alienation, disjunction, and paranoia.

Genres aren’t just a matter of formal characteristics. They’re also defined through cultural or social markers. For example, New Wave is defined chronologically; it’s a movement of the late-1970s and early- to mid-80s. Performers who fall before or after that period might occasionally be described as New Wave, but they aren’t seen as central. That’s why New Order shows up on best-of New Wave lists, while Cut Copy—a similar band that showed up 20 years too late—generally doesn’t.

One of the major ways genres are defined in the US is through race. Early blues and rural music, in the 1920s and 1930s was split into race records—which featured Black performers—and hillbilly music—which featured white performers. There’s little formal difference between Mississippi John Hurt, the Allen Brothers, Jimmie Rodgers, and the Mississippi Sheiks. But the white performers (then and now) are country music, and the Black performers are blues.

There’s a similar dynamic at work in New Wave music. The pioneering Black female band ESG played sparse, repetitive herky-jerky funk while hypnotically declaring “You make no/You make no/You make no sense.” They sound like a more bass-heavy, stripped-down Devo. But while they’re often credited as formative influences on house and hip-hop, they’re rarely discussed as New Wave performers.

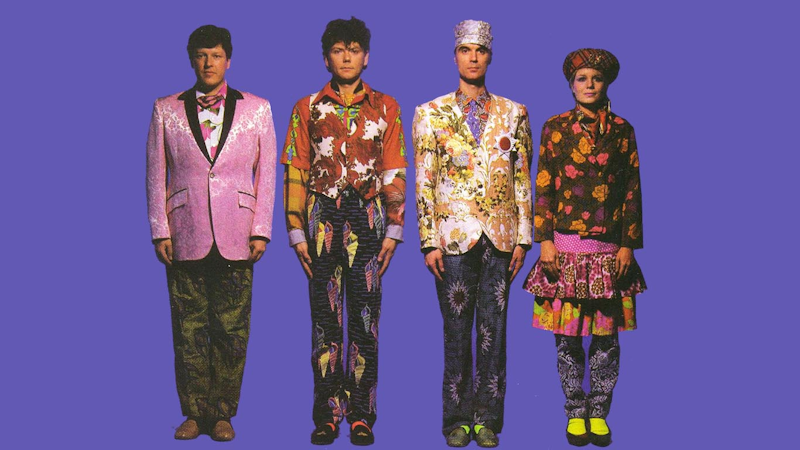

ESG isn’t an isolated case. There are lots of Black performers from the period that sound New Wave and are obviously in conversation with New Wave artists. Ice queen Grace Jones had the robot alien act down better than any white would-be android, and even covered songs by white New Wave bands like the Pretenders and the Normal. New Wave goddess Debbie Harry name-checks Grandmaster Flash—so why isn’t Grandmaster Flash, or early hip-hop electro funk from Run-D.M.C., Herbie Hancock, or Afrika Bambaataa considered part of that same pantheon? Prince’s “Controversy” and Janet Jackson’s “Nasty Girl” are as tightly wound as any New Wave performance—and their eccentric synth rock is a lot newer and more forward-looking than Elvis Costello’s straightforward singer/songwriter guitar songs.

Genre boundaries are flexible, and New Wave doesn’t completely exclude Black performers. Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex is often categorized as New Wave; so are Grace Jones and Prince on occasion. But they’re rarely, if ever, seen as central to the genre. If Prince was really seriously considered a New Wave artist, Controversy or Purple Rain would consistently be in the top five on all those best of lists. ESG, Grace Jones and Janet Jackson would pop up as well. And what about Yellow Magic Orchestra?

Prince isn’t an underrated or unknown artist. Janet Jackson arguably doesn’t get enough respect, but she’s sold a lot of units. Black performers can be successful and critically acclaimed without being New Wave artists. So why does it matter that Black people are defined out of the genre?

I think it matters because it warps our sense of history. New Wave in most popular accounts is a segregated movement. But it was only segregated because Black people who made New Wave music were called something other than New Wave by critics. If we want to understand what was happening in the pop culture of the period, we need to recognize how racial dynamics influence the stories we tell.

Those stories aren’t just racial; they’re racist. New Wave, like the name says, was a genre that was celebrated for its innovation and its oddness. It’s often framed as an edgy rebellion against a conformist pop culture. So, when white people are the only ones in that New Wave, it means that white people are the real innovators, the real rebels, and the real weirdos. Andrew Sullivan and Quillette embrace the same logic when they declare themselves brave contrarians for arguing that Black people have lower IQs.

There’s nothing rebellious, innovative, or anti-establishment about denigrating or excluding Black people. Racism is old. New Wave is too, at this point. But New Wave looks a lot less moribund when we stop pretending the strange alienated robot future was ever the exclusive preserve of white people.